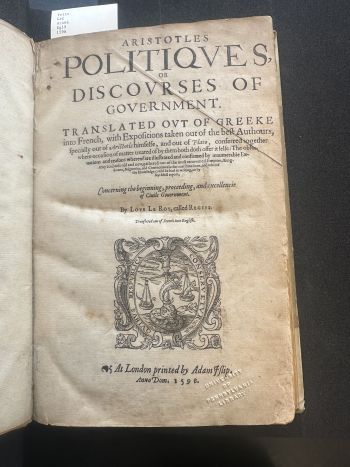

Aristotle's Politiques (London 1598)

Aristotle's Politiques is a collection of past works from both Aristotle and Plato that was published in 1598 in London by Adam Islip. The text was translated multiple times from Greek to French and finally English for this publication. The French translation was previously written by Loys le Roy also known as Regius and the English translation was completed by John Dee. The compilation of these texts were gathered across “The most renowned empires, kingdoms, seignories and commonwealths whereof the knowledge could be had in writing, or by faithfull report…” highlighting the diverse nature and rediscovery of these ancient ideas. These ideas themselves revolve around Aristotle’s ideas of government and examinations of Greek city-states representing both philosophical and empirical observations of society. The book compiles a broad ranging and comprehensive commentary and analysis with topics ranging from human nature, the role of households, constitutions, and governments to justice, individuals, and other philosophical foundations.

Publisher Context

Adam Islip was a London publisher during the late 16th and early 17th centuries.[1] His printer device can be found on the title page of this book and he was an Apprentice and member of Stationers’ Co which still exists today.[2] Islip appears to have published many books during this time period in addition to artwork and prints. These woodcuts were often made of previous original engravings. He’s published works from a broad range of content including poems from Geoffrey Chaucer and portraits of kings.[3]

Translator Context

French Translation

The French Translator Loys Le Roy, also known as Regius was a translator and classicist at the College Royal. He first published and translated to French a commented version of Aristotle’s politiques as a member of Michel de Vascosan’s workshop in Paris 1568. This publication was significant as it served as the reference text for many of Aristotle’s ideas until the end of the eighteenth century.[4] Le Roy was an active member of the renaissance humanist movement and its subsequent community studying both Latin and Greek classics and sharing his latinist knowledge with the Parisian intellectual scene. He continued to translate important Greek authors like Xenophon, Isocrates and more.[4]

English Translation

The English Translator John Dee was a mathematician, astronomer and most notably advisor to Queen Elizabeth I. [5] He was highly respected in mathematics and ended up turning down professor positions at both the university of Paris and Oxford in hopes of seeking an official position with the English crown. He eventually succeeded offering his services as a scientific and medical advisor to the queen where he quickly established himself as an influential figure in English politics. He was commissioned by the Queen to produce a report on the state of the nation’s political, economic and social affairs known as the Summary of the Commonwealth of Britain in which he identified the nation's problems and used to lobby Queen Elizabeth for more expansionist policies. [6] Dee was an avid supporter of English colonialism and was heavily involved in preparing their ships for exploration voyages. He was credited with being one of the main architects of England’s imperial vision being the first to use the term “British Empire”. Dee was also heavily tied to the intellectual community of England. He personally owned one of the largest private libraries in England at the time that contained more than 4,000 books and manuscripts. [7] Moreover, he made this library accessible to scholars and assisted numerous researchers seeking materials. He was fascinated by all things knowledge related including translating. He notably edited the first English translation of Euclid's Elements (1570) and also translated Aristotle’s Politiques.[7] Dee was also heavily involved in Alchemy, magic, and astrology which eventually led to his downfall as James I was not interested and refused to believe in his magic powers.

Book as a Physical Object

Substrate/Format

The book is made and printed from paper, specifically linen rags. The texture is worn and old as to be expected due to the age of the text and feels similar to a bill or note. The book is compact in size and looks to be an edition printed to be read and studied out of. The book is similar to a modern book in its composition and the binding is intact. There is not anything particularly distinct other than the fact that the corners of the front and back are slightly discolored. This leads me to believe that perhaps the book had some sort of strap or was stored in a particular manner. The book is a Folio, it is rectangular and looks like a modern book in terms of shape and size. There are multiple books that are collected within this text including works from Aristotle and Plato and within these books there are chapters.

The book contains a table of contents at the back that is very comprehensive with full page numbers books, chapters and specific topics. This tells us that this book was likely read by academics as it refers to subject areas that are discussed almost akin to a textbook. It tells us that it was likely consumed by highly skilled and educated readers during this time period.

Evidence of Readership and Circulation

This specific copy was given to the University of Pennsylvania by Dr. C.W. Burr. It was acquired on July 7, 1933 as a gift to the Kislak Library. The book itself has been written in with what appears to be pencil markings with some highlighter stains indicating that the physical interpretations noted on the book were likely made long after it was originally printed. The annotations aren’t very detailed, usually highlighting only a couple of words or some numbers indicating a location or city. We know that the book was widely read by scholars and prominent in the academic community around the time of its printing. However, clearly they weren’t making notes and annotations at the time. This English translation was read by notable English intellectuals and other respective versions followed similar trends in their nations.

Historical Context

Origin of Aristotle’s Politics

Aristotle was an ancient Greek philosopher and scientist and is often credited with building the foundations of many concepts of Western thinking from logic to society. Aristotle’s “Politics” was originally written around 350 B.C. a time period in which philosophy was generally orally instructed. Aristotle himself primarily taught in the Lyceum, a temple best known for the peripatetic school of philosophy that he founded. [8] Due to a lack of printing technology, as well as an emphasis on live interactive discussion, the few handwritten manuscripts that existed were highly limited and primarily circulated amongst the academic community. However, his lectures and notes were popular and circulated between students, later being compiled by followers. Given this fact combined with the difficulty of manually copying notes by hand there exists concerns regarding the potential divergences and alterations from his original lectures.[9] Nevertheless, many of his ideas were re-examined during the Renaissance following the invention of the printing press and its ensuing transformation of knowledge access.

The Renaissance and Humanism

Renaissance, directly translated as “Rebirth” in French was a period in European history that saw a rediscovery of classical influences in both art and eventually, sparked by humanist scholars, an enlightenment period that repurposed ideas regarding society and governments.[10] Classical philosophers like Aristotle and Plato had their works integrated into the modern political discussion and studied by scholars inspiring a new wave of western thinkers and consequently revolutions. Aristotle’s “politiques” in particular was significant in its analysis of ancient Greek city-states that resembled the political organization of a disjoint Italy and many other equally conflicted Western European nations. Politiques sparked debate amongst scholars and aristocrats, the predominant leaders of the Renaissance, regarding the nature of leadership and ideal forms of government. His categorization of governments into types: monarchies, aristocracies, democracies in addition to their corrupt contrasts: tyranny, oligarchy, and ochlocracy served as almost an encyclopedia for analyzing European governments for centuries.

English Political History

By the late 16th and early 17th century in England the Renaissance was already well established. Following the Elizabethan period that birthed Shakespeare there was also an artistic revolution declared the Jacobean era in which England developed its own unique style of renaissance art that featured more baroque influences.[11] Politically however, England, despite having a monarchy, was in many ways developmentally ahead of its time in terms of democratic ideals and the moral purpose of government. Indeed, it was the only Western European country that had a historically preserved legal government establishing the limited power of a monarch. The Magna Carta signed 1215 nearly 400 years prior to the publication of in English of Aristotle’s Politiques established an agreement between King John and the Barons of England that declared certain rights and to some extent separation of government and checks on the kings tyrannical power. [12] Although the Magna Carta was groundbreaking by mere existence in writing it had a few differences with how Aristotle’s ideas later influenced the country. The Magna Carta wasn’t signed for the people, or by some declaration for equality in representation, rather the tension between rebel nobles and the crown had escalated to a point in which war was inevitable.[13] Thus, this was more of a peace treaty than a thought out politically charged revolution.

Influence on Hobbes and Locke

Aristotle’s “Politiques” however would change this as his rediscovered ideas influenced some of the most critical enlightenment thinkers across Europe as they read his Politiques. In England specifically both Thomas Hobbes and John Locke echoed Aristotelian rhetoric throughout their works. Aristotle was the classic source for one of Locke’s most famous papers, his second Treatise on government. Aristotle was the inspiration for both the theoretical argument and method to pursue it. Specifically, Locke was interested in his methodical analysis of power.[14] In fact Locke was known to be pursuing a variation on book 1 of Aristotle’s Politiques and he wasn’t the only one to do so.[14]

Thomas Hobbes, author of the Leviathan, an influential political document that describes the nature of human society and how government remedies its issues, was also well-read in classical literature and intensely familiar with Aristotle’s work. In fact, in the Leviathan chapter XXI Hobbes writes “In these western parts of the world we are made to receive our opinions concerning the institution and rights of commonwealths from Aristotle, Cicero and other men, Greeks and Romans…”. Although the context of his referencing is critical of some classical thoughts his mere reference and study of them reflects the influence its had on his own politics and subsequently future politics. In fact, Hobbes adopted this view and his infamous pessimistic lens of human nature during the English Civil War. [15] By his own account in his Vita, Hobbes at Oxford was fascinated by classical and humanist texts between 1608 when he left Oxford and 1628 where he published his own translation of Thucydides. Hobbes describes himself that it was the Civil Wars that “Ripened and Plucked” the third part of his philosophy from him before its natural predecessors were ready and all the knowledge of man needed for political theory he had already obtained.[15] The ideas of Hobbes and Locke, both drawing influence from Aristotle’s Politiques would go on to influence the American revolution and many of its ideas.

References

- ↑ “Collections Online: British Museum.” Collections Online | British Museum, www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG211499.

- ↑ British Book Trade Index, bbti.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/details/?traderid=100127.

- ↑ “Antiques Roadshow: Appraisal: 1602 Adam Islip-Published Chaucer Works: Season 22: Episode 7: Arkansas PBS.” Arkansas PBS Video, watch.myarkansaspbs.org/video/appraisal-1602-adam-islip-published-chaucer-works-1rqllr/.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Severini, Maria Elena. “Le Roy, Loys.” Encyclopedia of Renaissance Philosophy, 2017, pp. 1–9, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-02848-4_203-1.

- ↑ Murdin, Paul. “Dee, john.” The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers, 2007, pp. 285–286, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-30400-7_345.

- ↑ “John Dee.” Royal Museums Greenwich, www.rmg.co.uk/stories/topics/john-dee.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 “John Dee.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., 5 Apr. 2024, www.britannica.com/biography/John-Dee.

- ↑ “Aristotle.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., 23 Apr. 2024, www.britannica.com/biography/Aristotle.

- ↑ Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, iep.utm.edu/aristotle-politics/.

- ↑ “Renaissance Period: Timeline, Art & Facts.” History.Com, A&E Television Networks, www.history.com/topics/renaissance/renaissance.

- ↑ “The Renaissance Period: 1550–1660.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., www.britannica.com/art/English-literature/The-Renaissance-period-1550-1660.

- ↑ “Magna Carta.” National Archives and Records Administration, National Archives and Records Administration, www.archives.gov/exhibits/featured-documents/magna-carta.

- ↑ Worcester K. The Meaning and Legacy of the Magna Carta: Editor’s Introduction. PS: Political Science & Politics. 2010;43(3):451-456. doi:10.1017/S1049096510000569

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Maloy, J. S. “The Aristotelianism of Locke’s Politics.” Journal of the History of Ideas, vol. 70, no. 2, 2009, pp. 235–57. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40208102.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Laird, J. “Hobbes on Aristotle’s ‘Politics.’” Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, vol. 43, 1942, pp. 1–20. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4544372.