The Handmade Papers of Japan

Introduction

"The Handmade Papers of Japan" stands as a testament to the dedication and artistry of Japanese papermakers, brought to life through the collaborative efforts of almost a dozen contributors. Compiled mainly by Thomas and Harriet Tindale, this remarkable collection, consisting of 4 volumes, was published in a limited edition of no more than 250 copies by Charles E. Tuttle Publishing in 1952 aiming to document ancient papermaking processes and archive surviving artifacts [1]. Within its pages, The Watermark Collection, not only showcases a breathtaking array of handmade Japanese papers but also gives insight on the elusive process of Japanese watermarking and encapsulates the spirit and essence of their creators. Moreover, the collection as a whole pays homage to the enduring legacy of these skilled artisans who have painstakingly preserved the traditional techniques and timeless beauty of Japanese papermaking across generations. It serves as an enduring testament to their unwavering craftsmanship and commitment, ensuring that their invaluable contributions are solidified within the annals of history.

A Collaboration of the East and the West

The ending of World War II, in September of 1945, marked a significant turning point in Japanese art[2]. After the war, Japan underwent a major reconstruction effort with significant involvement from the United States, leading to a remarkable economic boom. This rebuilding process revitalized city centres and created opportunities for cultural institutions to flourish. Artists began to reject traditional techniques and styles, opening up new possibilities for artistic expression, especially through avant-garde movements. Amidst this bustling environment of rebirth and revitalization, the profound cultural legacy of Japan loomed large. It served as a powerful source of inspiration, fueling a renewed appreciation for the country's artistic heritage and traditions. Since Japan was largely isolated from the West, pre-war, the newfound American involvement in Japanese government and society, elicited intense curiosity from visitors who sought to understand and engage with the mystery of Japanese art and culture (source). This cultural exchange resulted in a rich tapestry of artistic collaboration between Japanese and American artists, further enriching the post-war artistic landscape.

Within this context, the publication of The Handmade Papers of Japan became possible due to a fortuitous combination of circumstances, one of them being the willingness of the remaining older Japanese papermakers and scholars[3]. The Japanese, keen to make peaceful connection with the West and appreciative of an esteemed American like Tindale acknowledging and celebrating their native artistry, went to great lengths to assist in making the book a tribute to the heritage of Japanese papermaking and educational resource for future generations (source-berger). As a result, the majority of people knowledgeable about the topic were drawn in and worked with the Americans to bring the project to fruition. To symbolize their collaborative effort, the tozai mon, or seal, found on many pages in the collection, consists of two characters: one for higashi, the East and one for nishi, the West (source-preface/ symbol picture).

Major Contributors

Thomas Keith Tindale

Born on August 3 1909 in South Hanover, Massachusetts, Thomas Keith Tindale’s captivation with bookmaking began in 1928 with his first job at Perry Elliot printing company in Lynn, MA [3]. Despite his fascination with the printing press operation, Tindale realized that he didn’t have a future in the business and decided to return to high school and eventually attend the University of Virginia. After three years in Virginia, Tindale ended up finishing his bachelor’s degree at Stanford and subsequently became a master’s fellow in Public administration at Syracuse University from 1933-34. He began working as an apprentice to Governor John G Winant of New Hampshire, as well as the Public Administration Clearing House in Chicago, the US Conference of Mayors, the American municipal association and the American Public Welfare Association in subsequent years[3]. Tindale continued his studies at the University of Chicago where he focused on the Principles of Administration and Higher education Administration (1945-46) and finally completed his Ph.D dissertation on Education and Training and the Japanese Public Service. Initially, Tindale aimed to gain the position of president or vice-president of a state university but admits that there was “hardly any certainty as to whether this ambition could be realized” (source). From 1946 to 1951 he became an advisor to the Japanese Civil Service, where he trained various groups of officials, staff and municipal authorities in administrative management[3]. His experience with the educated and ruling classes of Japan, gave Tindale the status to approach anyone he wished to meet serving as a stepping stone for connections with the scholars and historians of paper-making that would be invaluable to the creation of the collection. Additionally, his extensive travel through Japan sparked his love and appreciation for Japanese arts and crafts. Although the specific time when Tindale became enamoured with Japanese papermaking isn’t clear, he had begun writing to his wife about his fascination with Japanese wood block printer in 1947[3]. By 1949, he was already talking about writing a book, an idea that was seemingly solidified by his visit to the Efficiency Bureau, where he was shown some beautiful examples of watermarking[3] . Over the next 3 years, his visits to the Oji Paper Mill, and his collaborations with his wife, Harriet Tindale who edited the work, and his interactions with people like Mr. Seki, responsible for the creation of the majority of handmade artifacts in the collection, Thomas took every learning opportunity he had to truly become a master in the subject. The Tindales’ painstaking attention to detail and hard work produced a number limited edition of books that honored Japanese papermaking culture in its content but also in its structure and fabrication.

Charles E Tuttle Jr.

Charles Egbert Tuttle Jr. (1915-1993) was a prominent publisher and book dealer known for his contributions to Japanese literature [4]. Born in Rutland, Vermont, Tuttle studied history and literature at Harvard University before joining his family's publishing business. His interest in Japanese culture and literature grew during his time in the US Army, stationed in Japan after World War II. In 1948, Tuttle established the Charles E. Tuttle Company in Tokyo, becoming the 31st corporation approved by the occupation administration. The company began importing and distributing American and later UK paperbacks, newspapers, and magazines to the US forces. Tuttle expanded the company's publishing program in 1951, commissioning translations of renowned contemporary Japanese literature by authors such as Kawabata, Mishima, and Tanizaki. The company also published dictionaries, grammars, books on Japanese art, and the first popular books on Japanese martial arts. In the creation of the “Handmade Papers of Japan”, Tuttle’s company wasn’t the first choice for the publication for of the collection. However, the close alignment of Tuttle’s ideology with Tindale’s goals ultimately made their collaboration more favorable over other publishing companies [3]. Tuttle's influence in Japanese publishing extended beyond his own company. He founded the Tuttle-Mori Agency, which became Japan's largest literary agency. The agency represented notable UK authors and publishers, including Jeffrey Archer, Frederick Forsyth, and Brian Fremantle. Many professionals in the Japanese publishing industry trace their roots back to Tuttle's ventures. Recognized for his contributions to East-West understanding, Tuttle received the Order of the Sacred Treasure from Emperor Hirohito of Japan in 1983. In later years, he focused on the used and rare book business, dividing his time between Vermont, Hawaii, and Japan. His dedication to promoting Japanese literature and culture established a lasting legacy in the publishing world.

Material Analysis

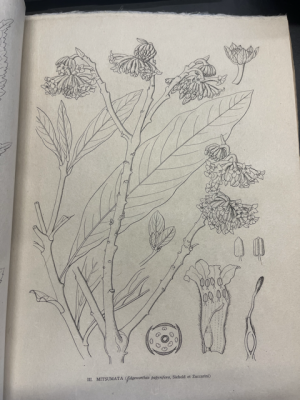

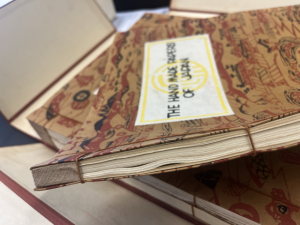

The Handmade Papers of Japan consists of 4 volumes: The Handmade Papers of Japan, The Seki Collection, The Contemporary Collection and The Watermark Collection. The stacked folio volumes are held in a shifu-covered portfolio which is kept closed by 2 ivory clasps. All of the paper in the books is made from mitsumata fibers, a commonly used material in Japanese papermaking. In terms of dimensions, the pages of the books can be classified as folio size. However, the collection deviates from the traditional codex binding. Rather than folding the sheets, the pages in these books are cut, stacked, and bound together for the most part. Interestingly, in Volume One, specifically in the section on paper-making, each sheet is folded with the crease facing outward, instead of being concealed within the spine, following the traditional way the Japanese would fold and bind paper.The first three volumes are bound by Kojiro Ikegami in a traditional Japanese style, using decorative paper and silk. The binding and end papers feature stenciled motifs depicting scenes of papermaking, paper objects, paper fiber plants, and early watermarks, paying homage to the realm of papermaking. What sets these books apart is that their spines are not closed as you would expect; instead, you can see the rough edges of the paper when looking at the spine.

The watermark collection is designed in a manner reminiscent of the larger box that houses the entire collection, albeit in a smaller size. It features the same type of ivory clasps to securely close the box. Upon opening, you'll find a foreword bound together in ribbon with a catalog detailing the contents. Additionally, there are 20 sheets of colored paper, each showcasing a unique watermark. Notably, the watermark papers are intentionally left unbound, allowing for easy access and convenient viewing of the individual pieces during exhibitions. The watermarked papers, themselves, are made from pure mitsumata fibers using the nagashizuki method and watermarked using the tesuri-kaki-ho or hand-rubbing method.

Japanese Papermaking

The two methods of paper formation, known as nagashizuki and tamezuki, hold significant importance as they serve as the foundation for both modern Oriental and Occidental handmade papermaking [5]. The term nagashizuki refers to the Japanese method, where the fibrous stock flows over the mould, while tamezuki represents the European and Occidental approach used in handmade paper fabrication.

In the nagashizuki method, the fibrous stock flows back and forth and from left to right across the mould, forming a sheet of the desired thickness. The surplus water is thrown over the "deckle" into the vat [5]. On the other hand, the tamezuki method involves drawing the stock on the mould, allowing the surplus water to drain through the mould with a slight shaking motion. In this method, the fibrous solution is retained within the boundaries of the "deckles," while the drainable part passes through the mould.

The nagashizuki method is ideal for producing tissues and thin mulberry bark papers, which the Japanese excel at. It was primarily used in Japan before the Meiji Era [6]. However, with the introduction of Western papermaking techniques, the tamezuki method was adopted to some extent for certain types of heavier papers[6]. Nevertheless, the nagashizuki method remains the best-suited approach for creating exceptionally thin, delicate, yet strong papers that the Japanese are renowned for. It offers several advantages, including the use of vegetable nori or tororo, which acts as an adhesive and creates an emulsion-like state. The nori helps distribute and suspend the fibers in the solution, preventing entanglement and knotting. It also slows down the drainage through the mould, allowing the fibrous pulp to remain on the mould for a longer time without solidifying. Without nori, the pulp would harden more quickly, resulting in faster drainage through the mould [1].

The nagashizuki system allows for the successful manufacture of exceptionally thin papers, but it is not limited to thin papers alone. Using this method, papers of various thicknesses can be built up [5]. The backward-forward, left-right motion on the mould. This motion prevents the adherence of foreign matter and helps distribute the fibers evenly on the mould's surface. The resulting paper is strong, with fibers lying in every direction due to the layers of pulp built up on the mould.

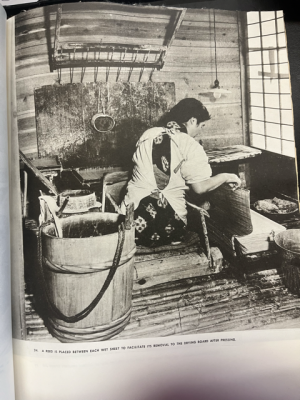

Next, the tosui process involves discharging the surplus fibrous solution over the deckle into the vat. As the watery mass is moved on the mould, the fibers adhere while impurities float on the surface and are eliminated over the edges of the mould [1]. This process removes both the surplus solution and impurities. After each dipping of the mould, the surplus material is allowed to flow over the deckles, resulting in the formation of a new sheet of paper.

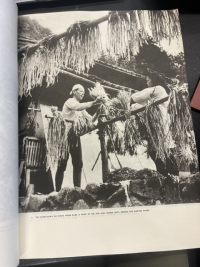

Overall, each step in the nagashizuki process contributes to the unique qualities of Japanese Paper that can only be achieved through many hours of physical labor and a deep understanding of each step in the process. The papermaker’s stance, movement and even posture can affect the efficiency at which they work but also the quality of their products [1]. However, due to its difficulty the craft is dying out; therefore, its detailed documentation in the collection serves to preserve the knowledge of previous generation for future ones, even if it’s only on paper.

Japanese Watermarks

History

Watermarking on Japanese handmade papers is believed to have started in the early 18th century, influenced by the use of reed or bamboo screens. Initially, watermarking was employed in art papers for their aesthetic appeals, such as mon shoin or sliding door papers decorated with family crests and elaborate designs. It was also used in hansatsu, feudal lords' banknotes, as a safeguard against counterfeiting. Craftsmen involved in producing hansatsu papers were subject to strict security measures, working in secluded compounds under constant surveillance [3]. Secrecy was maintained, with workers often taking oaths of secrecy and signing with their own blood. Little literature exists about hansatsu papers due to their secretive nature. The nagashi-zuki process was used to make these papers, and the technique was developed independently in different regions.

In 1871, the National Government took over the issuance of paper money, establishing the Shiheirvo or Bank Note Office. In 1876, the Shoshikyoku or Paper Manufacturing Office was created at Oji in Tokyo [1]. Its purpose was to produce unique papers that would be difficult to counterfeit and suitable for banknotes and financial documents. Today, it is known as the Oji Paper Mill of the Government Printing Agency. Watermarking played a crucial role in preventing counterfeiting, prompting extensive research by the new institution. Initially, watermarks were applied using the suki-keta-ho or Western wire screen method. In 1887, an Imperial Ordinance restricted the use of light and shade watermarks to the government and required prior notification for white watermarking.

In this collection

Every watermark in this collection was made using mitsumata fibers and the hand-rubbing technique to produce watermarks with different themes ranging from landscape and people, to birds, and to the watermarking process itself. Most importantly, a lot of the watermarks featured in this collection are from engraved plates that now have been lost. In the 1950s, the Oji Paper Mill, responsible for the the creation of some of the watermarks, was set on fire causing the loss of thousands of artifacts and pieces of history.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Tindale, T. Keith, Tindale, H. Ramsay, Hunter, D., Haar, F., Jugaku, B., & Seki, Y. (1952). The handmade papers of Japan. Rutland, Vt.: Charles E. Tuttle

- ↑ National Archives and Records Administration. (n.d.). Surrender of japan (1945). National Archives and Records Administration. https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/surrender-of-japan#:~:text=Yoshijiro%20Umezu.,the%20complete%20capitulation%20of%20Japan

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Berger, S. E., Tindale, H. Ramsey, Bixler, M., Bixler, W., Mardersteig, G., & Tindale, T. Keith. (2001). The handmade papers of Japan : a biographical sketch of its author and an account of the genesis and production of the book. Newtown, Pa.: Bird & Bull Press.

- ↑ (2019, December 23). From abacus to zen: A short history of Tuttle Publishing. Kyoto Journal. https://www.kyotojournal.org/culture-arts/from-abacus-to-zen-a-short-history-of-tuttle-publishing/

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Barrett, T. (2005). Japanese papermaking : traditions, tools, techniques. Warren, Conn.: Floating World .

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Hubbe, M., & Bowden, C. (2009). Handmade paper: A review of its history, craft, and science. Bioresources. https://repository.lib.ncsu.edu/bitstream/handle/1840.2/2282/BioRes_04_4_1736_Hubbe_Bowden_Handmade_Paper_Review_758.pdf