Curious Flap Anatomies - 19th Century Obstetrics

Overview

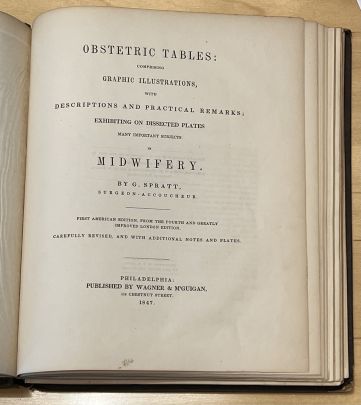

Obstetric Tables: comprising graphic illustrations, with descriptions and practical remarks; exhibiting on dissected plates many important subjects in midwifery by surgeon and accoucheur George Spratt is a medical text published in 1847.

This anatomical codex can currently be found in the University of Pennsylvania’s Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts. Through the use of detailed chromolithography book plates or flaps this book was crafted to help students of medicine and physicians visualize the stages of pregnancy and labor, observe techniques and/or equipment that could be used to help the birthing process, as well as have access to views that would usually only be possible via autopsy or surgery like seeing the layers of tissue and the various positions of a fetus in the birth canal. This intricately created flap anatomy edition is accompanied by commentary and notes from both the author and doctor, George Spratt. This book can be accessed through the Penn Libraries.

-

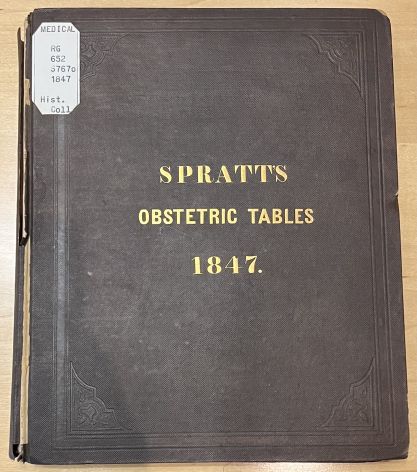

Spratt's Obstetric Tables - Cover

-

Spratt's Obstetric Tables - Title Page

Background

Historical Context

The 19th century is known as the “golden age” of flap books or virtual autopsies which combined refined printing elements and anatomical parts to bring a glimpse of complex human anatomy to medical students, doctors, graphic artists, and a curious general audience alike. [1] The precursor to this is considered to be volvelles from the late Middle Ages which are rotating disks made from sheets of paper that were used for astronomical texts while flaps were almost exclusively used in anatomical works.[1] One of the first flap books is Carlino’s Paper Bodies from the 1530s which he called “fugitive sheets.”[1] In fact, it is believed by many scholars that these sheets were created for barbers and surgeons to place on their walls like informational broadsides.[2] These flap anatomies were created during a time when dissection was not common nor legal in many places, so they provided much needed information about human anatomy that was necessary to teach physicians and midwives just to name a few. [2]

The technology of early flap anatomies is not well known, but for books in the hand press period with less intricate parts printers would send binders detailed instructions on how to assemble the pieces.[1] However, fugitive sheets required more collaboration due to their intricacy while the machine printing press allowed for more accurate, efficient techniques. Later, developments in the production of printed images allowed anatomists like Edward Tuson, George Spratt, and others to readily provide traditional animated flap anatomies in the 1800s to practitioners who increasingly valued the educational potential of these illustrations.[1] In particular, the popularity and vital role of lithography techniques is expanded upon in later sections. One way these were assembled is like Spratt’s Obstetric’s tables which layered paper flaps each with different illustrations representing a different stage of the process and the image below shows how the flaps make the bookplate pages thicker. To accommodate the extra paper a portion of the bottom sheet is removed to make room for the flaps so they would sit flush on the surface of the paper.[1]

Furthermore, the latter half of the 19th century experienced a health movement that spurred the public to advocate for sex education which led to the publication of detailed anatomical books that explained bodily processes.[1] Due to this, some graphic flap books had lock-and-key devices for a variety of reasons spanning from conservative views, to publishers trying to avoid obscenity charges, and protecting young boys and women from this kind of exposure.[1] At the time, anatomical texts referencing women primarily focused on their sexual parts and that stirred up the public over how appropriate that was to depict. Along these lines, Spratt’s tables reflected the cultural and social implications and turmoil of its time because it engaged with social norms and anxieties over nudity and sexuality while interacting with medical literature and popular print. At the time, wider print culture was growing in popularity and diversity of subject matter to the point that obscene content was becoming cheaper and more commonplace.[3] That led to moral panic surrounding the corruption and sexualization of women and children who might encounter such material.[3] To some extent, it may be said that certain images in Spratt’s books play to the obscene tropes of the time and were not purely for science like those present in other works. For example, there is a particular book plate of Spratt's that only shows a lower torso with female genitalia and has flaps but does not reveal an embryo or show a cross-section into the body like the rest of the codex does, but rather makes a part of the body manipulable. Thus, Spratt’s works seem to walk the line between medical and obscene, especially at a time when the public was morally trying to fight such print materials and the presence of male physicians in the birthing process was not widely accepted by society. However, Spratt's tables were not so outrightly sexual that they were banned, but discussions surrounding what kinds of materials should be printed and circulated versus what was deemed medical were happening at the time.

-

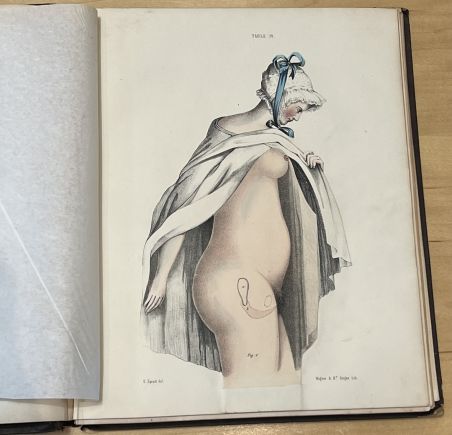

Victorian woman in Early Stage Pregnancy

-

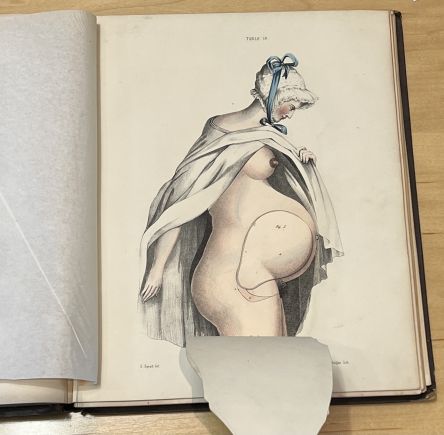

Victorian woman in Late Stage Pregnancy

Codex Content

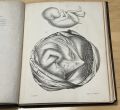

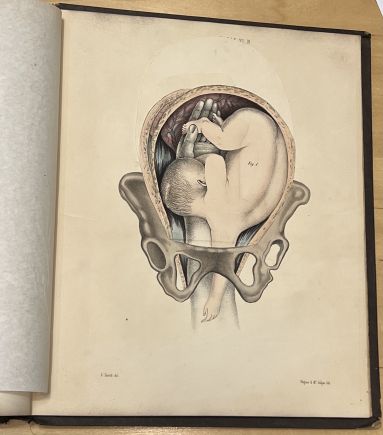

The depictions in this book can primarily be split into two categories: external and internal visualizations. Regarding internal depictions, Spratt’s codex offers a glimpse into in utero processes like the development of a fertilized egg into a fetus and how the size and shape varies at different points in time. This flap anatomy also provides virtual autopsy capabilities for its readers by showing the layers of tissues represented by each flap that need to be cut in order to perform a cesarean section for instance. Some drawings almost give an x-ray vision perspective since it shows the practioner’s hand reaching in to reposition a fetus or using forceps thereby allowing readers like medical students or physicians to imagine what they should feel for or where to expect their hand or tool placement to be during different procedures. This would be valuable information for physicians and students to have on hand whenever they need to refresh certain material quickly since performing an autopsy would likely be prohibitive and time consuming.

-

Lithograph depicting delivery technique

-

Lithograph depicting forcep technique

External depictions are more steeped in the historical context of the time. For example, the figure of the pregnant woman in Victorian garb like a hat and a cape with makeup despite the purpose being to show the outward physical changes the body goes through during pregnancy. The flaps progressively show the stomach swell as the uterus expands and increased breast size as the pregnancy gets to later stages. The contrast of the traditional, conservative fashion of the time with the nude woman is contradictory and salacious. This harkens back to the sexualization of female anatomy described in previous sections and how it made an appearance in Spratt’s works too.

Author of the Text & Paratexts

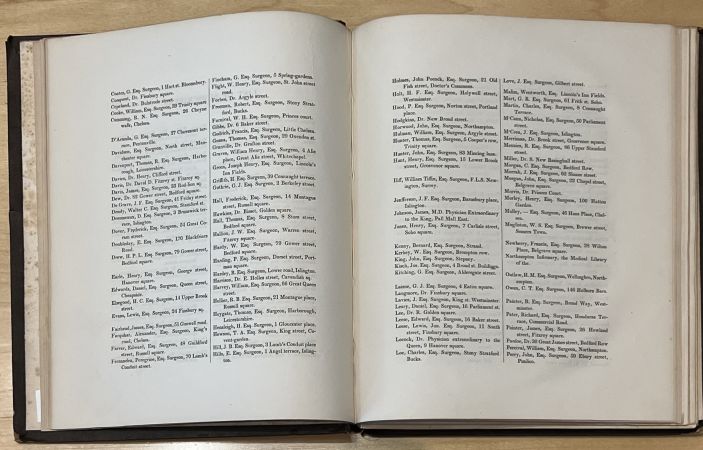

George Spratt was both the author and artist of the Obstetric Tables and his status as a medical practitioner as well likely made his works more accurate than those usually made by artists, but directed by medical authors. [3] Even though Spratt claimed to be a “surgeon-accoucheur” on the title page of the codex, evidence points to him being an unsuccessful medical practitioner such as his two bankruptcies in England and the fact that neither the Royal College of Surgeons nor the Linnaean Society had a record of him despite some biographies suggesting he was associated.[3] Therefore, he seems to have been part of the growing class of physicians who struggled to make a living so they took on other work. At the time, drawing was a skill many would learn in school, but it was interesting that Spratt did not completely abandon medicine and instead merged science and art to make his living and the frontispiece in the codex mentions his combination of skills. Originally, his book was meant to be for more casual readers, but it ended up enticing professionals as well because it helped male physicians become acquainted with the female-led practice of midwifery which they were beginning to expand into. [3] Thus, the tables were characterized as a useful revision guide that was largely purchased by established surgeons and practitioners due to its moderate to high price tag.[3] This explains the extensive list of medical professionals the American edition had as subscribers because not only was it intricate, costly work to assemble these detailed codices, but there was high demand from all over.

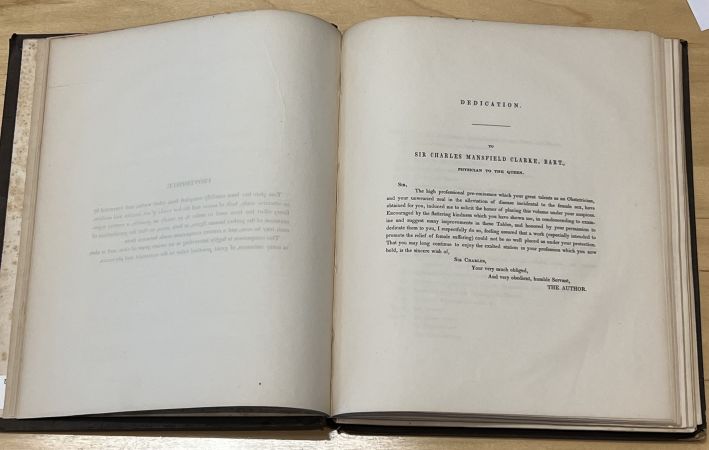

Additionally, Spratt's has a dedication to the Queen's physician which is signed off as "your very much obliged, very obedient servant" and there may be various reasons for this. It may be related to the fact that Spratt wanted to be in his good graces because this was the first American Edition of the tables, possibly because he is English, or since Europe was deemed at the height of medical knowledge. However, it may have to do with the fact that Spratt was an unsuccessful physician who claimed to be part of medical societies he was not a part of and he may have figured approval from the royal physician on his work might legitimize his position and knowledge.

-

Spratt's Merging of Art & Science

-

One of Many Pages of Subscribers

-

Spratt's Dedication to the Queen's Physician

Lithography

Lithography was invented in Germany in 1798 by Alois Senefelder and it is a planographic printing process that is based on the immiscibility of oil and water. [4] The process begins when a design is drawn onto a stone slab using a waxy crayon, the stone is moistened, then oil-based ink is rolled over the stone adhering only to the wax drawing while being repelled by the wet stone, and then sent through a printing press. [4]

The birth of American lithography began with the production of the country’s first lithograph by Bass Otis in 1819. [4] Commerically, lithographic production began in Philadelphia in 1828 and in 50 years the industry grew to include over 500 skilled workers. [4] The most influential figure in lithography was Peter Duval who arrived in Philadelphia in 1831 and was the only professionally trained lithographer. [4] His firm became a training ground for printmakers and due to his dedication to technological improvement, Philadelphia became one of the first cities in the US to use steam power for lithographic printing, and by the 1860s he figured out how to automate the rest of the process. [4] Duval then experimented with color printing and his artists so skillfully reproduced oil paintings that a new industry focused on chromolithography emerged in Philadelphia. [4] Some of his chromolithography competitors were Wagner and McGuigan which printed George Spratt’s Obstetric Tables. Similarly, Wagner and McGuigan were skilled lithographers who elevated the trade from practical printing to a fine art form that made detailed works accessible to a greater audience. Firms like these made Philadelphia a hub for printing innovation and they continued to make their art available to the public well into the 1900s.[4]

Analysis of Materiality

Metadata

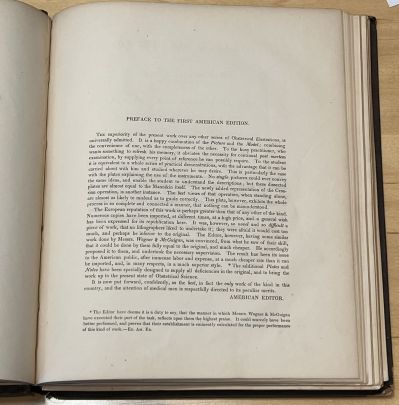

This codex was produced in 1847 and its author is George Spratt who was a surgeon and obstetrician. Wagner & M’Guigan were the publishers, copywriters, and lithographers for this codex and their shop was located at 116 Chestnut Street in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. This work on obstetrical science was the First American edition from the fourth London edition with additional notes and book plates. The preface below explains how this work had a great reputation in Europe and some copies were imported at a high cost, so there was demand to replicate it in America. Unfortunately, no lithographers wanted to take on this difficult feat due to the high cost and they worried it would turn out inferior to the original European version until Wagner & McGuigan’s lithography talent was discovered to be perfect for the job. Wagner & McGuigan successfully created this book at a lower cost and higher quality and were lauded for its accuracy and detailed depictions of procedures. In fact, the print shop received the highest award for quality, a silver medal, for their lithography from the Franklin Institute from the State of Pennsylvania.

-

Title Page

-

Preface

-

Page dedicated to Wagner & M'Guigan's lithography shop

Physicality of the Book

Substrate

This anatomical codex looks to be made of wove paper as opposed to laid paper. The two can be distinguished because holding laid paper up to light will cause chain lines to become apparent while wove paper lacks this feature. The chain lines are produced when making laid paper which consists of catching rag-based pulp using a wire screen that ends up creating the characteristic lines. Wove paper pulp, often made of rags, lacks these lines and has a uniform surface due to the flat mesh paper-making molds used instead. Also, this type of paper is consistent with the time this codex was being produced. Unfortunately, the pastedown and primarily the first flyleaf at the beginning and last flyleaf at the end of the codex have extensive evidence of foxing which is an age-related process characterized by reddish brown spots as depicted below. The main causes are chemical contamination from ferric oxide used to coat paper or from the presence of fungi that might grow in humid conditions.

-

Pastedown with Foxing

-

Flyleaf with Foxing

Binding

As for the binding, the book has original gilt cloth publisher’s binding which is brown with some cracking. Also, the title SPRATTS Obstetric Tables 1847. which is in gold lettering as well as the ornamental border design are indented impressions on the cover. Focusing on the cracked areas, the side covers seem to be made of compressed paper almost like cardboard and lifting along the spine reveals the use of some printed waste binding. This was a common way to repurpose misprinted or surplus paper for reinforcement of the spine. For this codex, there appears to be two columns printed on the waste paper that was used to strengthen the spine and from what can be read it seems to be burial rules such as a cemetery code or guideline. This is likely evidence of some job printing materials being recycled and often these types of documents would solely be preserved in these forms and only uncovered in the event of damage because they were everyday papers not considered important enough to save for the future.

Format & Production

Regarding the bibliographical format of the atlas, each gathering appears to be comprised of an inconsistent number of pages. This might be due to the book plates which were glued in afterwards since they had to be made using lithography techniques separately while the rest which was text was produced by relief printing. In fact, the page pictured below specifies that the codex was stereotyped by E.B. Mears at 130 Race Street in Philadelphia. Stereotyping is the practice of making a solid plate of type metal cast from a mold taken of the surface of a form or page setup. This would be useful since this medical codex was going to be printed for many medical professionals and students in America and Europe as an academic resource and having these stereotypes would make production faster and more standardized since the type for each page would not have to be reset to print any additional copies ordered.

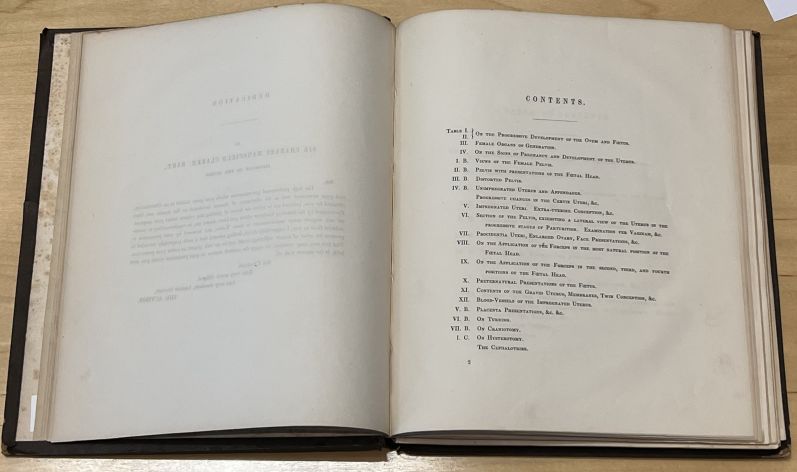

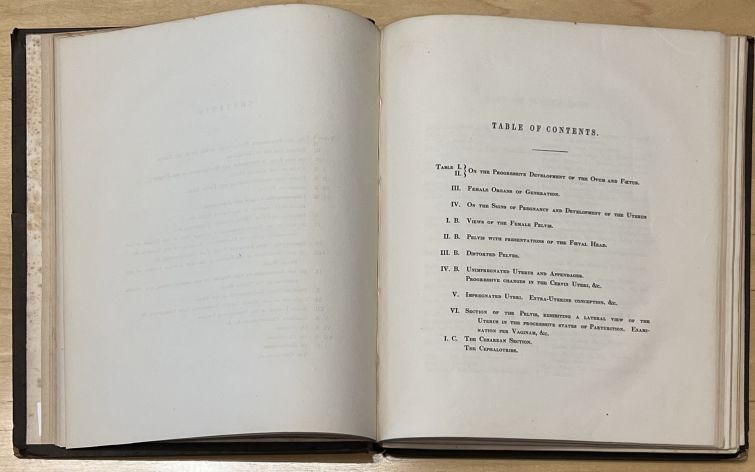

At the beginning of the book, there is a table of contents with the topics in numerical order. Then, the continuation of contents seems to have page number 2 at the bottom left of the page, but there is no other sign of pagination throughout the book. Nevertheless, the tables and figures are carefully labeled so the reader knows what book plate to reference when looking at the text descriptions and vice versa. The lack of numbered pages might make navigation a bit more difficult but the topics at least have corresponding table numbers which is a similar system. This book would mostly be used by doctors or medical students that may have needed to refresh or learn certain procedures or perspectives. Therefore, the lack of pagination would cause readers to search by title of section which leads them to the beginning of each section. This might improve their understanding of the material by maximizing their exposure to the detailed book plates and commentary since they are almost encouraged to read the whole section. Also, without page numbers, readers are being forced to explore other parts of the codex in order to find their section of interest. In doing so, their attention will likely be piqued by some other drawing or description, encouraging them to read more of it.

-

Table of Contents

-

Continuation of Contents

There are no marginalia nor asemic marks in this book which further supports its use as a formal resource that was used as a reference especially since this a copy that belonged to the School of Medicine's library with no evidence of an earlier owner. Therefore, it was for shared use, so perhaps a physician’s personal copy might have had annotations or notes. On the same note, a book this pricey and artistic might have been gifted to a physician at the time and displayed rather than heavily used and annotated, so it would similarly be untouched like this copy. The only writings in the codex are in pencil on the School of Medicine's ownership label and the first flyleaf and they appear to be a call number from when it was a part of the medical library since it matches the information on the sticker on the front cover.

-

Obstetric Tables Front Cover

-

Medical Library Ownership Label of this Copy

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Perkins Gallery. "Animated Anatomies: The Human Body in Anatomical Texts from the 16th to 21st Centuries. Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, April 6 - July 17, 2011."

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Brown, Meg. Flip, Flap, and Crack: The Conservation and Exhibition of 400+ Years of Flap Anatomies (2013): 6.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Whiteley, Rebecca. "Spratt’s Flaps: Midwifery, Creativity, and Sexuality in Early Nineteenth-Century Visual Culture", British Art Studies, Issue 19

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Donnelly, Michelle. Printmaking. The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. Rutgers University. (2015): 6.