The Provincial Freeman and Weekly Advertiser

Overview

The Provincial Freeman and weekly advertiser is a collection of weekly newspapers from 1854-1857 published by Mary Ann Shadd Clad. The newspapers were written by different Black people, published in Canada, and preach freedom and equality for Black people in North America. The largest collection of the newspapers belong to the University of Pennsylvania.

How They Got to The University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania has the most issues of The Provincial Freeman and weekly advertiser. There are not many owners of the original copies of the newspaper, which were normally two pages, front and back, with seven columns per page. The collection of newspapers was gathered by Mr. William Still. He most likely received his copies of the newspapers via the mail, as he lived in Philadelphia. His collection was given to the University of Pennsylvania in 1914 by F.E. Still, one of William Still’s relatives.[1]

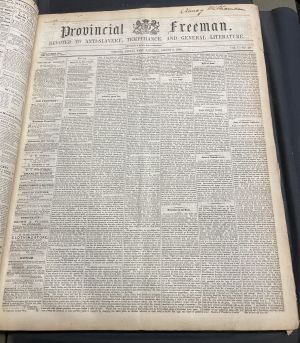

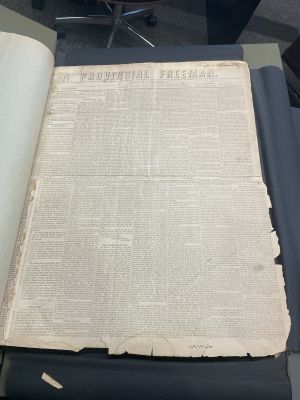

The Pages of the Newspapers

The newspapers are made out of super large, flimsy, and fragile paper so it would have been hard to preserve the newspapers over a long period of time. This explains why the newspapers are not in great condition. Between being shipped to the United States from Canada and being printed close to two centuries ago, it is clear why many of the pages are ripped and worn down. Newspapers in the 19th century were commonly printed very large because it was less expensive to print larger pages that could also include many advertisements. Every page in the newspaper is filled with advertisements, which helped fund the newspapers for around three years. Also, subscribers paid “one dollar and a half” in advance to receive the newspaper, which also helped fund it.

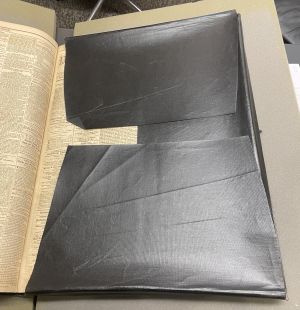

After They Got to the University of Pennsylvania

After the newspaper's arrival at Penn, they were rebound into a book sometime during the 20th century. Rebounding the newspapers into a book makes it much easier to keep the newspaper together and in good condition. The cover of the book is constructed of black Buckram cloth and is roughly 22 x 16.5 inches, making the book very heavy. While the back cover has huge black flaps that are used to maintain and cover the edges of the book.

William Still

Mr. William Still, a Black abolitionist who lived in Philadelphia, was a sporadic contributor to the newspaper and was responsible for distributing the newspapers to subscribers in Philadelphia.[1] It seems that Still was an avid reader of the newspapers because his copies are extremely worn down, as the pages have a yellowish tint with stains throughout. Also, there are sections of pages that have been cut out, which was probably because Still found these sections significant and necessary to keep, possibly in a scrapbook.

Background

Although William Still was never an enslaved person himself, he comes from a family where both of his parents were enslaved. However, both of his were able to escape slavery, as his father bought his freedom and his mother successfully escaped from slavery on her second attempt.[2] His parents fled to New Jersey and purchased a farm, where William Still was born in 1821. He worked on the farm as a child and barely received formal education but was able to somewhat educate himself through a lot of reading.[2] When he was twenty, he left home and a few years later went to Philadelphia, where he began to work as a clerk for the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. During his time working for the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, he provided consistent assistance to the Underground Railroad in Philadelphia.[3] He left a lasting legacy on the Underground Railroad for years to come. Also, Still was named the head of a vigilante committee in 1852 with other prominent abolitionists of the time whose purpose was to help fugitives who came to Philadelphia. He was responsible for leading, organizing the group and making sure they had the funds to assist every fugitive while keeping records. Between 1852 and 1857, the committee helped around 495 fugitives with things like financial aid, clothing, and train tickets to Canada.[2]

Underground Railroad

William Still is most famous today for his contributions to the Underground Railroad in Philadelphia. Specifically, it is known that about 95% of enslaved people that used Philadelphia to gain freedom stayed at Still’s home, which was renowned for being a safe space for enslaved people.[2] Still was most involved in the fight against slavery from 1855-1859, during the lifespan of The Provincial freeman and weekly advertiser, and during this time he played a critical role in freeing almost 60 enslaved each month.[2] He published a famous book, The Underground Railroad Records, that focuses mainly on the enslaved people themselves and their struggles and bravery as fugitives.[3]

An interesting story about Still while he was helping with the Underground Railroad is that he unknowingly helped his brother who was a fugitive. His brother was left behind in slavery, as their mother fled for freedom fourty years prior. After arriving North, Still’s brother contacted William for help, which is when they put the pieces together that they were brothers.[2]

Mary Ann Shadd Cary

After publishing the Provincial Freeman and weekly advertiser, Mary Ann Shadd Cary became the first female publisher in Canada and first Black female publisher in North America. She was an advocate for American enslaved people to emigrate to Canada, where they could gain freedom. Also, she is now known for being the most famous Black female writer of her generation.[4]

Shadd grew up in an elite household in a free northern Black community and was the oldest of thirteen children. Because her family had money she was able to get a formal education, which was not very common for women at the time. Her family was involved in the abolition movement so she was connected with prominent abolitionists, which, combined with her education, gave Shadd the foundation to begin her activism.[4] She started her career as a teacher before becoming a prominent abolitionist. Her work in all-Black schools further drove her passion for activism, as she saw up close the disadvantages Black children had.[5] She was driven to make a change and she was very stubborn with her views, as she was very judgemental of activists who did not share her ideas. She thought that free Blacks needed to turn their full attention to anti-slavery reform, rather than living similar lifestyles to middle-class White people.[4]

Shadd was a controversial figure at the time because of her unconventional beliefs and ideas. Not only was she an activist for Black people in North America, but she also was a major activist for women’s rights. She was known to be an early Black nationalist who did not follow the masculinist ideals of the time.[5] Shadd had no issue with ignoring the gender hierarchy of the time and was willing to publicly denounce distinguished male figures.[4]

Historical Significance

The Provincial Freeman and weekly advertiser was one of two major newspapers for enslaved people that escaped the United States and fled to Canada before the Civil War in the United States.[1] The newspapers included news about the racist nature of the United States, so the former enslaved people could stay up to date with their past lives. It was also a way to get news to abolitionists in different regions, like William Still. The purpose of the newspapers was to inform the large group of free Black people, who were usually affluent and highly educated, about the racial landscape. Also, the newspapers gave the Black people in the United States a perspective on what it was like to live in Canada, so they could make the decision if they wanted to flee there.[1] It was important to give the American Black people this perspective because it gave them hope for a better future, as Canada was a place that they could succeed without as much racial discrimination. Ultimately, the Freeman was a way to make it known to the public of the advancements and progress of Black people in Canada.[1]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Murray, Alexander L. “The Provincial Freeman: A New Source for the History of the Negro in Canada and the United States.” The Journal of Negro History, vol. 44, no. 2, 1959, pp. 123–35, https://doi.org/10.2307/2716034.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Gara, Larry. “WILLIAM STILL AND THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD.” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies, vol. 28, no. 1, 1961, pp. 33–44, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27770004.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Mitchell, Frances Waters. “WILLIAM STILL.” Negro History Bulletin, vol. 5, no. 3, 1941, pp. 50–51, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44246634.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Yee, Shirley J. “Finding a Place: Mary Ann Shadd Cary and the Dilemmas of Black Migration to Canada, 1850-1870.” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, vol. 18, no. 3, 1997, pp. 1–16, https://doi.org/10.2307/3347171.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Rhodes, Jane. Mary Ann Shadd Cary: The Black Press and Protest in the Nineteenth Century. Indiana University Press, 1999.