The Xerox Book

The Xerox Book was first published in 1968 and is generally classified as an Artists' book. More specifically, though, it is a "book-as-exhibition." Conceived by Seth Siegelaub and co-published by Siegelaub and Jack Wendler, it contains the works of 7 different artists: Carl Andre, Robert Barry, Douglas Huebler, Joseph Kosuth, Sol Lewitt, Robert Morris, Lawrence Weiner, who were invited to respond in a conceptual manner to the Xerox machine. Rather than a documentation of the art, Siegelaub had intended it to be both the exhibition and the art itself. He also hoped to reproduce all copies through xerography, but high costs forced him to print them as lithographic offsets of the original Xeroxes instead.[1]

Background

Historical Context

The Conceptual Art Movement

The Xerox Book was published as part of the Conceptual Art movement, between the late 1960s and early 1970s.Conceptual Art is defined by art historian Alexander Alberro through four main characteristics:[2]

- 1. De-emphasization of art's hierachical value system

- 2. Dematerialization of the the actual work of art

- 3. De-aestheticization of work

- 4. Problematizes placement

Essentially, conceptual artists believed that the fundamental aspect of art lay not in the final product as typically exhibited in galleries, but rather in the idea behind the work. [3] They were also drawn to the anonymity of bureaucratic and scientific formats and distrusted the excessive personality within the styles of artists like Jackson Pollock.[2] As such, Siegelaub's interest in a bureaucratic tool, the Xerox machine, was no surprise.

The Xerox Machine

The significance and impact of the Xerox machine evidently plays a large part in the Xerox Book. Invented in 1939 by Chester Carlson (1906-1968) and first manufactured for office copying in 1960, the Xerox machine (Haloid XeroX 914 Office Copier) relies on a process called xerography, where the interactions between light, a photoreceptor (a thin coating of selenium around an aluminum cylinder), and toner (black pigment) produces a permanent mirror image of the original document on a separate sheet of paper.[4]. In a book on this invention, the author, David Owens, argues that "copying is the engine of civilization: culture is behavior duplicated." He cites four major milestones in copying history that had resounding ramifications on human's way of life, namely language, writing, printing (which, technically speaking, is an act of duplication as it relies on transference to a printing plate to make prints), and finally, photocopying. The machine possessing this fourth technology was simple enough for a child to operate, and gave "ordinary people an extraordinary means of preserving and sharing information," allowing for their "rapid exchange of complicated ideas." Within the increasingly dominant corporate culture of the 20th century, this presented itself in was like reproducing invoices and providing documents for each person rather than circulating them, which accelerated the pace of business operations. [5]

Though the Xerox machine was expensive to produce, weighed 648 pounds, thus only leased to businesses, and was often imperfect in its copies (ink smudges, incomplete images, and more) and prone to malfunction, it quickly became "the most successful product ever marketed in America" according to Fortune[6] because people quickly believed that they couldn't live without it. This particular achievement could also be attributed to the multitude of ads that soon flooded the public consciousness. One of the most famous was in major business magazines in 1963, which asked readers to differentiate between a genuine Picasso and its Xerox. Votes showed they couldn't.[5]

It was within such a climate, less than a decade after the establishment of the Xerox machine that Siegelaub conceived and published his Xerox Book. Given that the Conceptual Art movement were drawn to the impersonal documents of bureaucratic culture, its championing tool would be an intriguing experimentation to create fine art. Conceptual artists also believed the appreciation of art to be a democratic engagement; xerography, a technology that improved communication for the ordinary people, would again serve as the perfect mode for their works. Further, this movement prioritized the aesthetic idea over its material manifestation. The Picasso ad only affirms that the Xerox was a viable and efficient means to access art.

Seth Siegelaub

- Main article: Seth Siegelaub

The mastermind behind the Xerox Book, Seth Siegelaub (1941 – 2013), was already a well-established art dealer, curator, and publisher in New York. Throughout the 1960s and 70s, he organized a multitude of exhibitions both in the US and Europe, playing a seminal role in the promotion of Conceptual Art. [3] The element that distinguished Siegelaub's from his peers during this time lay in the unique approach he took to exhibitions, often closely collaborating with artists in order to emphasize the core beliefs behind the movement. Since Alberro's fourth pillar (as discussed in The Conceptual Art Movement) relates to a non-gallery placement, Siegelaub pioneered new settings and formats in which art could materialize. The Xerox Book was Siegelaub's first endeavor into the "book-as-exhibition" or artist's book format, but not his last. In November of the same year, he "exhibited" the work of Douglas Huebler, one of the artists featured in the Xerox Book. Titled November 1968, this was a site-specific sculpture exhibition that only existed through its documentation (photographs of non-meaningful locations, marked street maps) printed in a book; in other words, the art only could be seen through the book.[2]

Creation Process

Siegelaub invited seven influential Conceptual artists, several with whom he had previously collaborated, to create and exhibit their work, with only two requirements: one, it had respond to the Xerox machine; two, the 25 pages had to be the art rather than a documentation of art.[7] All artists chose to utilize the Xerox machine as a mode of creation, with some submitting 25 pages of their work and with others, such as Andre, instructing the publishers to help with the execution. Originally, Siegelaub and Wendler had planned to photocopy each page to create every copy for an additional layer of self-reflexivity. However, Wendler recalls in an interview that the overall price would come out to ten to fifteen thousand dollars per piece, which was too hefty a price to publish any book. Thus, they settled on the traditional printing method of offset lithography for the first edition, which perhaps highlights the reason that xerography never took over as a book-printing technology. Each copy than sold for 20 dollars.[8] This process also questions the notion of authorship. Though the seven artists each came up with their individual ideas, Siegelaub conceived, designed, and orchestrated the overall book. If this book were to be classified as an artist's book, Siegelaub could be considered the author and the artist.

Editions

Siegelaub and Wendler only ever published one edition of 1000 copies in 1968. In December 2015, Roma Publications, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, De Appel arts centre, and Egress Foundation collaborated to publish a second edition. [9] There is no information on the number of copies within the second edition.

Material Analysis

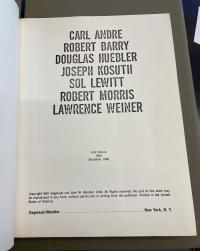

This particular copy resides in The Kislak Center for Special Collections at the University of Pennsylvania, and, due to the lack of a formal title, it is catalogued as Carl Andre, Robert Barry, Douglas Huebler, Joseph Kosuth, Sol Lewitt, Robert Morris, Lawrence Weiner. The entry lists its alternative name as The Xerox Book, categorizes it as an "Artists' Book," and notes that it is a first edition, published in 1968.

Structure

- Cover

- Like other copies, the cover of the book is plain white, with no title or illustrations, and paperback, made with some sort of heavier acid-free paper. It is also protected by a plastic cover, though this is most likely a later addition from Kislak to preserve the book. Despite the relative fragility of the paper cover, it remains in good shape for a 54-year-old book, with little wear and only some slight yellowing around the edges. The only exterior text lies on the spine—the last names of contributing artists and publishers are listed alphabetically on the top and bottom respectively.

- Binding

- The book is adhesive bound, with evidence of discoloration from the glue on inner edges of the cover flap and clumping on the spine. Since there is no pastedown, closer inspection shows notches in the spine where hot glue would have penetrated the spine of the book and face-trimming on the three sides of the paper, suggesting the book to have been bound through "perfect binding" (See: Bookbinding, Thermally activated binding), a popular method for paperbacks during this time. The sectioned sides of the book may also point to traditional gatherings of 8 leaves (octavos); however, the paper is letter size (8.5 inches by 11 inches) as opposed to the typically smaller octavos, and the gatherings are hard to discern towards the middle and end.

- Paper and Print Quality

- The interior paper is thin and slightly transparent, with ink from the recto visible on the verso. The ink-bleeding may have led Siegelaub to print all content on the recto, though the choice could have also been a creative one, mimicking the single-sided photocopying of the Xerox machine. Furthermore, though Siegelaub had intended to reproduce the book with the Xerox machine, photocopying proved financially unfeasible. All copies in the first edition were thus printed by offset lithography.

Overall, the plain exterior, lack of title, inexpensive cover and binding, and fragile paper suggest a lack of importance in the book as an object; rather, this codex form only serves as a platform to widely disseminate its interior ideas.

Marginalia and Readership

The pages in this copy show little wear, with no obvious creases nor environmental damage. It also remains relatively free of marginalia, with only faint pencil markings on the inside of the back cover. Besides the current Kislak catalog code in the middle, there is a circled "389," which suggests this to be the 389th copy in the first edition. Since, the writing of the number “8” originates at a different spot, and the pencil shade is different than the Kislak code, indicating that perhaps the seller or even the publisher had made this notation. There is also a small slip of paper stuck between the back cover and the last page with the price of $450. Interestingly, each copy in the first edition had originally sold for $20 in 1968.[2] Regardless of whether Kislak had obtained the book recently or in 1968, the dramatic increase in price and the first edition's classification as a collector’s item soon after publication may suggest an inability of even Conceptual Art to defy commodification. Furthermore, the well-preserved state of this copy suggests it was acquired by Kislak first-hand, or at least suggests scant readership, failing, as Siegelaub had intended, to disseminate amongst a wide audience beyond collectors.

Content

- Title page

- The Xerox Book lacks any introductory text to the following works besides a title page (p3). This title page resembles one of a modern book, listing the artists in alphabetical order in the center, providing the publishing date, location, and publishers in a smaller font near the bottom, and stating the copy as one of 1000 in the first edition. The scant information emphasizes the importance of its content, and further, the following pages as stand-alone works. This page, in resembling any cheap paperback, also adds an interesting dimension to the work as a whole: one on hand, it establishes the ability of the physical codex to be an exhibition, to be the art; on the other hand, the physical object itself is widely available, an interchangeable copy, and only a vessel for a greater idea.

- Artwork

All of the pages utilize the Xerox machine as a means of creating art, and as such, each work, totaling 25 pages, is bound within the standard 8.5 by 11 format and presented in black and white. They also all fall under Conceptual Art, emphasizing the idea over the physical, and provoke various questions on topics including the nature of the book, the Xerox machine, and the relationship between the art, the artist, the producer, and the audience.

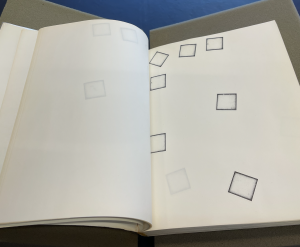

- Carl Andre

- Carl Andre (born 1935) is the first artist to show up in the alphabetically-organized Xerox Book. An American Minimalist sculptor and poet, he is most known for his use of materials such as bricks or stone tiles to create simple geometric sculptures. [10] This theme is evident in his 25 pages, which involves a progression of squares, starting from one square on the first page, to a total of 25 on the 25th page. Jack Wendler remembers that Andre had been in Rome during the time of the book's production and had asked him and Siegelaub to create the work for him. Following Andre's directions, they started from the top left and dropped one-by-one inch cubes on the Xerox machine to produce the black outlines as seen in the final work. The fact that Siegelaub and Wendler created the material piece and Andre only provided the idea foregrounds the de-materialization of art, as the artist, a creator of art, is cited here as Andre. Second, like all following works, the use of an everyday office machine as a mode emphasizes its de-aestheticization. On the other hand, this work also contains the self-reflexivity typical of artist's books. During a later interview when asked why the squares began in the top left corner, Wendler said it just occurred to him that it was "like writing." [1]This subconscious decision demonstrates that the immaterial idea of art is still bound by its material medium, in this case, established conventions of the codex format. Further, the transformation of a three-dimensional object (the cube) into a two-dimensional figure on the page points to the limited transference of information through the codex format, whereas the progressive accumulation of squares as the audience flips through the pages points to the book's temporal affordances. Each page consists of a phrase, translated into English, German, and French, that offers varying explanations of the dots or lines on the page.

- Robert Barry

- Robert Barry (born 1936) is a New York based artist whose installations, non-material works, and performances highlight the multi-faceted nature of space in art[11] and the power of language to change the perception of said space.[3] Barry's 25 pages consist of repeating grids of dots, with the bottom of the final page also including the words "ONE MILLION DOTS." Again, this piece speaks to the temporal and linear nature experience of a codex. As the viewer flips through each page, he or she has a sense that there are many dots; however, only on the last page, the viewer understands that one, the dots on each page are meant to be viewed in relation to each other (accumulated), and two, there are a finite, specific number of dots. Through the strategic placement of language, Barry is manipulate the perception of past sensory experiences.

- Douglas Huebler

- Douglas Hubler (1924-1997) began his career as a painter before transitioning to sculptures, photographs, and multimedia work that often incorporated text. He is considered one of the founders of Conceptual Art, and, in his artist's statement for a show at Seth Siegelaub's gallery a year after the publication of the Xerox Book, famously declared, "The world is full of objects, more or less interesting; I do not wish to add any more."[12] Out of all the Xerox Book artists, Huebler's work may be considered the most de-materialized, and indeed, his 25 pages heavily engages the audience's rational intellect. The formulaic language is reminiscent of a mathematical text[7], and highlights the de-aestheticization and informational transmission of Conceptual Art[2] The format further enables this latter goal, as the codex had mostly been relegated solely as a tool for the communication of ideas in the contemporary consciousness. However, this codex's inherent nature as the physical manifestation of fine art, particularly those within the first edition, places value back on the codex as an object, raising the question of whether visual art can ever evade materialization.

- Joseph Kosuth

- Joseph Kosuth (born 1945) is another pioneer of the Conceptual Art movement. In 1969, he published a seminal essay titled, "Art After Philosophy," which explores the relationship between words, ideas, and visual images.[13] His belief in language-based art is evident in his 25 pages, that include a series of sentences describing a non-existent image of the project's creation process, such as "Photograph of ink and toner used." Similar to Huebler, Kosuth's "art" manifests in the audience's imagination[3] in typical Conceptual Art fashion and again references the notion of the book as an idea. Self-reflexivity is also prominent in this as it draws attention and "aesthetifies" the creation process of the material object at hand. According to Wendler, Kosuth had initially hoped to physically pass elements in the creation process (such as ink and toner) through the Xerox machine, but had been asked to reconsider due to its infeasibility.[1] Perhaps this points to limits in the documentary capabilities of the codex format and, more specifically, the photocopy technology; at the same time, the final product also highlights the power of printed words to generate ideas that can overcome such a barrier.

- Sol LeWitt

- Sol LeWitt (1928 - 2007] was a Conceptual and Minimalist artist, most famous for his large-scale wall drawings. He began his career as a graphic designer, an experience that influenced his reliance on lines and simple shapes in later works.[14]LeWitt emphasized the conception of his works over the material through a refined artistic process: first, he decided on a system of elements; then, he mapped out various permutations through a combination of the elements; last, he would entrust this "blueprint" to others for production. LeWitt's work in the Xerox Book reflects his process, with each of the first 24 pages depicting some rotation of squares filled with horizontal, vertical, and diagonal lines, and the last 25 page revealing the overall schematic. Interestingly, LeWitt's work is the only one to reference an outside piece of art, as they served as the "blueprint" for his first wall drawings in 1969. Though LeWitt may seem to have violated Siegelaub's stipulation that works in the "Xerox Book" must be the art, the notion in Conceptual Art that the idea takes precedence over its physical manifestation allows LeWitt's "blueprint" to take greater importance. The codex format, with its element of "copies," underscores the idea behind the work and its two physical iterations as the same.

- Robert Morris

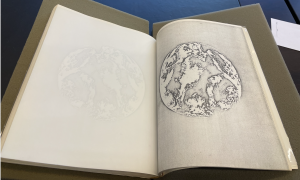

- Robert Morris(1931 - 2018) was an American artist and art critic whose work touched upon several art movement during his lifetime, from Minimalist to Conceptual Art. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, bracketing the publication of the Xerox Book, Morris experimented with unorthodox material, such as dirt or masses of thread, to create "Anti-form" pieces that lacked rigid structure. His 25 pages also demonstrate a similar idea, featuring an imperfect copy of the photograph of Earth as taken from space.[3] Though the audience recognizes the picture is of Earth, imperfections from the Xerox machine are evident: the circular planet and the clouds lacks a definitive outline; there are glitches and toner dust marks surrounding the image; each of the 25 pages vary in their quality. Morris's work most plainly comments on the unreliability of the Xerox machine and perhaps even physical prints as a whole.[7] However again, his use of the technology to create fine art adds complexity to any potential critique.

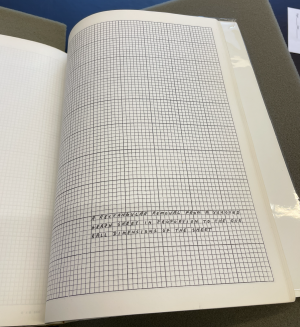

- Lawrence Weiner

- Lawrence Weiner (1942 - 2021), the final artist in the Xerox Book, was another key figure in the Conceptual Art Movement. He is famous for his "Declaration of Intent," formulated in 1968:

- 1.The artist may construct the piece.

- 2. The piece may be fabricated.

- 3. The piece need not be built.

- Each being equal and consistent with the intent of the artist the decision as to condition rests with the receiver upon the occasion of receivership.[3]

- This last line emphasizes his belief in audience engagement with the work, which is also evident in his contributions to the Xerox Book. Each page consists of a xeroxed graph-paper with the following text:

- A RECTANGULAR REMOVAL FROM A XEROXED GRAPH SHEET IN PROPORTION TO THE OVERALL DIMENSIONS OF THE SHEET

- Wendler recalls that Weiner had intended these words as instructions for the audience to alter something about the work (remove it) in order to manifest the intended art.[1] These instructions to destroy highlights the another dimension of the paperback codex format at this time, its fungibility. Furthermore, the instructions de-emphasize its value as an object, in accordance with Siegelaub's intentions. However, the first-edition copy at the Kislak Center (and most likely all other copies) retains its pages, which again points to the limitations of art to evade all commodification.

Reception and Legacy

Upon its publication, the Xerox Book was considered a groundbreaking success. Like its conceptual predecessors, it subverted traditional notions of both making and exhibiting art and further demonstrated the affordances of the codex format to disseminate the beliefs of its artists. The book, according to an art critic, Chris Rawcliffe, has since become one of the "most iconic and collectable items to come out of the Conceptual Art scene of the sixties and seventies."[7] However, its popularity as a collectable item also relate to criticism pertaining the book. Though the codex format, specifically its resemblance to a cheap mass-marketed paperback, ought to have aided Siegelaub's goals to de-aesthetify and shift attention away from the physical object, it still took on high monetary value. Kislak Center bought its copy for $450, and other copies, as of May 2022, are sold on second-hand markets, like AbeBooks for 400 to 4000 USD.This reality might point to an impossibility for any aspect of American society in escaping the current capitalist system; or perhaps, answers might be found in the history of the book. Before mass printing could churn out seemingly infinite copies of books, books were of limited quantity, which made a single book a valuable object. Similarly, Siegelaub and Wendler only produced one edition with 1000 copies; its scarcity, along with its nature as fine art and the respectable position of its contributors, would make these books valuable. On the other hand, perhaps this decision was part of Siegelaub's comment on art and society. Other criticism include the fact that the Xerox Book was not in fact xeroxed, rumors of pages being upside-down in certain copies, and that original works in the publication had found their way into private art collections. Regardless, as Rawcliffe believes, such antagonism only compounded the impact of the Xerox Book on the art world.[7]

The Xerox Book has directly inspired later works. Some include the 2010 Rollo Press Xerox Book, which is part of the Bootleg Series at East Side Projects and Pau Wah Publications Xerox Book (NYC), which asked street photographers to explore New York City. Its pioneering use of Xerox as an artistic mode also lay the foundation for the collages of Jean-Michel Basquiat, who viewed the Xerox as so integral to his work that he purchase a machine for his studio.[15]

Evidently, the Xerox Book was and remains a seminal work at the intersection of art, books, and print technology.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 "Jack Wendler speaks about the XEROX BOOK." YouTube, uploaded by KADIST, 25 June 2013, www.youtube.com/watch?v=85wsUOaqCN8. Accessed 5 Apr. 2022.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Berryman, Jim. "Art as document: on conceptual art and documentation." Journal of Documentation, vol. 74, no. 6, 13 Aug. 2018, pp. 1149-61.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Gilman, Amy. Organizing Art: Information Theory and Conceptual Art. 2005. Department of Art History and Art, Case Western Reserve U, PhD dissertation.

- ↑ Cie, Chistina. Ink Jet Textile Printing. Woodhead Publishing Series in Textiles, 2015.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Owen, David. Copies in Seconds: How a Lone Inventor and an Unknown Company Created the Biggest Communication Breakthrough since Gutenberg: Chester Carlson and the Birth of the Xerox Machine. New York City, Simon & Schuster, 2004.

- ↑ Mehta, Stephanie. “Xerox nostalgia” CNN. 22 Jan 2010. https://money.cnn.com/galleries/2010/technology/1001/gallery.xerox_copiers.fortune/index.html Accessed 5 Apr. 2022

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Rawcliffe, Chris. "The Xerox Book: the book that was an exhibition that became an artwork." Ambit, vol. 214, fall 2013, pp. 80-86.

- ↑ Ismail-Epps, Samantha. “Artists’ Pages: A site for the Repetition and Extension of Conceptual Art.” Visual Resources, vol. 32, 2016, pp. 247-262

- ↑ “The Xerox Book (Carl Andre, Robert Barry, Joseph Kosuth, Sol LeWitt, Robert Morris, Lawrence Weiner).” Ivory Press. 2022. https://www.ivorypress.com/en/libreria/shop/siegelaub-the-xerox-book-2/. Accessed 4 May 2022.

- ↑ “Carl Andre.” Tate. 2022. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/carl-andre-648. Accessed 4 May 2022.

- ↑ “Robert Barry.” QG Gallery. 2022. https://qg-gallery.com/robert-barry/. Accessed 4 May 2022.

- ↑ Miller, John. “Double or Nothing: The Art of Douglas Huebler.” Artforum (Online Access). April 2006. https://www.artforum.com/print/200604/double-or-nothing-the-art-of-douglas-huebler-10617. Accessed 4 May 2022.

- ↑ “Joseph Kosuth – Shifting Art from “How” to “Why”.” Artland. 2022. https://magazine.artland.com/joseph-kosuth-shifting-art-from-how-to-why/. Accessed 4 May 2022.

- ↑ “Sol LeWitt.” The Art Story. 2022. https://www.theartstory.org/artist/lewitt-sol/. Accessed 4 May 2022.

- ↑ Kinsella, Eileen. “Basquiat Loved Photocopies So Much He Bought His Own Xerox Machine. Now the Artworks He Made With It Are Worth Millions.” Artnet News. 12 Mar 2019. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/basquiat-xerox-show-at-nahmad-hed-tk-tk-tk-1486210. Accessed 4 May 2022.