Curious Flap Anatomies - 19th Century Obstetrics

Overview

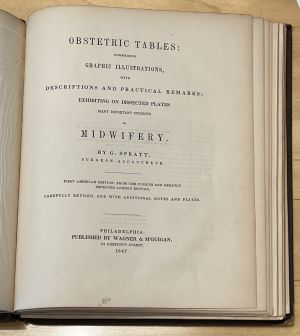

Obstetric Tables: comprising graphic illustrations, with descriptions and practical remarks; exhibiting on dissected plates many important subjects in midwifery by surgeon and accoucheur George Spratt is a medical text published in 1847.

This anatomical codex can currently be found in the University of Pennsylvania’s Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts. Through the use of detailed chromolithography book plates or flaps this book was crafted to help students of medicine and physicians visualize the stages of pregnancy and labor, techniques and/or equipment that could be used to help progress the birth, as well as easily access views that would usually only be possible via autopsy or surgery at the time such as the layers of tissue and the various fetal positions of the baby in the birth canal. This intricately created flap anatomy is accompanied by commentary and notes from both the author and doctor, George Spratt. This book can be accessed through the Penn Libraries.

Background

Historical Context

Codex Content

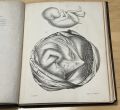

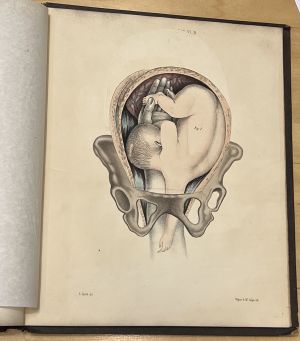

The depictions in this book can primarily be split into two categories: external and internal visualizations. Regarding internal depictions, Spratt’s codex offers a glimpse into in utero processes like the development of a fertilized egg into a fetus and how the size and shape varies at different points in time. This flap anatomy also provides virtual autopsy capabilities for its readers by showing the layers of tissues represented by each flap that need to be cut in order to perform a cesarean section for instance. Some drawings almost give an x-ray vision perspective since it shows the practioner’s hand reaching in to reposition a fetus or use forceps thereby allowing readers like medical students or physicians to imagine what they should feel for or where to expect their hand or tool placement to be during different approaches. This would be valuable information for physicians and students to have on hand whenever they need to refresh certain material quickly since performing an autopsy would likely be prohibitive and time consuming.

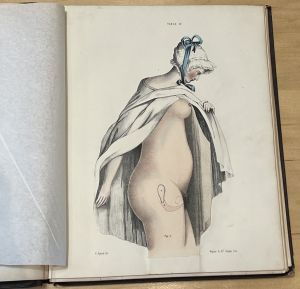

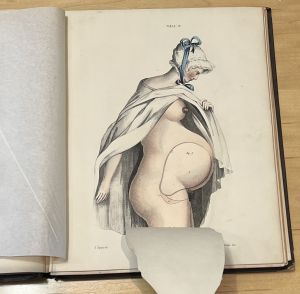

External depictions are more steeped in the historical context of the time. For example, the figure of the pregnant women in Victorian garb like a hat and a cape with makeup despite the purpose being to show the outward physical changes the body goes through during pregnancy. The flaps progressively show the stomach swell as the uterus expands and increased breast size as the pregnancy gets to later stages. This harkens back to the sexualization of female anatomy described above and how it made an appearance in Spratt’s works too.

Author of the Text

Lithography

Analysis of Materiality

Metadata

This codex was produced in 1847 and its author is George Spratt who was a surgeon and obstetrician. Wagner & M’Guigan were the publisher, copywriter, and lithographer for this codex and their shop was located at 116 Chestnut Street in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. This work on obstetrical science was the First American edition from the fourth London edition with additional notes and book plates. The preface below explains how this work had a great reputation in Europe and some copies were imported at a high cost, so there was demand to replicate it in America. Unfortunately, no lithographers wanted to take on this difficult feat due to the high cost and they worried it would turn out inferior to the original European version until Wagner & McGuigan’s lithography talent was discovered to be perfect for the job. Wagner & McGuigan successfully created this book at a lower cost and higher quality and were lauded for its accuracy and detailed depictions of procedures. In fact, the print shop received the highest award (a silver medal) for their lithography from the Franklin Institute from the State of Pennsylvania.

Physicality of the Book

Substrate

This anatomical codex looks to be made of wove paper as opposed to laid paper. The two can be distinguished because holding laid paper up to light will cause chain lines to become apparent while wove paper lacks this feature. The chain lines are produced when making laid paper which consists of catching rag-based pulp using a screen which has wires that create the characteristic lines. Wove paper pulp, often made of rags, lacks these lines and has a uniform surface due to the flat mesh paper-making molds used instead. Also, this type of paper was consistent with the time the codex was being produced. Unfortunately, the pastedown and primarily the first flyleaf at the beginning and end of the codex have extensive evidence of foxing which is an age-related process characterized by reddish brown spots as depicted below. The main causes are chemical contamination from ferric oxide used to coat paper or from the presence of fungi.

Binding

As for the binding, the book has original gilt cloth publisher’s binding which is brown with some cracking. Also, the title “SPRATTS Obstetric Tables 1847.” which is in gold lettering as well as the ornamental border design are indented impressions on the cover. Focusing on the cracked areas, the side covers seem to be made of compressed paper almost like cardboard and the lifting along the spine reveals the use of some printed waste binding. This was a common way to repurpose misprinted or surplus paper for reinforcement of the spine. For this codex, there appears to be two columns printed on the waste paper that was used to strengthen the spine and from what can be read it seems to be burial rules such as a cemetery code or guideline. This is likely evidence of some job printing materials being recycled and often these types of documents would solely be preserved in these forms and only uncovered in the event of damage because they were everyday papers not considered important enough to save for the future.

Format & Production

Regarding the bibliographical format of the atlas, each gathering appears to be comprised of an inconsistent number of pages. This might be due to the book plates which were glued in afterwards since they had to be made using lithography techniques separately while the rest which was text was produced by relief printing. In fact, the page pictured below specifies that the codex was stereotyped by E.B. Mears at 130 Race Street in Philadelphia. Stereotyping is the practice of making a solid plate of type metal cast from a mold taken of the surface of a form or page setup. This would be useful since this medical codex was going to be printed for many medical professionals and students in America and Europe for use as a textbook mostly and having these stereotypes would make production faster and more standardized since the type for each page would not have to be reset to print any additional copies ordered.

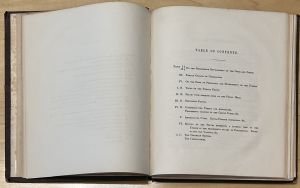

At the beginning of the book, there is a table of contents with the topics in numerical order. Then, the continuation of contents seems to have page number 2 at the bottom left of the page, but there is no other sign of pagination throughout the book. Nevertheless, the tables and figures are carefully labeled so the reader knows what book plate to reference when looking at the text descriptions and vice versa. The lack of numbered pages might make navigation a bit more difficult but the topics at least have corresponding table numbers which is a similar system. This book would mostly be used by doctors or medical students that may have needed to refresh or learn certain procedures or perspectives. Therefore, the lack of pagination would cause readers to go by titles that would start them at the beginning of each section which might improve their understanding of the material by maximizing their exposure to the detailed book plates and commentary. Without page numbers, readers are being forced to explore other parts of the codex in order to find their section of interest. In doing so, their attention will likely be piqued by some other book plate or description, encouraging them to read and view more of it.

There are no marginalia nor asemic marks in this book which further supports its use as a formal resource that was used as a reference especially since this a copy that belonged to the School of Medicine with no evidence of an earlier owner. Therefore, it was for shared use, so perhaps a physician’s personal copy might have had annotations or notes. On the same note, a book this pricey and artistic might have been gifted to a physician at the time and displayed rather than heavily used and annotated, so it would similarly be untouched like this copy.