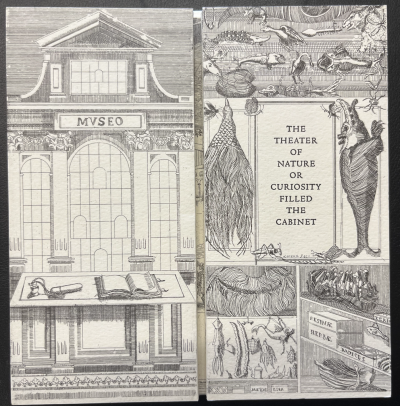

The theater of nature, or, Curiosity filled the cabinet

“The theater of nature, or, Curiosity filled the cabinet” is an artist’s book created by Angela Lorenz in 2002 as a facsimile, or trade copy, of an original handmade 1999 edition. Both editions were printed at the Stamperia Valdonega of Verona, and the 2002 facsimile is now housed in the University of Pennsylvania’s Kislak Center for Special Collections. This book examines the rise and decline of cabinets of curiosities using two mounted accordion folds with work on both sides. The book depicts Lorenz’s own hand drawn copper plate etchings, which use engravings of the earliest museums in Europe as a reference. A rhyming poem is included on the inside and is accompanied by nine watercolor paintings featuring various oddities referenced in 16th and 17th century manuscripts commissioned by collectors Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522-1605) and by Manfredo Settala (1600-1680).

Background

Angela Lorenz

Angela Lorenz (born 1965) is a book artist from Boston, Massachusetts who has been producing her work in Bologna, Italy since 1989.[1] She is a graduate of Brown University, earning her bachelor’s degree in Fine Art and Semiotics, accompanied by classes at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) and the University of Bologna. She has been featured in prestigious museums such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and her work has appeared in publications such as La Repubblica, the Boston Globe, and the Benezit Dictionary of Artists published by Oxford University Press.[1] Her basis for her work is research using nonfiction and archival materials and combining them with different visual arts techniques such as textiles and bookbinding. While the majority of her work is intended for long term preservation, she will also use perishable elements if it helps communicate the meaning. Often, her works include humor, mnemonics, and data visualization, and her most frequent topics of interest include history, literature, archaeology, and architecture. Lorenz was originally going to investigate the presence of manufactured and fake oddities in Ulisse Aldrovandi’s remaining cabinet of curiosity materials housed in Aldrovandi Museum at the University of Bologna. However, particularly after reading the work of Stanford University Professor of Italian History and History of Science Paula Findlen, the project expanded to museology, or the study of museums, in general.[1][2]

Historical Context

Cabinets of curiosities, also known as wonder rooms or theaters of nature, were rooms housing extensive collections of objects that were often arranged according to relationship with one another rather than systematized boundaries.[2] The cabinets’ prevalence began in the 16th century in Renaissance Europe, extending through the late 17th century. The types of objects typically found in these rooms can range from books, to preserved animals, to historical artifacts from foreign nations. In 1587, one suggestion of three requisite object types for a cabinet of curiosity were material works of art, "curious items from home or abroad,” and "antlers, horns, claws, feathers and other things belonging to strange and curious animals.”[3] These collections were often the precursors to museums. In addition to art and natural objects, many wonders were faked, particularly in order to produce supposedly new and strange animals such as a frog with a lizard’s tail and a fish’s teeth.[4]

The inconsistent nature of these cabinets allowed the collector to display their objects in an arrangement more focused on the object’s personal network of relationships rather than a predetermined system, positioning them in the same space as similar objects in order to link them and create meaning.[5] To the contemporary eye, the objects within these rooms could be categorized as belonging to natural history, archaeology, art, biological rarities, and antiquities. To better understand the unsystematic means of organizing: it was only after the time period of the cabinets of curiosities had ended that the Swedish naturalist, Carl Linnaeus, established in his 1735 work Systema Naturae the three major kingdom classifications of “Animal, Vegetable, and Mineral.”[6] Prior to this, the boundaries of the natural world were blurred.

Cabinets of curiosities were not just personal collections, but were meant to be displayed. These rooms could either serve the social function of showing off hierarchy depending on the amount of wealth necessary to amass such a collection, or could be simply representative of the naturalist or humanist scholar dedicated to its study.[7] Literary scholar Stephen Greenblatt identifies the responses of wonder and resonance to be the two main outcomes spurred by these cabinets, stating that wonder is the object’s power “to stop the viewer in his or her tracks, to convey an arresting sense of uniqueness, to evoke an exalted attention,” and that resonance is the object’s power “to reach out beyond its formal boundaries to a larger world, to evoke in the viewer the complex, dynamic cultural forces from which it has emerged.”[8] These collections were also intent on inspiring wonder not just through the types of objects, but in the access of objects themselves. The architecture of these cabinets was very open, allowing every object to be visible at once, but incredibly crowded, often overwhelming or wondrous to the viewer.

Both Ulisse Aldrovandi and Manfredo Settala’s work inspired Lorenz in the painting of the watercolors in the artist’s book. Aldrovandi was an Italian intellectual and a curiosity collector who eventually became the first professor of natural history at the University of Bologna.[9] Manfredo Settala was another Italian curiosity collector, credited with founding the Settala Museum in Milan, which is considered among the world’s earliest natural history museums.[10] Both men compiled manuscripts, Aldrovandi’s Tavole di animali, and Settala’s Catalogo di diversi disegni, illustrating their wondrous objects, from which Lorenz pulled for this piece.[11][12]

These objects began to lose their value in the eyes of other naturalists and scientific philosophers around the beginning of the eighteenth century. With the beginning of the Enlightenment period, more and more philosophers turned their attention towards discovering the rules of nature and the broader environment, rather than finding only exceptions to these rules, which were soon deemed as blemishes to uniformity in nature. Particular emphasis was placed on the presence of forgeries, which made the entirety of these cabinets subject to criticism and accusations of being unscientific.[2]

Material Analysis

Substrate

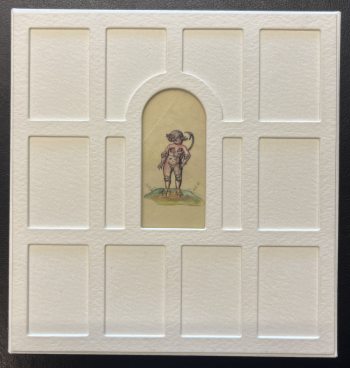

The body and cover of this artist’s book contains acid-free paper produced by Cartiere Fedrigoni, an Italian paper manufacturer. The cover of this 2002 edition has a small glass pane inside the front, and the cover unfolds to stand on its own to mimic a magic lantern. The book itself has copper plate etching and watercolors prints, including a poem. It measures 11.3″ x 11.3″ and 26″ x 11.3″ x 24″ when displayed upright. There are 5000 copies.

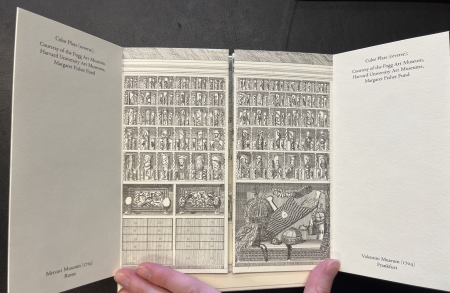

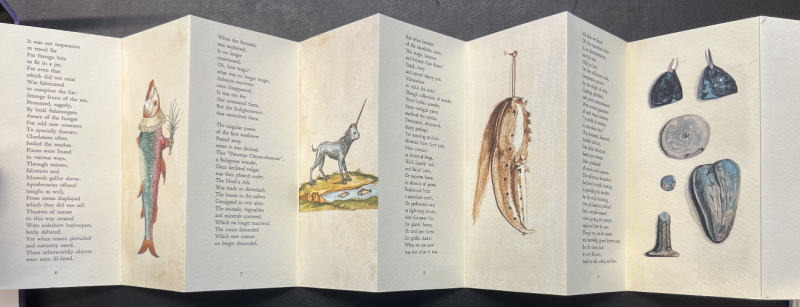

When the body of the book is taken out of the folding cover, the front splits into two accordion folds. If the two half pages are opened in tandem, the reader can enter a simulated cabinet, progressing through its rooms until reaching the end print. When viewed from the back, the watercolor print pages are numbered in order to facilitate reading the poem. In this orientation, the right side accordion fold is read left to right, followed by the left accordion fold, read left to right.

Copper Plate Etchings

Reproduced in this edition are the prints from the artist’s eleven hand drawn copper plate etchings. These black and white etchings reference the earliest museums in Europe, which, read in order from the beginning of the front accordion fold to the end are the Mercati museum (1719) in Rome, the Valentini Museum (1704) in Frankfurt, the Levin Museum (1706) in Amsterdam, the Imperato Museum (1599) in Naples, the Cospi Museum (1677) in Bologna, and the Vindobonensi library (1700) in Vienna. The etchings are intricate, and designed to mimic the wonder and overwhelm visitors feel when stepping into a cabinet, showing the curiosities withdrawing into the distance.

Watercolor Paintings

These nine watercolor illustrations are taken from Aldrovandi’s Tavole di animali, and Settala’s Catalogo di diversi disegni and reproduced by the artist by hand. Some of the watercolors are referenced in the poem, such as the fish in Figure 4, stating “Strange fruits of the sea, / Presented, eagerly, / By local fishmongers / Aware of the hunger / For odd new creatures / To specially feature.” This is a reference to the fakes that can be found in cabinets of curiosities. Another watercolor illustration is of a “lobster claw flute,” depicted in Figure 5.

Text

The poem is printed in the typeface “Centaur” as a nod to the mythical beast. The poem, interspersed with the watercolor illustrations, explores the history of cabinets of curiosities ranging from, as the book states, “Hellenistic Greece to the Enlightenment,” through to their disuse. The poem is rhyming and 900 words long. It begins by discussing how cabinets opened with the new age of curiosity in the Renaissance, and then discusses how the objects were arranged to inspire wonder, what types of objects could be found, and how the motivations of the scientists and nobles who collected these objects was often a different kind of categorization: “where art and nature / suffered no schism.” The poem continues to discuss how the objects came to be in possession, such as with foreign travel, voluntary submissions of forgeries, through working class and enslaved people, and businesses. The poem describes the fall of the cabinets, stating that the cabinets became “sideshow burlesques, / hotly debated,” due to the presence of forgeries and that reason soon overtook curiosity. The remains of these collections are either sparse or only in the written documentation of the collection catalogs and prints. These objects were divided into more systematized and narrow categories to further scientific learning. The poem concludes by maintaining that what was gained from the cabinets of curiosities was more than just science, despite current attitudes.

Differences Between the 1999 and 2002 Editions

The 2002 trade copy was streamlined for production and preservation in order to house it in museum and archive standards. This meant that some of the substrate features of the handmade 1999 edition were lost. The 1999 edition had several symbolic elements that Lorenz had incorporated into the artist’s book to tie it more closely to cabinets of curiosities. In a note included within the artist’s book, Lorenz specifically stated that she wanted to nod towards the “animal, vegetable, and mineral.” The original cover had window panes made of hand-cut pieces of mica, which is heat resistant to mimic the previous museum use of asbestos, to represent the mineral. Additionally, the original used calendula flowers to dye the paper to reference the vegetable. As for the animal, Lorenz bound the original work in vellum. The outside case closed with the use of magnets, which were secured by leather straps. These straps had stitching that formed the letter “u” in reference to Ulisse Aldrovandi. When oriented as a magic lantern box, the “Crakow man” is visible on the front of the box and can be illuminated. Finally, the poem was non-electrically printed in moveable type. While the 2002 copy does not have these features, echoes of them linger in the current substrate.

Significance

Because this artist’s book was made in the 21st century, its significance to society is hard to judge. However, this piece has joined the tradition of artist’s books, making an impact on the literary and artistic world, questioning social constructs such as the form of the book and how it interacts with and imparts knowledge to the reader. The original 1999 version of this artist’s book, as stated on the copy of this 2002 trade edition, has been shown in exhibition at the New York Public Library, at MASS MoCA, and at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Additionally, the original work can be found in other public collections such as the Fogg Art Museum and the Library and Research Center of the National Gallery of Art in Washington.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Lorenz, Angela. “Angela Lorenz Artists Books.” Accessed May 1, 2024. http://www.angelalorenzartistsbooks.com/

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Findlen, Paula. Possessing Nature: Museums, Collecting, and Scientific Culture in Early Modern Italy. California: University of California Press, 1994. https://doi-org.proxy.library.upenn.edu/10.1525/9780520917781

- ↑ Gutfleish, B., and J. Menzhausen, "How a Kunstkammer Should Be Formed", Journal of the History of Collections, Vol I (1989): p. 11.

- ↑ Lorenz, Angela. “48. THE THEATER OF NATURE OR CURIOSITY FILLED THE CABINET – TRADE EDITION.” Angelonium. Accessed May 1, 2024. https://angelonium.com/48-the-theater-of-nature-trade-edition/

- ↑ Van Reenen, Catherine. “Toward a Media History of the (Digital?) Wunderkammer: A Case Study of Samuel Quiccheberg’s 1565 Proposal for an Ideal Wunderkammer.” Concordia University. April 2018. https://spectrum.library.concordia.ca/id/eprint/983796/1/vanReenen_MA_F2018.pdf

- ↑ Linnaeus, Carl. Systema naturae per regna tria naturae: secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin) (10th ed.). Stockholm: Laurentius Salvius, 1758.

- ↑ Impey, MacGregor, and Arthur Oliver. The Origins of Museums: The Cabinet of Curiosities in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century Europe. Oxford University Press, 2001. p. 737.

- ↑ Greenblatt, Stephen. “Chapter 3: Resonance and Wonder.” in Resonance and Wonder, pg 42-56. 1991. http://stephengreenblatt.com/sites/default/files/Karp-Levine.pdf

- ↑ Barton, W.M. “Aldrovandi, Ulisse.” In: Encyclopedia of Renaissance Philosophy. Springer (2016), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-02848-4_890-1

- ↑ Squizzato, Alessandra. "Settala, Manfredo." In Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Volume 92: Semino–Sisto IV (in Italian). Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana. 2018. ISBN 978-8-81200032-6.

- ↑ Aldrovandi, Ulisse. Tavole di animali, University of Bologna library: BUB (bologna universität bibliothek). t. VI, cc. 42, 49, 59, 108 t. VII, Cc. 43, 121

- ↑ Settala, Manfredo. Catalogo di diversi disegni. Biblioteca Estense of Modena.