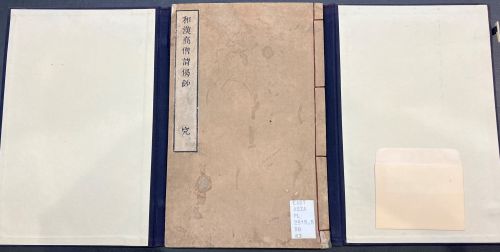

Wa-Kan kōsō shige shō

Wa-Kan kōsō shige shō (“Wa-Kan Eminent Monk’s Poems”) is a collection of poems credited to “Wa-Kan Eminent Monk” (和漢高僧) that was reprinted in the Bunsei Era of Japan. These poems have been reprinted through modern times, resulting in many editions, with this edition being printed in 1819 and more recent editions being printed as recently as 2006. This collection contains a total of 53 poems on various subjects from scenes in nature to principles of life and was printed with woodblock carvings. This particular edition was printed for a Japanese Zen Buddhist Temple.

Context in Japanese Literary History

Kanshi

This book is an example of kanshi, either Chinese poetry or Japanese poetry composed in Chinese. This form of poetry was the most popular of its time during the Heian period among the aristocrats in Japan because of their fluency in kanji. A popular style of kanshi included onji, which was composed with 5 or 7 syllables (onji) in 4 or 8 lines, with rhyming that followed a stringent guideline. Later, due to efforts by the Sorai school of Japanese Confusion scholarship to promote kanshi as well as changes in Japanese society, composition of such poems rose throughout the Edo period and peaked in the 19th century. This was helped by the aforementioned proliferation of woodblock printing capabilities at the time. Growing interest and accessibility for general audiences may explain the date of the woodblock production as well as the reprinting of this collection of kanshi. In modern and contemporary society, kanshi was been falling out of fashion, coinciding with less prevalent education in Chinese literature.

Features of the Book and its Use

Japanese Woodblock Printing

This book was printed in relief from woodblock carvings made by three woodcarvers. Woodblock printing was introduced to Japan in the eighth century and was practiced almost exclusively by Buddhist institutions. By the time the woodblocks for this book were made, woodblock printing had succeeded in making printed texts more accessible financially and practically, which coincided with an increase in Japan’s literacy rates in the late Edo period.[1] Woodblock printing, or Mokuhanga, was widely adopted across hundreds of publishers to keep up with the demand for re-printed books since each set of woodblocks could be reused.[2] Mokuhanga involved carving each character of the text into a block of wood usually around 2cm thick following the right to left and vertical reading convention. In this book, lines are separated with inked vertical lines with a total of 8 such lines on each page (16 per sheet). Water-based ink would be applied to the finished block to produce a print on sheet of paper which would be folded in half with the printed side facing outwards as exemplified in this book.

Copyright of Books

During the Edo period, publishers made a clear distinction between books with educational and more serious content generally for a more educated audience (shomotsu, 書物) and books with lighter and trendy content for general audiences (sōshi, 草紙). As a text printed for a Buddhist institution and containing Chinese poetery, this book would be considered shomotsu and as such is printed exclusively using “block kaisho” and using kanji characters. It lacks the colorful illustrations and extremely calligraphic “sōsho” lettering that were often a feature of sōshi, which were instead printed with kana.[3] Beyond differences in appearance and subject, this categorization had more implications for publishing rights in early-modern Japan. While on the (term for inside cover) of the book, the three woodcarvers are credited for their involvement in the production of the book, the ownership of the woodblocks was extended to also include ownership of intellectual rights and the content of the woodblocks. So it is likely that the publishing company that commissioned or purchased and stored the woodblocks for this book also owned the publishing rights to this book.

Fukurotoji Binding

This book is a Fukurotoji (袋綴じ), meaning a “bound-pocket book,” of Hanshi-bon ("half paper books") size. Among the bookbinding methods used in early-modern Japan, this binding method was usually dedicated to printed books and was by far the most commonly used. Like the other binding methods, content was printed on sheets twice the width of the final intended book size and folded in half individually and stacked. A distinguishing feature of the fukurotoji method is that the binding is sewn through the free edges opposite the fold, meaning that each sheet was only printed on one side before being folded and bound, producing an inaccessible namesake “pocket” in between.[1]

Along the centerfold of each sheet, in an area called the “pillar” (hashira/hanshin, 柱) indexing and page number information is printed to aid in navigation of the text, as is standard for the majority of books printed around this time. Additional information, including the author, title, publisher, and volume number was also sometimes included in this folded area. For instance, the hashira of the first two pages uniquely read “Catalog of Poems” followed by a “one” on the first page and a “two” on the second page. Navigating to these pages, a reader would indeed find a list of the poems included in this book.

Washi Paper and Cover Construction

The paper used for this book is extremely light and thin, resulting in a writing surface that is quite transparent. Despite the book’s age, the pages are well preserved and not significantly yellowed. With plant fibers being visible in some of the pages of the book, it seems that the paper used is a variety of washi (和紙), which is more durable than wood pulp paper. The use of such thin paper was enabled by the fukurotoji binding method, as duo-sided legibility was not necessary.

A similarly thin paper is used for the covers of this book without any of the common cover decorations of the time, and the title strip containing the "outside title" (gedai, 外題)[4] is a separate slip of paper glued onto the outside front cover. On the inside front cover, the "inside title" (naidai, 内題) is printed in significantly larger font of a different style. A distinction is made because the gedai and naidai did not always match, and in such cases the “unified title” (tôitsu shome, 統一書名) by which the book would be known would align with the gedai. This book has an additional line of publication information printed above the naidai which reads “Bunsei tsuchinotō jūin” (“Bunsei era, yin earth rabbit year reprint,” meaning that this is an 1819 reprint).

The back cover construction is the same as the front, without any additional information on the outside. The inside back cover contains the colophon (kanki/okutsuke, 刊記) which usually holds publishing information which can include the names of the author, publisher, hanmoto (owner of the woodblocks/copyright), the illustrator(s), block-carver(s), printer(s), as well as their addresses, and the year the woodblocks were made. For this book, the colophon contains the year the woodblocks were produced (“Bunka era, the fourteenth/yin fire ox year, Spring third month,” referring to March of 1817) and the names of the three block-carvers. Additional information includes text that approximately reads “gifted to Kaiō Zen'in (name of a Zen/Buddhist temple)” along with “Shinshū Komoro” which might mean the “Komoro domain” of the old “Shinano Province.”

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Kazuko Hioki. Characteristics of Japanese Block Printed Books in the Edo Period: 1603–1867 (2009): https://cool.culturalheritage.org/coolaic/sg/bpg/annual/v28/bpga28-06.pdf

- ↑ Andrew T. Kamei-Dyche. The History of Books and Print Culture in Japan: The State of the Discipline. Book History, Vol. 14 (2011), pp. 270-304: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41306539

- ↑ Kaneko Takaaki. The Printing Blocks of Woodblock-printed Books: https://pulverer.si.edu/node/1217

- ↑ Glossary of Japanese book terminology: https://samurai-archives.com/wiki/Glossary_of_Japanese_book_terminology