William Pybus Book of Recipes, Remedies, and Experiments

Overview

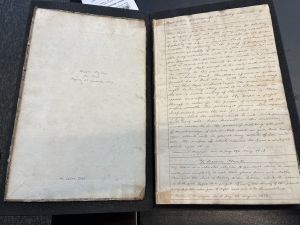

Written and compiled in England between 1815 and 1816, the William Pybus book of recipes, remedies, and experiments includes 382 entries highlighting remedies, experiments, and inventions of the day. Covering a large range of topics, the book contains entries that discuss how to handle flesh wounds, new measuring tool technologies, and methods of churning butter, among many others. With a binding made of half-leather covering paper boards, the book has no evidence of ever being published and looks to have been created for personal reference and use. Hand-drawn illustrations span the book's pages, mostly depicting the dimensions of new inventions or showcasing how they operate. The book now resides in the Kislak Center for Special Collections at the University of Pennsylvania, obtained by the University of Pennsylvania via the Edgar Fahs Smith Memorial Collection. Pybus’s book provides valuable insight into technologies of the early 19th century, and the progress being made during the height of the industrial revolution.

Background

Genre and Historical Context

Recipe and Remedy Books

Recipe books are more than a collection of culinary instructions – they also serve as an archeological tool documenting a snapshot of domestic life, medicine, and cultural practices.[1] During the early modern period in England between 1575 and 1650, recipe books were at the height of their publication, notably being one of the few written forms which women would engage in for social networking and collaborative experimenting. These books would discuss food preparation but also included medicinal remedies. As such, recipe books provided English women with a platform for self-definition and an opportunity to contribute to the family's and community's well-being, while also participating in broader discussions about gender and societal roles.[2]

The concept of merging culinary guidance with medicinal remedies was not just limited to England alone but was seen in countries all over the world during the early modern period. In Ireland, manuscripts of recipe books served as educational tools for affluent households, blending cooking techniques with therapeutic remedies.[3] Similarly, in Korea, the exploration of cookbooks spanning from the 1800s to the 1990s reveals a diverse array of pheasant recipes categorized by cooking methods, alongside the incorporation of ingredients essential to traditional healing practices.[4] These examples from across cultures highlight how recipe books have historically functioned as important repositories for culinary and medicinal wisdom, highlighting how food became a cornerstone of health and cultural identity.

Recipe books are now considered historical literature, reflecting more than just culinary instructions. Moving forward in time to examine 19th-century cookbooks, they served as guides for managing large households, providing extensive culinary advice, household management tips, moral education, and medical remedies.[5] The legacy of recipe books continues even today, evolving with new technologies and changing dietary trends, yet remaining as fundamental resources in kitchens worldwide.

The Industrial Revolution

The writing of Pybus’s book came amidst Britain’s Industrial Revolution, which lasted from 1760 to 1840. The revolution created an economic landscape noted for its unique wage and price structures. These economic conditions incentivized the development of labor-saving technologies that replaced manual labor with time-saving technologies. High relative wages increased the affordability of education, fostering a skilled workforce that further spurred innovation.[6]

Additionally, the abundance and low cost of coal in Britain played a crucial role in supporting the feasibility and adoption of new technologies that are featured in Pybus’s volume. This cheap, accessible energy source enabled the economical use of new mechanical inventions that would have been too costly elsewhere, due to higher energy prices and lower wages. This era of prosperity was deeply interwoven with the content of Pybus’s book, which included detailed illustrations and descriptions of contemporary inventions and scientific achievements.

Content

Pybus’s book of recipes, remedies, and experiments was written in a oversized, faded brown bound notebook. The binding of the cover has since worn down, and the cover has split from the rest of the book. Pybus, the author of this manuscript, filled all 188 pages over the span of a single year, starting on November 2nd, 1815 and finishing it in 1816. The writing is a thin cursive scrawl in black ink, and the entire page is always used, other than a thin empty margin on the left side of every page.

There are a variety of food recipes (including lemon vinegar, potatoes, and turnip bread), household chore instructions (such as preparing soap from fish), medicinal techniques (like a treatment to scarlet fever), inventions (such as a boiler for the use of tallow candle production, and a plinth to hold a door up so it doesn’t drag on carpet), and miscellaneous topics of Pybus’s choosing (including a method of making artificial fire for signaling others).

There is no organization or categorization used in the order of the entries, as showcased by the first page of the book, which contains two entries: one that describes how to use paper to polish steel and iron, and a second that describes how to preserve plants. Similarly, other pages have no logical order. For instance, on page 73, there are four entries, which in order, discuss a remedy for cancer, how to preserve iron from rust, a remedy for inflammation of the bowels, and an announcement warning the public against drinking spring water. Pybus delineates the start of a new topic by separating the title of each entry with two horizontal lines, over the top and bottom.

Many pictures are included in this manuscript, all hand-drawn using ink. For instance, on Page 186, a mechanical device that is utilized to detect the position of arbitrarily placed objects is drawn, and labeled with its components such as the "eyepiece", "index", and "pointer". As he notes in his entries, these figures are copied from published works. When there are several images on each page, Pybus labels them as Figure 1, Figure 2, and so on for clarity of understanding.

Authorship and Correspondents

There is no information that is known about William Pybus, other than that he wrote this manuscript. The Penn Libraries catalogue confirms that Pybus is the sole author of the manuscript, even though he does cite several of his correspondents that come from all around England. This is further evidenced by there only being a single handwriting style throughout the manuscript. It is unknown whether Pybus had other log books similar to this one. As he filled this book within a year, it may be reasonable to believe that he would have other log books that contained his thoughts in years prior or years to follow.

Correspondents

For most of the entries in this manuscript, Pybus cites a correspondent from whom he has learned about that particular invention, technique, or treatment. For instance, in his entry about unsafe spring water, he notes that “a correspondent of the Threurberg Chronicle” wrote that from personal experience, drinking the local spring water was unsafe. Furthermore, in other entries, he also cited where these correspondents are from, ranging from “Bristol” to “Liverpool” to several other known locations across Britain. Several of the cooking recipes that he includes also are from correspondents that he cites, whom he labeled as "respectable", such as in the entry for turnip bread on page 27. During this period, it was not uncommon to copy recipes from other more notable cookbooks and often served as a means to preserve recipes across generations. Furthermore, Pybus would often create criteria for the recipes he wrote down, including its overall cost, its utility, or its taste. This is a unique aspect of this manuscript, as many historical cookbooks lacked any extra insight other than the ingredients required.[7]

Material Analysis

Substrate

The book is crafted from coarse, uneven paper characteristic of the 19th century. Pybus did not construct the book himself but instead bought the empty book from a seller. The pages have shown evidence of yellowing in the past two centuries. There is some ink smudging from where Pybus was writing. However, the paper remains in quite good condition, with no pages ripped or left out.

Format and Binding

The book is considered an oversized book, with dimensions of 33 cm by 21 cm, which is inconvenient for carrying or transport, and is more fit to stay indoors as a mansucript that Pybus would return to each day. The book is a codex in folio format, and the page numbers in the original ink are only found on the verso side of the page. However, following the change in ownership to Edgar Fahs Smith or to the University of Pennsylvania, the pages were then labeled on both the recto and verso sides, possibly for convenience. Notably, these page numbers were written on the bottom, potentially because by this time it was more traditional to have page numbers written on the bottom of pages.

This mansucript does not contain a table of contents, and can be challenging to navigate due to the lack of landmarks across the pages. On each page, the left side of the page has an inch margin that is left empty, with a vertical inked line. Two horizontal lines stretch from the vertical margin to form a thin section where the title resides. This pattern is consistent for the entire manuscript. Topics in the span of several pages can range from medical treatments, to recipes, to inventions.

Book Use

Annotations/Marginalia

There is little marginalia in Pybus’s book, reflecting that Pybus was the sole contributor, and that the manuscript was meant only for personal reference. There is one annotation that is made on the inside of the front cover, noting that this book was itemized within the library as HS. Codex 2162. It is clear that this was from an owner that came after Pybus, as the writing seems to be graphite instead of ink.

The lack of marginalia also reinforces that this book was only used by Pybus. If the book was used as an educational tool or was passed around among several readers, often significant underlining, circling, or other handwriting present as footnotes would be seen.

Marks

There is a distinct lack of markings on the book, such as underlining, crossing out, or circling. Pybus seemed to have underlined his own notes occasionally, evident by the same type of ink being used, but these marks were few and far between, and was not a consistent pattern across the book. This suggests that the book was utilized just as a reference book or handbook for recipes, treating ailments, or inventions, and not as an educational tool or piece of literature that was reviewed in a critical fashion.

Significance and Provenance

William Pybus's recipe book from the early 19th century exemplifies the unique integration of culinary arts with the technological spirit of the time. This collection of written entries not only provides new recipes that caught Pybus's eye but also delves into the realms of scientific experimentation and inventive technologies. The inclusion of technical illustrations, such as detailed drawings that contain meticulous labels, within the book highlights its alignment with the era's growing emphasis on scientific understanding and mechanical innovation. By blending traditional knowledge of homecare with emerging scientific insights, Pybus's work is a testament to the period's intellectual expansion and curiosity, capturing the intersection of everyday kitchen wisdom with the transformative technological advances of the Industrial Revolution. This fusion in a recipe book format illustrates a broader cultural shift towards embracing scientific inquiry and technological progress in all facets of life, including the culinary arts.

Pybus's involvement in creating a book that integrates recipes with scientific and technological content marks a distinctive departure from the traditional recipe books of the early modern period, which were predominantly associated with women. This shift highlights changing gender and cultural norms during the early 19th century, providing a unique lens into the evolving and globalizing world of that era.

Provenance

The provenance of this book originates in 1932, when the Edgar Fahs Smith Fund took Smith’s large collection of rare books, papers, and collections, into Penn’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Smith was at the University of Pennsylvania for nearly forty years as an instructor, professor, and provost. Between 1816 and 1932, it can be inferred that Smith received this book from an independent seller, integrating it into his collection.

References

- ↑ Notaker, Henry. A History of Cookbooks: From Kitchen to Page over Seven Centuries, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2017. https://doi-org.proxy.library.upenn.edu/10.1525/9780520967281

- ↑ Wall, Wendy. Recipes for Thought: Knowledge and Taste in the Early Modern English Kitchen. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015.

- ↑ Madeline Shanahan. “‘Whipt with a Twig Rod’: Irish Manuscript Recipe Books as Sources for the Study of Culinary Material Culture, c. 1660 to 1830.” Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature, vol. 115C, 2015, pp. 197–218. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.3318/priac.2015.115.04.

- ↑ Kook, Kyunghee et al. “A Literature Review on the Recipes for Pheasant - Focus on Recipe Books from 1800's to 1990's -.” Journal of the Korean Society of Food Culture 26 (2011): 455-467.

- ↑ Barka, Ellen. Cookbooks as historical literature : a comparative study of 19th century cookbooks Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008.

- ↑ ALLEN, R.C. (2011), Why the industrial revolution was British: commerce, induced invention, and the scientific revolution†. The Economic History Review, 64: 357-384. https://doi-org.proxy.library.upenn.edu/10.1111/j.1468-0289.2010.00532.x

- ↑ Schmidt, Stephen. "What Manuscript Cookbooks Can Tell Us that Printed Cookbooks Do Not." Manuscript Cookbooks Survey, May 2015. https://www.manuscriptcookbookssurvey.org/essays/553/