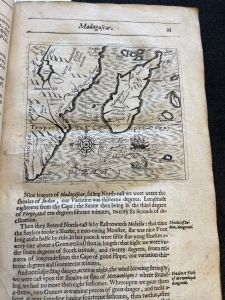

Thomas Herbert's Account of Africa, Persia, and Beyond

A Relation of Some Yeares Travaile, published in 1634, epitomizes the genre of travel literature that developed as English colonial expansion intensified in the subsequent decades. Written by Thomas Herbert, the book delivers an extensive and meticulous account of his journeys through Persia, East Africa, and adjacent islands. It is particularly noted for its exploration of foreign cultures, languages, and traditions, capturing regions that were largely unknown to his contemporaries in England. Herbert's work provides a critical insight into the implicit and explicit biases of the era, reflecting perceptions of the "other" – peoples and places beyond familiar territories. The book details unfamiliar traditions, includes translations of numerous local terms, and describes the geographical landscapes with detailed engravings, including prints of indigenous people. It is crucial to acknowledge and analyze the inherent biases in these descriptions, as they shape a constructed perception of native peoples' culture, customs, and appearance.

-

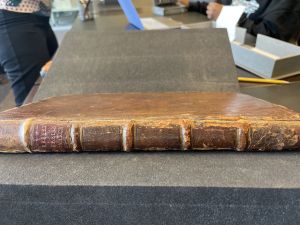

Front Cover of Thomas Herbert's A Relation of Some Yeares Travaile.

-

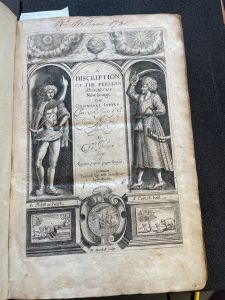

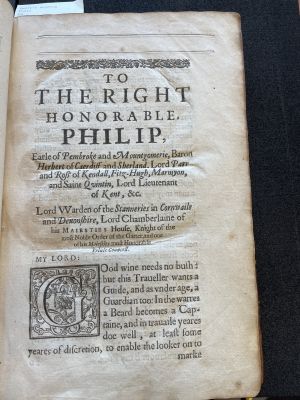

Title Page of Thomas Herbert's A Relation of Some Yeares Travaile.

Overview of A Relation of Some Yeares Travaile

Thomas Herbert: A Historian's Journey

Thomas Herbert was a historian and courtier to King Charles I. This book was initially part of a diplomatic mission led by Sir Dodmore Cotton to Persia.[1]However, following the mission's failure due to Cotton's death, Herbert continued to travel and gather information across the region[1]. He then went on to publish his observations in 1634 which was later expanded and republished in 1638. The second edition became a significant success and was quickly translated into Dutch and French, indicating the book's widespread appeal and impact on the European audience[1]. It is noteworthy that the book was translated into specific languages rather than Spanish or German, possibly reflecting strategic choices. This selection may stem from Britain viewing these nations as its main competitors in colonizing Africa, using the translations to assert dominance in travel literature. Alternatively, the choice could be motivated by English writers aiming to maximize interest and support for their colonial missions abroad, thereby accelerating the colonization process.

Dedication

In the dedication section of the book, Herbert acknowledges Philip Herbert, the 4th Earl of Pembroke, a prominent and influential figure at the English Court under James I. Known for his sharp intellect, craftiness, and volatile temper, Philip quickly rose to prominence, partly due to his affinity for hunting, which endeared him to King James I.[2] His strategic marriage to Susan de Vere connected him with the influential Cecil family, enhancing his position at court. Although not overly active politically, serving as a Member of Parliament for Glamorgan and later as Lord Chamberlain under Charles I,[2] Philip was deeply engaged in the arts, sponsoring artists such as Shakespeare and Van Dyck. Additionally, his memberships in the Virginia Company and the West India Company underscored his keen interest in expanding England's global power, which is likely a key reason Herbert (Thomas) dedicated the book to him. Philip’s navigation of court politics and significant cultural contributions have left an enduring impact on the English aristocracy. He passed away in 1650.[2]

Literary Genre and Cultural Impact

In Literature, Travel, and Colonial Writing in the English Renaissance, Andrew Hadfield highlights the multifaceted role of travel writing during the late 16th and early 17th centuries, emphasizing its link with political and ideological movements of the era. Travel writing not only served to document geographical and cultural information but also acted as a medium for political commentary and advocacy for colonial expansion.[3] Authors like Thomas Herbert used their narratives to influence England's political landscape, promoting ideas that aligned with their beliefs. Travel writing was instrumental in reevaluating personal and national identities. These writings challenged cultural assumptions by introducing readers to the “magnificent other.” Illustrators, like William Marshall, enhanced these works with engravings that complemented the texts' “grandeur.”[3] In the 16th and early seventeenth-century travel writing wasn't strictly defined. Many of these writings often exhibited a Eurocentric view, evaluating and judging foreign cultures through European standards.[3] This strongly influenced political and cultural attitudes toward colonization and interactions with non-European societies.[3]

Key Contributors to A Relation of Some Yeares Travaile

The Printers Behind the Pages

William Stansby

William Stansby was an influential printer in early Stuart London, born on July 8, 1572, in Exeter as the third of fourteen children to Richard Stansby who was a master cutler.[4] His journey in printing began when he was an apprentice to John Windet at the age of eighteen.[4] After gaining his freedom from Windet, Stansby continued working at his master’s shop at the Cross Keys until Windet's death in 1610.[5] He then took over the shop and became a master printer himself. His business acumen quickly developed as he navigated through complicated guild regulations. Despite some challenges, Stansby's press was highly regarded, as evidenced by his involvement in high-profile projects and the continuous operation of his printing house until his death in September 1638.[4] His interactions with notable contemporaries like Richard Bishop, who purchased his printing materials, and William J Butler, from whom he acquired copyrights, underscored his pivotal role in the London book trade.[5]

Jacob Bloome

Jacob Bloome, also recorded under variations like Bloom or Bloome, was an apprentice to Ralph Mabbe in 1611 before eventually succeeding him.[6] The variability in the spelling of Jacob’s surname, similar to the listings of Mabbe as Mabb, suggests that there were common inconsistencies in record-keeping of the time. Bloome’s career spanned several trades, including book selling, cartography, and the sale of maps.[6] His family background, with connections to bookbinding and step-relations like George Edwards Sr, further situates him within a network of print and book trade professionals.[6]

Artistic Mastery and Literary Contributions of William Marshall

William Marshall was an early English engraver active between 1617 and 1649, known for his contributions to the literary and historical significance of the works he illustrated as well as the artistic quality of his engravings.[7] Marshall was part of the first generation of native-born English engravers at a time when the field was dominated by Flemish and Dutch artists associated with prominent figures like Rubens and Van Dyck.[8] Marshall was considered a methodical but lackluster worker, but his work is historically and biographically important due to the significant literary figures and valuable books he was associated with.[8] He had the distinct privilege of engraving frontispieces for renowned authors and their works, such as Sir Thomas Browne’s Religio Medici, Herrick’s Hesperides, and the Eikon Basilike.[7] Marshall also created portraits from the life of notable individuals like John Milton and John Donne.[7] His contributions helped lay the groundwork for a growing British school of engraving, which flourished in artistic achievement in the subsequent generation with engravers like William Faithorne and David Loggan.[8] Despite his prolific career, little is known about his personal life. Marshall curated the essential visual elements of this book, which often convey the most crucial information to the reader. The frontispiece, featuring elaborate and highly detailed characters and scenes, immediately captivates the reader with its grandeur. The subsequent engravings, similarly impressive, have remarkably withstood the test of time, remaining clear despite centuries of wear.

-

Frontispiece created by William Marshall.

-

Engraving of East India Pegu.

-

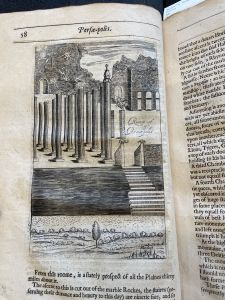

Engraving of Persepolis.

-

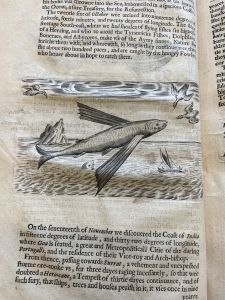

Engraving of a Flying Fish.

-

Engraving of an East Indian.

-

Engraving of a Manta Ray.

The Collaborative Craft of Bookmaking

The creation of this book was a meticulous and complex process. Thomas Herbert needed to specify the fonts, sizing, spacing, and ornamental styles to both Stansby and Bloome. He also needed to plan the layout for the woodcut engravings, integrating them seamlessly within the text. This is where William Marshall's expertise was crucial; Herbert had to convey the landscapes, animals, foliage, and people he encountered during his travels for Marshall to illustrate accurately. Producing this book was a challenging endeavor and required careful collaboration among many different subjects.

Physical Analysis

Substrate and Binding

The book is bound in what appears to be its original leather binding, likely made from cow or sheep’s leather, showing centuries of wear with expected cracking and peeling yet still in great condition. The spine features an engraving of the author’s last name and an abbreviated title, with small ridges indicating the binding method. The pages, made from linen, resemble an old dollar bill and are crumpled and discolored with a slightly funky, moth-ball aroma. Despite minor restorative efforts by Penn, such as gluing and cleaning to preserve the binding and contents, the leather and the very intact flyleaves remain largely original. An interesting aspect of the book is the frontispiece, which is crafted from a different type of paper than the rest, as indicated by marginal differences in the width of two striating lines observed under a flashlight, suggesting the paper was sourced from elsewhere.

Platform

The book is printed on broadside paper in folio format. Each sheet is folded once and then stacked on top of each other. A consistent watermark, depicting what appears to be fruit, grapes, and spherical objects on a scale, is present on nearly all pages. The watermarks have been carefully documented in a vast database. In the database, we can see many of the ornamental head-piece’s Stansby used. For example, in the epigraph, Stansby uses one with a wolf’s head in the middle which matches the database. We can also compare many of the ornamental large letters from the book that matches exactly to the ones used in the book from the database

This book is a collection of observations about specific regions, documenting customs, language, and geographical features. It is designed for readers to easily navigate through sections of interest rather than reading from front to back. Each paragraph is summarized in the margins with bold one to two-word descriptors, allowing readers to quickly scan and choose whether to delve deeper into the text or continue browsing other sections that catch their interest. This format invites readers to explore the book in a nonlinear fashion, focusing on topics that specifically interest them.

-

Margin information can be seen in small print on the right

-

Watermark illuminated using flashlight

Significance

Thomas Herbert's book, "A Relation of Some Yeares Travaile," published in 1634, is a significant piece of early travel literature linked closely with the English efforts to expand their power overseas. This book gives us a detailed look at distant lands like Persia and East Africa, places most English people at the time knew little about. Herbert wrote about the people, their languages, and the landscapes of these areas, but his writing also shows the typical misunderstandings and biases Europeans had about other cultures during that time.

The book includes beautiful illustrations that help bring Herbert’s descriptions to life, thanks to the efforts of artists and printers like William Marshall and William Stansby. It’s also dedicated to influential figures like Philip Herbert, who played a big part in England's colonial ambitions. By exploring this book, we can see how travel stories from centuries ago helped shape the ideas and attitudes of Europeans about the world beyond their borders. This makes Herbert's work an important tool for understanding the role literature played in the history of European expansion.

Sources & Citations

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 “History of Parliament Online.” HERBERT, Sir Philip (1584-1650), of Wilton House, Wilts.; Later of Enfield House, Enfield, Mdx. and The Cockpit, Westminster. | History of Parliament Online, www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1604-1629/member/herbert-sir-philip-1584-1650. Accessed 11 May 2024.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Hadfield, Andrew. Literature, Travel, and Colonial Writing in the English Renaissance, 1545-1625, Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 1999. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.proxy.library.upenn.edu/lib/upenn-ebooks/detail.action?docID=430908

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 “A Brief Biographical Sketch of William Stansby.” Stansby-Bio.Html: A Brief Biographical Sketch of William Stansby, 4 June 2005, www2.iath.virginia.edu/gants/stansby-bio.html.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 British Book Trade Index, bbti.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/search/?query=William%2BStansby%2B. Accessed 11 May 2024

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 British Book Trade Index, bbti.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/search/?query=Jacob%2BBloom. Accessed 11 May 2024.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 “William Marshall - National Portrait Gallery.” Person - National Portrait Gallery, www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/person/mp13298/william-marshall?role=art&_gl=1*1g0g8x3*_up*MQ..*_ga*MTgyMTYyMzc5Ny4xNzE1NTYzMDcz*_ga_3D53N72CHJ*MTcxNTU2MzA3My4xLjAuMTcxNTU2MzA3My4wLjAuMA.. Accessed 12 May 2024.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 William Marshall - Frontispiece to the Holy State - Art of the Print, www.artoftheprint.com/artistpages/marshall_william_frontispiece_holy_state.html. Accessed 12 May 2024.