William Penn's 1683 Letter to the Free Society of Traders

Overview

William Penn was the governor and proprietor of the Pennsylvania Colony in the late 17th century. He was gifted this colony by the current King of England under his father’s namesake, Admiral Penn. [1] William Penn, in the nascent stages of his developing colony, sought to scout resources and potential for economic development. In 1683, after developing relationships with the local native Americans and gaining a geographic understanding of the city of Philadelphia, he drafted a letter to the Free Society of Traders. This Society comprised of investors whom Penn wanted to inform on the potential for economic growth in Pennsylvania so that he could accrue capital to further economic development. [2] Through exploring Penn himself, the Free Society of Traders, the Stationers' Company that published this letter, and the content and material of this letter, it can be deduced that the grand purpose of this letter was rooted in a capitalistic incentive to further English colonization in North America. A key element of the letter is a detailed map of Philadelphia, laid out by the local surveyor general, to inform readers on the geography of William Penn’s flagship city.

Purpose of the Letter

The purpose of writing this letter was for William Penn to provide an update on the economic and sociopolitical landscape of his colony, particularly his flagship city Philadelphia. [3] By providing this update, Penn wanted to encourage his group of investors to provide funding and grassroots growth for the burgeoning economy of the Pennsylvania colony. Essentially, this letter had an advertising goal. Capitalism was the driving force for writing this letter.

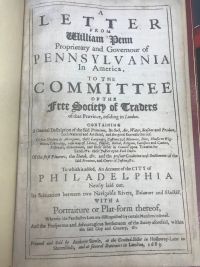

The first page of the letter is a frontispiece, which clearly states the content of the letter, the purpose of the letter, and to whom the letter is addressed. The frontispiece describes that the letter was written to the Free Society of Traders in London—a company of businessmen, landowners, and associates of William Penn, who were given special power by Penn to direct the economic activity of the young American colony. [2] Based on the content and intended audience of this letter, the letter was made for the purpose of informing William Penn’s investors about the current situation of the colonies, so that they could make informed decisions about future plans and directions for colonial economic activity. Writing this letter allowed him to garner support and money from wealthy people to further his colonial initiatives.

Historical Context

William Penn's Life as Proprietor of the Pennsylvania Colony

The author of this letter was William Penn (1644-1718), the founder of the Pennsylvania colony. The colony was named Pennsylvania to commemorate Penn’s father, Admiral Sir William Penn. William Penn was granted this swath of land by King Charles II of England in 1681 as a debt repayment that the Crown owed Penn’s father. In 1682, when William Penn ventured to the Pennsylvania colony for the first time, the colonists swore their loyalty to him as the proprietor of the Pennsylvania colony. As proprietor, Penn wielded a royally sanctioned power to manage the colony and becomes its governor. [1]

William Penn's Relationship with Native Americans

Penn was a philosopher in the dichotomy of conflict versus peace. He belonged to the Religious Society of Friends (the Quakers), a sect of Protestant Christianity whose focus was applying peaceful practices to every facet of one’s life. [1] His progressive approach to dealing with conflict by de-escalation and compromise was illustrated by the cordial relations he developed with the Lenape Native American people.

William Penn’s peaceful practices with native American tribes paid off economically, as he was able to learn more about their practices and assimilate within their economic activity. [1] In his 1683 letter, Penn includes a great deal of information “[o]f the Natives or Aborigines, their Language, Customs and Manners, Diet, Houses or Wigmans, Liberality, casie way of Living, Physick, Burial, Religion, Sacrifices and Cantico, Festivals, Government, and their order in Council upon Treaties for Land, and their Justice upon Evil Doers,” as written in the frontispiece. By practicing peace with the native Americans in and surrounding his colony, Penn was able to gain insight into the nuanced facets of their lives, which would be achieved more difficulty if he was not amicable with them.

Penn’s peaceful approach to life allowed him to gain further economic insight into his own colony, allowing him to garner monetary support from his investors (further discussed in this article) to grow the colony economically.

Recipients of the Letter: The Free Society of Traders

The Free Society of Traders was originally a joint-stock company, in which each member owned a certain proportion of stock depending on how much money they invested into the company. It originally launched in 1681, the same year that William Penn received the charter for the Pennsylvania colony from King Charles II. The Society was dedicated to spurring the economic growth of Penn’s colony, grounded in their trust in him to make the colony wealthy by utilizing its resources. To appeal to his investors, Penn gave each member of the Society a large portion of land in Pennsylvania and exclusive property rights in Philadelphia [3]—the city that Penn included a map of at the end of his 1683 letter. [2]

Publisher of the Letter: The Stationers' Company

Andrew Sowle

The publisher of this letter was Andrew Sowle, a member of the Stationers' Company. The Stationers' Company in London was a royally-sanctioned organization that was given all-encompassing power over the printing of all works in Britain. The Stationers' Company held a monopoly over the printing industry, controlling and owning the rights to every printed work in Britain. [4] Therefore, although William Penn wrote this letter, Sowle and the Stationers' Company owned the rights to this letter and could publish it as they pleased. Understanding the publisher of this letter and the contemporary British publication landscape provides greater insight into William Penn’s 1683 letter.

History of the Stationers' Company

The Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers—the complete name for the Stationers' Company—was one of the Livery Companies. The Livery Companies were a series of trade associations in the City of London that provided representation for certain industries, jobs, and/or trades. The Stationers' Company was originally founded in the 14th century; in 1403, the Mayor of London approved the assembly of a Guild of Stationers, whose members were booksellers, bookbinders, text writers, illuminators, and suppliers of parchment, pens, and paper. Thus, the Company at last offered membership to all trades involved in the printing industry. [4] This critical moment set the stage for how the Company tenuously monopolized the printing industry.

In 1476, when the invention of printing arrived in England, printers joined the Company. In 1557, the Company received a Royal Charter of incorporation, bestowing it with the power to restrict and control printing. [4] Outside competition could no longer exist.

Connection with William Penn's Letter

Because William Penn’s letter was written in 1683 and printed in London, the publisher logically would have been the Stationers' Company. This information was confirmed by curator John Pollack, who accessed further information on the letter and confirmed that, in fact, Andrew Sowle was a member of the Stationers’ Company.

Understanding the Stationers' Company is important for contextualizing the landscape of how William Penn’s 1683 letter was published. As a large monopoly, the Stationers' Company valued maximizing efficiency of materials and cost so that it could profit as much as possible. [4] The material of this letter—particularly the quality of paper and the folio gathering format—are evidence for how the Stationers' company efficiently mass-produced this letter and distributed it to members of the Free Society of Traders, whom William Penn intended to address. Additionally, because the members of the Free Society of Traders resided in either Dublin or London, [4] it was sensible for Penn to have his letter published by the Stationers' Company, whose offices were in close proximity to these two cities.

Material Analysis

Marginalia

This letter, given its old age, has been passed through the hands of many owners—with the first owners being the members of the Free Society of Traders, whom William Penn intended to directly address. In fact, a particular piece of marginalia written on the inside of the new binding describes an appraisal of the book’s value ($12,000) before the Kislak Center acquired it. This provides direct proof that the letter has been transferred at least once between the hands of one owner to another, since an appraisal is intended to value the sale of an item.

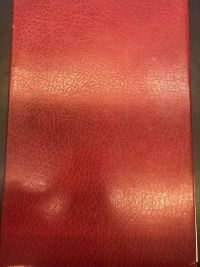

New Binding

In the field of bibliography, a significant worry for ephemerals that are handled by many people, including multiple owners, is accruing damage that can severely change the form of the piece. To counter this long-term deterioration, a new binding was incorporated around the letter, made out of a red leather-like material. The spine of the new binding read “Letter from William Penn. 1683,” which makes the work easily identifiable, despite the fact that the original papers are encased snugly and not directly visible. Although the spine appears quite new, it has some wear at the corners, illustrating the damage that could have been inflicted on the original papers but was counteracted by the binding. Clearly, this hardback, sturdy binding was designed to preserve the integrity of its valuable inner contents.

Paper

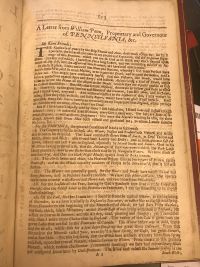

This letter is comprised of two distinct sets of paper: one set that constitutes the new binding, and another set that belongs to the original papers of the letter. The paper from the new binding appears to have slightly yellowed and darkened, indicating natural wear and aging. This paper also appears to have slight striations/chain lines in the vertical direction, which indicates that the paper is uniformly made and modern. This corroborates well with the fact that the new binding is much newer than the original papers. On the other hand, the original papers of William Penn’s letter are very stained and have lots of ink smears, perhaps from several users fingering through countless times, which would likely happen to a valuable letter over 300 years old. The ink bled through visibly between the recto and verso sides of the page, indicating that the paper is very thin—a common feature of paper in the 17th century. The original papers seem to consist of old rags and linens, based on the amorphous structure of the paper—another common feature of paper in the 17th century. All of these observations confirm that the original papers date back to 1683, and that the new binding was applied to the original papers centuries later.

Formatting

The formatting of the pages of this letter appears to be in folio, a common gathering type printed by the Stationers' Company. [4] The dimensions of each page in the original letter are 11.25 inches in height and 7 inches in width, which point to the pages being in folio. Folio was a convenient format because each sheet of paper would not have to be intricately printed with multiple pages that must be folded properly, like in quarto or octavo. Although folio does require more bulk paper, the fact that this letter is only several pages long makes this issue negligible. Rather than page numbers, the bottom of each page is marked with a signature mark. For example, the first page of content has the signature “A2.” Each side of each page can be described as either “recto” or “verso,” with the former describing the front side of the page on the right side of the book, and the latter describing the back side of the page on the left side of the book.

Long S's

A miscellaneous but critical element of the text is that long “S”’s are present. This element points to the writing and printing traditions in Britain at the time, which include this additional formality that is not present in modern English language printing. This small observation further confirms that this letter was written and printed in the 17th century.

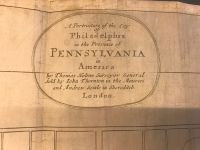

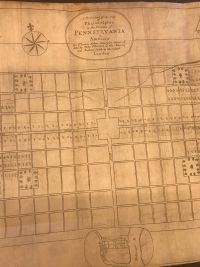

The Map of Philadelphia

At the end of William Penn’s 1683 letter, a large fold-out map of Philadelphia is included. The heading of the map indicates that Thomas Holme, the Surveyor General of the colony, [3] constructed the map and that Andrew Sowle, a member of the Stationers' Company, helped publish and print the map. Observing the detail of the map and the Stationers' Company’s contemporary methods for printing pictures, it was deduced that intaglio technology was utilized to print this map.

Intaglio technology involves carving a substrate—perhaps copper—with etchings that resemble the desired image. Ink is then submerged into these etchings, and the substrate is pressed firmly onto the page. This allows for a highly detailed, sharp-edged image to be produced on paper.

The map illustrates rectangular plots of land, even including trees and important numerical information. Prominent landmarks are also named, such as “Faire Mount” (modern-day Fairmount) and the “Scool Kill River” (modern-day Schuylkill River).

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Hull, William I. William Penn: A Topical Biography. Oxford University Press, 1937. https://heinonline-org.proxy.library.upenn.edu/HOL/Page?handle=hein.lbr%2Fwpentb0001&collection=lbr#.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 The Articles, Settlement, and Offices of the Free Society of Traders in Pennsilvania Agreed upon by Divers Merchants and Others for the Better Improvement and Government of Trade in That Province. University of Pennsylvania Libraries. London, 1682.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Wetherill, S. P. Philadelphia History. Hathi Trust Digital Library 2. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, PA: City History Society of Philadelphia, 1916. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=wu.89077214542&view=1up&seq=5&skin=2021.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Matthew, Adam. Literary Print Culture: The Stationers' Company Archive, 1554-2007. Adam Matthew Digital. Accessed April 5, 2022. https://www-literaryprintculture-amdigital-co-uk.proxy.library.upenn.edu/.