William Penn's 1683 Letter to the Free Society of Traders: Difference between revisions

(Created page with "=== Introduction ===") |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

=== | ==Overview== | ||

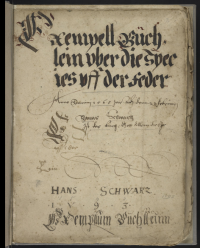

This is a manuscript collection of miscellaneous writings from a German man named Hans Schwartz (also known as Hanns Schwartz) that can be found at the Kislak Center for Special Collections at the University of Pennsylvania[https://www.library.upenn.edu/kislak]. It was written in the mid-to-late 1500s as noted by two dates on one of the introductory pages-1r (1568 and 1593). There are 11 “works” or different entries followed by four business entries about payments and purchases. It's a manuscript that appears to be the personal journal of Hans Schwartz that he kept for more than 20 years.[[File:Introductory_pages.png|thumb|200px|Introductory Pages]] | |||

==Historical Context== | |||

===William Penn's Life as Proprietor of the Pennsylvania Colony=== | |||

The author of this letter was William Penn (1644-1718), the founder of the Pennsylvania colony. The colony was named Pennsylvania to commemorate Penn’s father, Admiral Sir William Penn. William Penn was granted this swath of land by King Charles II of England in 1681 as a debt repayment that the Crown owed Penn’s father. In 1682, when William Penn ventured to the Pennsylvania colony for the first time, the colonists swore their loyalty to him as the proprietor of the Pennsylvania colony. As proprietor, Penn wielded a royally sanctioned power to manage the colony and becomes its governor. | |||

===William Penn's Relationship with Native Americans=== | |||

[[File:toomuchtoknow.jpg|thumb|200px|Too Much To Know: Ann Blair]] | |||

Penn was a philosopher in the dichotomy of conflict versus peace. He belonged to the Religious Society of Friends (the Quakers), a sect of Protestant Christianity whose focus was on applying peaceful practices to every facet of one’s life. His progressive approach to dealing with conflict by de-escalation and compromise was illustrated by the cordial relations he developed with the Lenape Native American people. | |||

William Penn’s peaceful practices with native American tribes paid off economically, as he was able to learn more about their practices and assimilate within their economic activity. In his 1683 letter, Penn includes a great deal of information “[o]f the Natives or Aborigines, their Language, Customs and Manners, Diet, Houses or Wigmans, Liberality, casie way of Living, Physick, Burial, Religion, Sacrifices and Cantico, Festivals, Government, and their order in Council upon Treaties for Land, and their Justice upon Evil Doers,” as written in the frontispiece. By practicing peace with the native Americans in and surrounding his colony, Penn was able to gain insight into the nuanced facets of their lives, which could only more difficulty be achieved if he was not amicable with the natives. | |||

===Publisher of the Letter: The Stationers' Company=== | |||

[[File:war_1.jpeg|thumb|200px|Peasant War of 1525]] | |||

The publisher of this letter was Andrew Sowle, a member of the Stationers' Company. The Stationers’ Company in London was a royally-sanctioned organization that was given all-encompassing power over the printing of all works in Britain. The Stationers’ Company held a monopoly over the printing industry, controlling and owning the rights to every printed work in Britain. Therefore, although William Penn wrote this letter, Sowle and the Stationers’ Company owned the rights to this letter and could publish it as they pleased. Understanding the publisher of this letter and the contemporary British publication landscape provides greater insight into understanding William Penn’s 1683 letter. | |||

To provide more background on the publication of this letter, a detailed dive into the Stationers’ Company is needed. The Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers—the complete name for the Stationers’ Company—was one of the Livery Companies. The Livery Companies were a series of trade associations in the City of London that provided representation for certain industries, job, and/or trades. The Stationers’ Company was originally founded in the 14th century; in 1403, the Mayor of London approved the assembly of a Guild of Stationers, whose members were booksellers, bookbinders, text writers, illuminators, and suppliers of parchment, pens, and paper. Thus, the Company at last offered membership to all trades involved in the printing industry. This critical moment set the stage for how the Company tenuously monopolized the printing industry. | |||

In 1476, when the invention of printing arrived in England, printers joined the Company. In 1557, the Company received a Royal Charter of incorporation, bestowing the company with the power to restrict and control printing. Outside competition could no longer exist. | |||

Because William Penn’s letter was written in 1683 and printed in London, the only possible publishing logically would have been the Stationers’ Company. This suspicion was confirmed by curator John Pollack, who accessed further information on the letter and confirmed that, in fact, Andrew Sowle was a member of the Stationers’ Company. | |||

Understanding the Stationers’ Company is important to contextualize the landscape of how William Penn’s 1683 letter was published. | |||

==Analysis of the Letter== | |||

===Purpose of the Letter=== | |||

The purpose of writing this letter was for William Penn to provide an update on the economic and sociopolitical landscape of his colony, particularly his flagship city Philadelphia. By providing this update, Penn wanted to encourage his group of investors to provide funding and grassroots growth for the burgeoning economy of the Pennsylvania colony. Essentially, this letter had an advertising goal. Capitalism was the driving force for writing this letter. | |||

The first page of the letter is a frontispiece, which clearly states the content of the letter, the purpose of the letter, and whom the letter is addressed to. The frontispiece describes that the letter’s intent is to provide detailed information about the city of Philadelphia, specifically its economic and sociopolitical circumstances. According to the frontispiece, this letter was written to the Free Society of Traders in London—a company of businessmen, landowners, and associates of William Penn, who were given special power by Penn to direct the economic activity of the young American colony. Based on the content and intended audience of this letter, the letter was made for the purpose of informing William Penn’s investors about the current situation of the colonies, so that they could make informed decisions about future plans and directions for colonial economic activity. Writing this letter would allow him to garner support and money from wealthy people to further his colonial initiatives. | |||

The Free Society of Traders | |||

===Material Analysis=== | |||

A new binding was incorporated around the letter, made out of a red leather-like material. The purpose of the new binding was to preserve the integrity of the original papers. The spine of the new binding read “Letter from William Penn. 1683,” which clearly states the title, author, and publication year to make the work easily identifiable. The spine of the binding appears new, with some wear at the corners. The spine has elevated areas near both of the corners on both sides, which could be intended to counter potential damage. Clearly, this hardback, sturdy binding was designed to preserve the integrity of its valuable inner contents. | |||

The quality of the paper was an integral component of this 1683 letter. There are two sets of paper: one set that constitutes the new binding, and the other set being the original papers of William Penn’s letter. The paper from the new binding appears to have slightly yellowed and darkened, indicating natural wear and aging. This paper also appears to have slight striations/chain lines in the vertical direction. Under magnification, hair-like protrusions appear to come out of the paper; all of these clues can help me deduce the type of paper used. On the other hand, the original papers of William Penn’s letter are very stained and have lots of ink smears, perhaps from several users fingering through countless times. The type of ink used to make this letter was perhaps prone to smearing. The ink bled through very visibly between the recto and verso sides of the page, indicating that either the paper is very thin, the ink is very dense, or a synergism of both factors. The original papers are yellowed and darkened, and they seem to consist of old rags and linens, based on the amorphous structure of the paper. | |||

The formatting of the pages of this letter also hold significance. The dimensions of each page in the original letter are 11.25 inches in height and 7 inches in width, which point to the pages being in the gathering format of folio. Rather than page numbers, the bottom of each page is marked with a signature mark. For example, the first page of content has the signature “A2.” Each side of each page can be described as either “recto” or “verso,” with the former describing the front side of the page on the right side of the book, and the latter describing the back side of the page on the left side of the book. | |||

Marginalia is also an important component of this piece. There is a lot of marginalia written on the inside of the new binding. One of these bits describes an appraisal of the book’s value ($12,000) before the Kislak Center acquired it. | |||

A miscellaneous but critical element of the text is that long “S”’s are present! This element signifies the writing and printing traditions in Britain at the time, which include this additional formality that is not present in modern English language printing. Thus, the “s”’s and “f”’s are easy to confuse between each other when reading William Penn’s letter. | |||

Revision as of 18:53, 4 May 2022

Overview

This is a manuscript collection of miscellaneous writings from a German man named Hans Schwartz (also known as Hanns Schwartz) that can be found at the Kislak Center for Special Collections at the University of Pennsylvania[1]. It was written in the mid-to-late 1500s as noted by two dates on one of the introductory pages-1r (1568 and 1593). There are 11 “works” or different entries followed by four business entries about payments and purchases. It's a manuscript that appears to be the personal journal of Hans Schwartz that he kept for more than 20 years.

Historical Context

William Penn's Life as Proprietor of the Pennsylvania Colony

The author of this letter was William Penn (1644-1718), the founder of the Pennsylvania colony. The colony was named Pennsylvania to commemorate Penn’s father, Admiral Sir William Penn. William Penn was granted this swath of land by King Charles II of England in 1681 as a debt repayment that the Crown owed Penn’s father. In 1682, when William Penn ventured to the Pennsylvania colony for the first time, the colonists swore their loyalty to him as the proprietor of the Pennsylvania colony. As proprietor, Penn wielded a royally sanctioned power to manage the colony and becomes its governor.

William Penn's Relationship with Native Americans

Penn was a philosopher in the dichotomy of conflict versus peace. He belonged to the Religious Society of Friends (the Quakers), a sect of Protestant Christianity whose focus was on applying peaceful practices to every facet of one’s life. His progressive approach to dealing with conflict by de-escalation and compromise was illustrated by the cordial relations he developed with the Lenape Native American people.

William Penn’s peaceful practices with native American tribes paid off economically, as he was able to learn more about their practices and assimilate within their economic activity. In his 1683 letter, Penn includes a great deal of information “[o]f the Natives or Aborigines, their Language, Customs and Manners, Diet, Houses or Wigmans, Liberality, casie way of Living, Physick, Burial, Religion, Sacrifices and Cantico, Festivals, Government, and their order in Council upon Treaties for Land, and their Justice upon Evil Doers,” as written in the frontispiece. By practicing peace with the native Americans in and surrounding his colony, Penn was able to gain insight into the nuanced facets of their lives, which could only more difficulty be achieved if he was not amicable with the natives.

Publisher of the Letter: The Stationers' Company

The publisher of this letter was Andrew Sowle, a member of the Stationers' Company. The Stationers’ Company in London was a royally-sanctioned organization that was given all-encompassing power over the printing of all works in Britain. The Stationers’ Company held a monopoly over the printing industry, controlling and owning the rights to every printed work in Britain. Therefore, although William Penn wrote this letter, Sowle and the Stationers’ Company owned the rights to this letter and could publish it as they pleased. Understanding the publisher of this letter and the contemporary British publication landscape provides greater insight into understanding William Penn’s 1683 letter.

To provide more background on the publication of this letter, a detailed dive into the Stationers’ Company is needed. The Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers—the complete name for the Stationers’ Company—was one of the Livery Companies. The Livery Companies were a series of trade associations in the City of London that provided representation for certain industries, job, and/or trades. The Stationers’ Company was originally founded in the 14th century; in 1403, the Mayor of London approved the assembly of a Guild of Stationers, whose members were booksellers, bookbinders, text writers, illuminators, and suppliers of parchment, pens, and paper. Thus, the Company at last offered membership to all trades involved in the printing industry. This critical moment set the stage for how the Company tenuously monopolized the printing industry.

In 1476, when the invention of printing arrived in England, printers joined the Company. In 1557, the Company received a Royal Charter of incorporation, bestowing the company with the power to restrict and control printing. Outside competition could no longer exist.

Because William Penn’s letter was written in 1683 and printed in London, the only possible publishing logically would have been the Stationers’ Company. This suspicion was confirmed by curator John Pollack, who accessed further information on the letter and confirmed that, in fact, Andrew Sowle was a member of the Stationers’ Company.

Understanding the Stationers’ Company is important to contextualize the landscape of how William Penn’s 1683 letter was published.

Analysis of the Letter

Purpose of the Letter

The purpose of writing this letter was for William Penn to provide an update on the economic and sociopolitical landscape of his colony, particularly his flagship city Philadelphia. By providing this update, Penn wanted to encourage his group of investors to provide funding and grassroots growth for the burgeoning economy of the Pennsylvania colony. Essentially, this letter had an advertising goal. Capitalism was the driving force for writing this letter.

The first page of the letter is a frontispiece, which clearly states the content of the letter, the purpose of the letter, and whom the letter is addressed to. The frontispiece describes that the letter’s intent is to provide detailed information about the city of Philadelphia, specifically its economic and sociopolitical circumstances. According to the frontispiece, this letter was written to the Free Society of Traders in London—a company of businessmen, landowners, and associates of William Penn, who were given special power by Penn to direct the economic activity of the young American colony. Based on the content and intended audience of this letter, the letter was made for the purpose of informing William Penn’s investors about the current situation of the colonies, so that they could make informed decisions about future plans and directions for colonial economic activity. Writing this letter would allow him to garner support and money from wealthy people to further his colonial initiatives.

The Free Society of Traders

Material Analysis

A new binding was incorporated around the letter, made out of a red leather-like material. The purpose of the new binding was to preserve the integrity of the original papers. The spine of the new binding read “Letter from William Penn. 1683,” which clearly states the title, author, and publication year to make the work easily identifiable. The spine of the binding appears new, with some wear at the corners. The spine has elevated areas near both of the corners on both sides, which could be intended to counter potential damage. Clearly, this hardback, sturdy binding was designed to preserve the integrity of its valuable inner contents.

The quality of the paper was an integral component of this 1683 letter. There are two sets of paper: one set that constitutes the new binding, and the other set being the original papers of William Penn’s letter. The paper from the new binding appears to have slightly yellowed and darkened, indicating natural wear and aging. This paper also appears to have slight striations/chain lines in the vertical direction. Under magnification, hair-like protrusions appear to come out of the paper; all of these clues can help me deduce the type of paper used. On the other hand, the original papers of William Penn’s letter are very stained and have lots of ink smears, perhaps from several users fingering through countless times. The type of ink used to make this letter was perhaps prone to smearing. The ink bled through very visibly between the recto and verso sides of the page, indicating that either the paper is very thin, the ink is very dense, or a synergism of both factors. The original papers are yellowed and darkened, and they seem to consist of old rags and linens, based on the amorphous structure of the paper.

The formatting of the pages of this letter also hold significance. The dimensions of each page in the original letter are 11.25 inches in height and 7 inches in width, which point to the pages being in the gathering format of folio. Rather than page numbers, the bottom of each page is marked with a signature mark. For example, the first page of content has the signature “A2.” Each side of each page can be described as either “recto” or “verso,” with the former describing the front side of the page on the right side of the book, and the latter describing the back side of the page on the left side of the book.

Marginalia is also an important component of this piece. There is a lot of marginalia written on the inside of the new binding. One of these bits describes an appraisal of the book’s value ($12,000) before the Kislak Center acquired it.

A miscellaneous but critical element of the text is that long “S”’s are present! This element signifies the writing and printing traditions in Britain at the time, which include this additional formality that is not present in modern English language printing. Thus, the “s”’s and “f”’s are easy to confuse between each other when reading William Penn’s letter.