The Nuremberg Chronicle

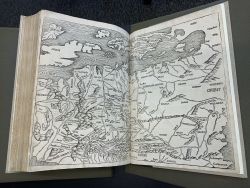

The Nuremberg Chronicle is a historical text structured around the 7 stages of the world, narrated from a biblical point of view. The 7 stages are the following: from creation to the Deluge, up to the birth of Abraham, up to King David, up to the Babylonian captivity, up to the birth of Jesus Christ, up to the present time (1493) and finally the outlook on the end of the world and the Last Judgment. It was first published in Latin on July 12, 1493, in the City of Nuremberg, Germany by Anton Koberger. Its original name is the Liber Chronicarum and it was written and designed by Hartmann Schedel.

Introduction/Historical Background

Its original name is the Liber Chronicarum (Book of Chronicles) and it was written and designed by Hartmann Schedel. It was first published in Latin on July 12, 1493, in the City of Nuremberg, Germany. Two Nuremberg merchants, Sebald Schreyer and Sebastian Kammermeister, enlisted the Latin version of the chronicle. They also commissioned Georg Alt, a scribe at the Nuremberg treasury, to translate the work into German. [1]Both Latin and German editions were printed by Anton Koberger, a socialite with the financial means to carry a project this big [2] Koberger ran the most productive and large-scale publishing production during that time – which allowed him to carry out full-volume and expensive projects.

Hartmann Schedel

The author of the Nuremberg Chronicle is Hartmann Schedel, a German humanist physician, historian, and one of the first cartographers to use the printing press. He was born in Nuremberg. He also enjoyed collecting books as well as writing them, specifically art and old master prints. [3]

Material Analysis of the Chronicle

This copy of the 1493 codex of Hartmann Schedel's ‘‘Nuremberg Chronicle’’is from the Rare Book Collection Folio of the Kislak Center for Special Collections at the University of Pennsylvania. It is an original copy.

External Structure

Binding and Case

This copy of the Nuremberg Chronicle is rebound. It has a modern rebind, so this copy of the book is bound in modern one quarter full brown calf over linen; six raised bands on spine; one maroon morocco label on a panel with title and imprint date in gold; edges gilt. Housed in a linen case.

Internal Contents

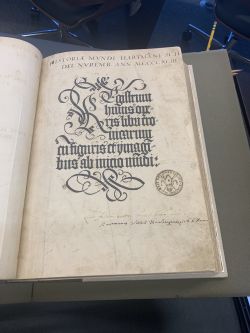

Title Page

There is a blank leaf preceding the title leaf with Latin ms. inscription and shelf-mark, recording the purchase of the book from bookseller Ludovicus Niolus by Giacomo Sartori (approximately added in 1650s) so way before Charles Burr.

Previous Ownership/Signatures

This copy was bought from Charles Burr in 1937 by the Penn Libraries. From examining this copy and other substrates he owned, we know that Burr did not mark his books. Signs from previous ownership are the following. On the second page, there is a rewrite of the already printed title in the middle of the page, in black in at the top. It also has a round armorial stamp of the library of San Giacomo Maggiore, Bologna, Italy, on title leaf, also inscriptions/signatures of people at the bottom of people who owned it before Charles Burr. There is brown ink throughout the book which sometimes acts as notes on the sides or in other cases, there is a rewrite of already printed text. We can see different people’s footprints in this book.

Blank Pages

Most copies of the Nuremberg Chronicle include blank pages between the 1493 present and the Last Judgment (last stage of the book). In “Rare-book Detective Work: The Nuremberg Chronicle” by Anne Peale, she describes how the blank pages serve as a medium for individual markings of the person reading the chronicle. It is more than just a “symbolic representation”, rather a form of self-expression and intimate bonding with the book. Hartmann Schedel did not think that the Second Coming was that far into the future, given that he only left about six pages for historical account from 1493 until the Last Judgment. [4]

Hand Coloring

There is one full hand colored page in the book. Some sports of light blue and brown wash, and red ink are in other leaves.

Marginalia

Examples of early Latin notes are in Leaf CCLXVII, a full leaf cut with early Latin ms. notes on margins, partially lost due to cropping. The woodcut on leaf XXVIIIv "Lacedemonia" also has some early ink drawings on it. Leaves XLIIIv and XLIIIIr, cut of "Venecie" contains hand coloring of light blue and brown wash. Leaves XCVIIv and XCVIIIr, cut of "Ratisbonas", and leaves XCVIIIv and XCIXr cut of "Viena-Pannonie" also have hand colored in light blue wash.

Impact/Significance

Taking into account the grand feat it was to print this manuscript, I came to the conclusion that the purpose of the book was not only to highlight world history, but to extol the grandeur and richness of their cherished Nuremberg. Though the information was quickly forgotten, it remained famous for its impressive graphic design, its printing, its woodcuts and descriptions of cities. [5] Because of the impressiveness of the large paintings and the techniques, the work was a commercial success, not only in Germany, but in Italy as well. The extensive use of these woodcut images in this text and their prominent location within the text block revolutionized book production in Europe. Many scholars argue that this text “established new technical standards regarding complexity of layout.” [6] It had historical significance for Germany given its influence by the Renaissance humanism originating in Italy in the 15th century, which aimed to portray Germany as important as classical Italy. That was the purpose of the book – to show Nuremberg’s wealth, compared to Italian states. [7]

Circulation of the chronicle

The book was originally published in Latin – so it wasn’t intended for the masses to read. The audience was mostly literate and cultured white men. After the German version was commissioned, the general public had the chance to appreciate this masterpiece to its full extent.

References

- ↑ [1]Penn Libraries.

- ↑ [2] Mosurinjohn and Ascough, The Nuremberg Chronicle: Art, Artifact, and the End of the World

- ↑ [3]Hartmann Schedel, Biography

- ↑ [4]Peale, Anne; Rare-book Detective Work: The Nuremberg Chronicle

- ↑ [5]Jeremy Norman's History of Information

- ↑ [6]Boydell & Brewer, 15th Century Studies

- ↑ [7] William Shire, The Nuremberg Chronicle: A History of the World