The Herculaneum Scrolls

A Brief History

The Herculaneum papyri—upwards of 1,800 largely-philosophical texts on scrolls dated to the 18th century—comprise what is now considered the “only library from the ancient world”[1]. This collection of papyrus scrolls originally hails from the Herculaneum Villa dei Papiri ("Villa of the Papyri"), an estate in the ancient Roman city on present-day Italy’s Bay of Naples. The Villa dei Papiri is famous for its contents' carbonization and consequent preservation resulting from the eruption of nearby Mount Vesuvius on August 24, A.D. 79. In the aftermath of a 10-mile cloud projection of ash and pumice into the stratosphere, the city of Herculaneum was buried under approximately 60 feet of ash, mud, and layers of volcanic material[2]. Due to Herculaneum’s more favorable proximity from winds on the coast and west of Mount Vesuvius, its artifacts were sheltered from the worst of the same 18-hour eruption that similarly ravaged Pompeii, Oplontis, and Stabiae[3]. The pyroclastic flows that blanketed the Herculaneum Villa dei Papiri consequently carbonized and preserved its contents for two millennia, while furtively concealing the majority from looters. In fact, when the first charred papyri were discovered in 1752, excavators first assumed they were either blackened tree logs or carbonized fishing nets[4].

Excavations and Present Locations

A number of archaeological excavations and consequent discoveries took place in Italy from 1752 to the 1990s, bringing the total presently-known collection to approximately 1,826 papyri[5]. In 2016, a group of scholars—headed by Robert Fowler, the professor of Greek at the University of Bristol—addressed an open letter to the Italian authorities warning that further excavations are crucial in a race against prospective findings’ deterioration[6].

Due to geographic dispersal through the transfer of scrolls or fragments as diplomatic gifts in the 1800s, the fragments are now located in Italy’s Biblioteca Nazionale di Napoli, the Institut de France, Oxford University’s Bodleian Libraries, and the British Library[7]. The scrolls’ political migrations prove a widespread recognition of the Herculaneum papyri as objects of cultural and material value—even when their charred text was indecipherable to early technologies.

Getty Villa, the Herculaneum Replica

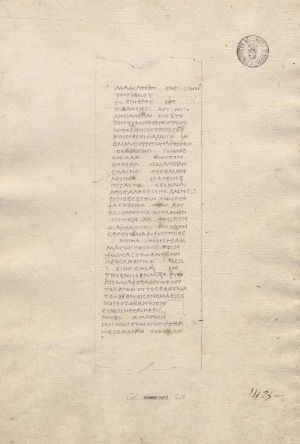

In the early 1970s, oil magnate J. Paul Getty—who had already owned a collection of Greco-Roman artifacts by this decade—commissioned a 360,000-square-foot, Malibu-based replica of the Villa dei Papiri presently known as the Getty Villa or Getty Museum. Architects involved in the project relied upon Swiss engineer Karl Weber’s plan (pictured) from the 18th century—the tunnels had been abandoned in 1764 and until modern excavations continued in the 1990s, the plan was the sole and ruling reference for the ancient villa’s format.

Buried by Vesuvius: Treasures from the Villa dei Papiri—what is considered the “first major exhibition on the Villa dei Papiri”—took place at Getty Museum from June 26 to October 28 of 2019 in collaboration with MANN, the Parco Archeologico di Ercolano (PA-Erco), and the Biblioteca Nazionale “Vittorio Emanuele” di Napoli (BNN). A detailed exhibition inventory can be found here, listing photos and descriptions of each included artifact—including unopened carbonized scrolls, a fragment of the carbonized On Rhetoric by Philodemus of Gadara, facsimiles, and Antonio Piaggio’s 1756 papyrus unrolling machine.

A virtual exhibition titled “Getty Live: Vesuvius Exhibition Tour” has been made available online as of December 2019. It is led by Kenneth Lapatin, the Getty Museum’s curator of antiquities and author of both Guide to the Getty Villa (2018) and Buried by Vesuvius: The Villa dei Papiri at Herculaneum (2019). Getty Museum also highlights a number of digital resources online—including a translation of Weber’s detailed excavation plan circa 1754-1758, which recounts descriptions, locations, and discovery dates for all rooms and artifacts.

Evolution of Softwares and Methods for "Unwrapping"

Post-carbonization, most of the Herculaneum papyri became so fragile that they approached destruction with every handling. This has posed a historical debate on the importance of continued preservation versus the possibility of immediate results—and gave birth to a diverse number of attempts to unfurl the papyri’s mysteries. In the 1750s, Camillo Paderni attempted to slice scrolls into halves and remove papyri layers, creating legible facsimiles but destroying the scrolls. In 1756, Antonio Piaggio invented a machine that painstakingly unraveled a single scroll just one centimeter per hour over the course of months or years. In 1819, Humphry Davy used chlorine to partially unroll 23 scrolls with limited success. Piaggio’s method met relative but long-lasting success—it was practiced into the early 20th century using replicas of the original machine, yielding partial recovery of hundreds of scrolls since its conception.

Starting in the late 1990s, scientists have used advanced imaging technologies to unravel, enhance, and decipher the contents of the Herculaneum Scrolls without destruction. These methods are explored on our Digital Rendering of Ancient Books wiki page, and include the following to date: transcription by multispectral imaging (1999-2001), digital rendering using X-ray computed tomography and nuclear magnetic resonance (2009-2011), Virtual unrolling and deciphering of Herculaneum papyri by X-ray phase-contrast tomography (2016-2017), and Scanning and hyperspectral imaging with Diamond Light Source and a handheld 3-D Artec Space Spider (2019). A timeline of modern technologies and discoveries can be found on EduceLab’s website “From Damage to Discovery – A Timeline of Innovation”.

Databases and Catalogues

Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford offers public access to digital imaging of their collection of original papyri fragments, bestowed to Oxford University by the Prince of Wales in 1810.

The British Library offers public access to high-quality imaging of seven Herculaneum fragments deriving from a 1st-century BCE work written by the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus. The papyrus fragments entered the British Museum’s collection in 1906 upon Edward VII’s presentation.

On the CEDOPAL/MP3 database, University of Liège researchers state that they will soon feature the ability to search for “new categories of Greek and Latin papyri” including the Herculaneum papyri.

Chartes is an updated, digital Italian database for the Herculean Papyri first published by the International Center for the Study of Herculaneum Papyri in 2005 under the ISBN 9788890764400. Searches can be conducted under numerous categories, including by papyri or images. The comprehensive database includes high-definition imaging, as well as author, artifact state, unwinder identification, bibliography, and dimensions of fragments.

The Duke Collaboratory for Classics Computing & the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World’s website “Papyri.info” provides a database and transcriptions of Herculaneum papyri from worldwide compilation. It offers in-text transcriptions of acquired papyri, separated by fragments and linked to respective engravings, sketchings, and publications for additional context. Retrieved from the Herculaneum Society resource list.

The German Würzburg Center for Epicurean Research displays preserved sketches of pre-experiment papyri fragments dating back to the possession of King George IV and commissioned chemist Humphry Davy in 1819. Images are supplied by the Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019 and available for public download.

The National Library of Naples’ digital library offers “facsimilar transcriptions,” or precisely-drawn digital reproductions, of a comprehensive index of numerically-identified Herculaneum papyri. Significantly, some of these copies immortalize portions of writing that have since deteriorated on the original artifacts. This project was originally curated by the Mediatheque of the National Library of Naples (2010-2012). Retrieved from the Herculaneum Society resource list.

The Oxford Facsimiles of the Herculaneum Papyri (“PHerc collection”) contains high-resolution and low-resolution imaging of a host of facsimiles, made available through Bodleian Libraries and searchable by numerous identifiers. Retrieved from the Herculaneum Society resource list.

The Thesaurus Herculanensium Voluminum is a full-text German database of Herculaneum papyri spearheaded by the Centro Internazionale per lo Studio dei Papiri Ercolanesi, the Chair for Classical Philology I at the University of Würzburg, Gianluca Del Mastros, and Holger Essler from 2008 to 2013. The website contains approximately 149 recorded, searchable texts, and 268 inventory numbers. Its papyri are organized by author and link to the following source. Retrieved from the Herculaneum Society resource list.

Trismegistos’ Leuven Database of Ancient Books offers comprehensive information on relevant Herculaneum papyri—including provenance, timestamp, related publications, collections, script, authors, and genre.

The Würzburg Center for Epicurean Research offers digitized representations of their engravings published in Herculanensium Voluminum Quae Supersunt (Collectio Prior) and Herculanensium Voluminum Quae Supersunt Collectio Altera. Retrieved from the Herculaneum Society resource list.

Keep in Touch

If you are interested in developing discoveries, digital innovations, and updates regarding the Herculaneum Scrolls, consider visiting the University of Kentucky's EDUCELab news page.

- ↑ “Reading the Herculaneum Papyri: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow.” YouTube, Getty Museum, 25 Nov. 2019, www.youtube.com/watch?v=g-7-Xg75CCI. 8:10.

- ↑ “Mount Vesuvius Erupts.” History, A&E Television Networks, 24 Nov. 2009, www.history.com/this-day-in-history/vesuvius-erupts.

- ↑ “Mount Vesuvius Erupts.” History, A&E Television Networks, 24 Nov. 2009, www.history.com/this-day-in-history/vesuvius-erupts.

- ↑ “Buried by Vesuvius: Treasures from the Villa Dei Papiri.” Getty, Getty Museum, www.getty.edu/art/exhibitions/villa_papiri/inner.html.

- ↑ "IV: The Herculaneum Papyri," Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies, Volume 33, Issue Supplement_54, February 1986, Pages 36–45, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-5370.1986.tb01374.x

- ↑ O'Hare, Ryan. “Academics Urge Italian Authorities to Excavate a Library Buried by Vesuvius.” Daily Mail Online, Associated Newspapers, 30 Mar. 2016, www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-3515386/Like-digging-20-new-Shakespeare-plays-Academics-urge-Italian-authorities-excavate-library-buried-Vesuvius-believe-packed-priceless-historic-texts.html.

- ↑ “2,000-Year-Old Herculaneum Scrolls from Institut De France Being Studied Using UK's Synchrotron, Diamond Light Source.” Diamond Light Source, UK Research & Innovation (UKRI) and Wellcome Trust, 2019, www.diamond.ac.uk/Home/News/LatestNews/2019/03-10-2019.html.