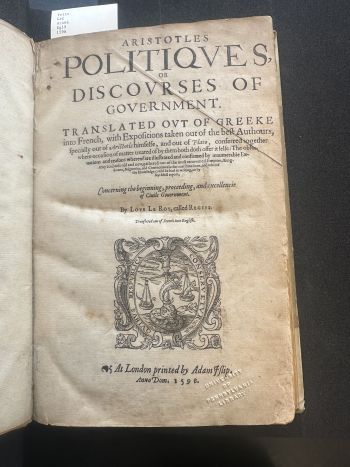

Aristotle's Politiques (London 1598)

Aristotle's Politiques is a collection of past works from both Aristotle and Plato that was published in 1598 in London by Adam Islip. The text was translated multiple times from Greek to French and finally English for this publication. The French translation was previously written by Loys le Roy also known as Regius and the English translation was completed by John Dee. The compilation of these texts were gathered across “The most renowned empires, kingdoms, seignories and commonwealths whereof the knowledge could be had in writing, or by faithfull report…” highlighting the diverse nature and rediscovery of these ancient ideas. These ideas themselves revolve around Aristotle’s ideas of government and examinations of Greek city-states representing both philosophical and empirical observations of society. The book compiles a broad ranging and comprehensive commentary and analysis with topics ranging from human nature, the role of households, constitutions, and governments to justice, individuals, and other philosophical foundations.

Publisher Context

Adam Islip was a London publisher during the late 16th and early 17th centuries. His printer device can be found on the title page of this book and he was an Apprentice and member of Stationers’ Co which still exists today. Islip appears to have published many books during this time period in addition to artwork and prints. These woodcuts were often made of previous original engravings. He’s published works from a broad range of content including poems from Geoffrey Chaucer and portraits of kings.

Translator Context

French Translation

The French Translator Loys Le Roy, also known as Regius was a translator and classicist at the College Royal. He first published and translated to French a commented version of Aristotle’s politiques as a member of Michel de Vascosan’s workshop in Paris 1568. This publication was significant as it served as the reference text for many of Aristotle’s ideas until the end of the eighteenth century. Le Roy was an active member of the renaissance humanist movement and its subsequent community studying both Latin and Greek classics and sharing his latinist knowledge with the Parisian intellectual scene. He continued to translate important Greek authors like Xenophon, Isocrates and more.

English Translation

The English Translator John Dee was a mathematician, astronomer and most notably advisor to Queen Elizabeth I. He was highly respected in mathematics and ended up turning down professor positions at both the university of Paris and Oxford in hopes of seeking an official position with the English crown. He eventually succeeded offering his services as a scientific and medical advisor to the queen where he quickly established himself as an influential figure in English politics. He was commissioned by the Queen to produce a report on the state of the nation’s political, economic and social affairs known as the Summary of the Commonwealth of Britain in which he identified the nation's problems and used to lobby Queen Elizabeth for more expansionist policies. Dee was an avid supporter of English colonialism and was heavily involved in preparing their ships for exploration voyages. He was credited with being one of the main architects of England’s imperial vision being the first to use the term “British Empire”. Dee was also heavily tied to the intellectual community of England. He personally owned one of the largest private libraries in England at the time that contained more than 4,000 books and manuscripts. Moreover, he made this library accessible to scholars and assisted numerous researchers seeking materials. He was fascinated by all things knowledge related including translating. He notably edited the first English translation of Euclid’s Elements (1570) and also translated Aristotle’s Politiques. Dee was also heavily involved in Alchemy, magic, and astrology which eventually led to his downfall as James I was not interested and refused to believe in his magic powers.

Book as a Physical Object

Substrate/Format

The book is made and printed from paper, specifically linen rags. The texture is worn and old as to be expected due to the age of the text and feels similar to a bill or note. The book is compact in size and looks to be an edition printed to be read and studied out of. The book is similar to a modern book in its composition and the binding is intact. There is not anything particularly distinct other than the fact that the corners of the front and back are slightly discolored. This leads me to believe that perhaps the book had some sort of strap or was stored in a particular manner. The book is a Folio, it is rectangular and looks like a modern book in terms of shape and size. There are multiple books that are collected within this text including works from Aristotle and Plato and within these books there are chapters. There is a table of contents at the end. The book is very well bound.

The book contains a table of contents at the back that is very comprehensive with full page numbers books, chapters and specific topics. This tells us that this book was likely read by academics as it refers to subject areas that are discussed almost akin to a textbook. It tells us that it was likely consumed by highly skilled and educated readers during this time period.

Evidence of Readership and Circulation

This specific copy was given to the University of Pennsylvania by Dr. C.W. Burr. It was acquired on July 7, 1933 as a gift to the Kislak Library. The book itself has been written in with what appears to be pencil markings with some highlighter stains indicating that the physical interpretations noted on the book were likely made long after it was originally printed. The annotations aren’t very detailed, usually highlighting only a couple of words or some numbers indicating a location or city. We know that the book was widely read by scholars and prominent in the academic community around the time of its printing. However, clearly they weren’t making notes and annotations at the time. This English translation was read by notable English intellectuals and other respective versions followed similar trends in their nations.

book [1]