About Little Gidding

Around 1625, an elderly Mary Ferrar purchased the rundown manor at Little Gidding, about 30 miles outside of Cambridge in England. Shortly after, she and her unmarried adult son Nicholas moved there to begin cleaning it up. Soliciting help from family members — including Nicholas’s brother John, his sister Susanna, and their large, growing families — they had, by 1630, transformed the manor into an experiment in intentional living: Little Gidding.

The popular image of Little Gidding, derived from nineteenth-century hagiographies of the saintly patriarch Nicholas and reinforced by T. S. Eliot’s famous poem, “Little Gidding,” depicts it as a place of religious retirement and regimented devotion. Family members recited from the Bible at appointed hours throughout the day, dividing it such that they read the entire Psalter every month and the books of the four evangelists three times a year. They compiled a hymnal and sang together in the morning and evening, clustered around an organ installed in their home for this purpose. Nicholas Ferrar also gathered histories and excerpts from books like John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs for the children to read aloud during meals; in this way, they practiced their elocution while edifying the family. Psalms were especially important at Little Gidding, and the family supplied neighboring children in the parish with a Psalter, offering a penny to each “psalm-child,” as they were called, who could recite passages from memory on Sunday mornings. Everyone wore simple clothing, and two of the older daughters, Mary Collet and Anna Collet, pledged themselves to a life of celibacy. By committing themselves every hour of every day to holy work and worship, the extended Ferrar family invented a kind of High Anglican monastery, where service to family and community blended seamlessly with the worship of God.

Yet there is another side to Little Gidding. Forasmuch as the Ferrar family wanted to live a private life of rural retirement, they also wanted to advertise their own brand of Anglican devotion to a broader public. Or, as Nicholas Ferrar famously put it, in an oft-repeated quote, they sought to be “a pattern for an adge [sic] that needs patterns.” Throughout the 1630s, this scheme manifests most obviously in the Little Gidding harmonies and concordances, the subject of this digital project.

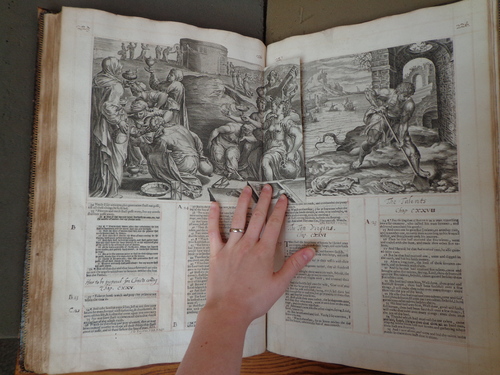

The harmonies and concordances, known collectively for simplicity’s sake as the “Little Gidding harmonies,” are large, often lavish manuscript volumes composed of high-quality, thick paper. On these sheets are pasted fragments of text cut from Bibles as well as religious prints, sometimes with individual figures sliced out and arranged into elaborate visual collages. Rolling presses were used to flatten each sheet before binding, and extra headings were often made from loose pieces of type used to stamp the paper. In this way, although they are made from the pieces of other books, the harmonies are so carefully glued together so as to look printed, and in fact Nicholas’s brother John later described their method of composition as “a new kind of printing.”

The women of the community were primarily responsible for making these books. Every weekday afternoon, in a special green chamber known as the Concordance Room, the Collet sisters might be found remixing printed materials, ruling the finished sheets, or binding them in gold-tooled leather or velvet covers. This labor was part of their devotional practice, a way of putting women’s hands and domestic skills with scissors and needle to work; but it was also a means of promoting Little Gidding to powerful patrons. The household made harmonies for King Charles, Archbishop William Laud, and Charles’s son Prince Charles, as well as for their friends, like the poet George Herbert. While they did not exactly “sell” the harmonies, their placement in the highest households in England secured the community’s safety, promoted their vision of Anglicanism, and ensured that their private modes of living would have an impact on public life.

To learn more about individual harmonies, please read the introductions to each edition. Starting with the Houghton gospel harmony of 1630 and moving through chronologically to the Pentateuch concordance of 1642 will give you a good sense of the development of Little Gidding’s unique “new kind of printing.” A fuller argument about the harmonies as proto-feminist technologies can be found in the chapter accompanying this website, “Cut: Little Gidding’s Feminist Printing,” in Cut/Copy/Paste: Fragments from the History of Bookwork (2021). Readers may also wish to consult the articles and books below, which offer crucial background on Little Gidding as well as arguments about the harmonies and their place in contemporary book and literary history.

Further Reading

The scholar Paul Dyck has done much work on George Herbert and Little Gidding. He has also produced an incredible, fully marked-up edition of the King’s Harmony, available here. Dyck's articles include:

- “‘So rare a use’: Scissors, Reading, and Devotion at Little Gidding,” George Herbert Journal 27, no. 1/2 (2003/2004): 67–81.

- “‘A New Kind of Printing’: Cutting and Pasting a Book for a King at Little Gidding,” The Library 9, no. 3 (2008): 306–33.

- “The Discovery of Pattern at Little Gidding,” in Women’s Bookscapes in Early Modern Britain, eds. Leah Knight, Micheline White, and Elizabeth Sauer (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2018), 135–52.

The art historian Michael Gaudio has written the first full-length book on the harmonies: The Bible and the Printed Image in Early Modern England: Little Gidding and the Pursuit of Scriptural Harmony (New York: Routledge, 2016). Joyce Ransome has written an updated biography of Nicholas Ferrar and the community: Web of Friendship: Nicholas Ferrar and Little Gidding (Cambridge: James Clark, 2011). Both are indispensable resources.

Adam Smyth has been studying the harmonies from the angle of book history and early modern material culture, in ways that deeply inform the goals of this digital project. He discusses Little Gidding in:

- “‘Shreds of holinesse’: George Herbert, Little Gidding, and Cutting Up Texts in Early Modern England,” English Literary Renaissance 9 (2012): 452–81.

- “Little Clippings: Cutting and Pasting Bibles in the 1630s,” Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 43, no. 3 (2015): 595–613.

- Chapter 1, Material Texts in Early Modern England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018).

Other recent articles on Little Gidding and its work include:

- Patricia Badir, “Fixing Affections: Nicholas and John Ferrar and the Books of Little Gidding,” English Literary Renaissance 49, no. 3 (2019): 390–422.

- Paul A. Parrish,“Richard Crashaw, Mary Collet, and the ‘Arminian Nunnery’ of Little Gidding,” in Representing Women in Renaissance England, ed. Claude J. Summers and Ted-Larry Pebworth (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1997), 187–200.

- David Ransome, “Little Gidding and the Eikon Basilike of King Charles I,” Transactions of the Cambridge Bibliographical Society 16, no. 3 (2018): 401–14.

- Debora Shuger, “Laudian Feminism and the Household Republic of Little Gidding,” JMEMS 44, no. 1 (2014): 69–94.

Most of our information about the household's modes of living are derived from John Ferrar's materials toward writing a life of his brother Nicholas. They have been heavily edited over the years; the modern edition is Materials for the Life of Nicholas Ferrar: A Reconstruction of John Ferrar’s Account of His Brother’s Life Based on All the Surviving Copies, ed. Lynette R. Muir and John A. White (Leeds, England: Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society, 2006). Badir discusses making of this book in her article, listed above. Further information can be found in the letters and leftover cut prints in the Ferrar Papers at Magdalene College, Cambridge, edited by David Ransome; digitized microfilm images are available (behind a paywall) through the Virginia Company Archives published by Adam Matthew Digital.