The Campden Wonder

Introduction

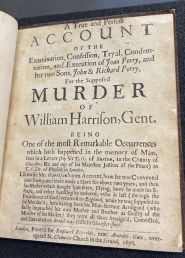

“A true and perfect account of the examination, confession, tryal, condemnation and execution of Joan Perry, and her two sons, John & Richard Perry, for the supposed murder of William Harrison, Gent. : being one of the most remarkable occurrences which hath happened in the memory of man / sent in a letter (by Sir T.O. of Burton, in the county of Glocester, Kt. and one of His Majesties justices of the peace) to T.S. Dr. of physick in London ; likewise Mr. Harrison's own account, how he was conveyed into Turkey, and there made a slave for above two years; and then his Master which bought him there, dying, how he made his escape, and what hardship he endured, who at last (through the Providence of God) returned to England, while he was supposed to be Murder'd; here having been his man-servant arraigned (who falsely impeached his own mother and brother as guilty of the murder of his master) and they were all three arraign'd, convicted, and executed on Broad-way Hills in Glocester-shier” is a 23-page pamphlet recounting the mystery of William Harrison’s disappearance, the subsequent trial and execution of the suspected Perry family, and William Harrison’s surprise return and time spent in Turkish servitude. The pamphlet is comprised of two main body sections, the first being a recounting of the case by Sir Thomas Overbury, the author of “A true and perfect account…” and the magistrate (also referred to as the Majesty’s Justice of Peace) of Chipping Campden. The second section is a letter from William Harrison to Sir Thomas Overbury describing his journey from being kidnapped and sold into slavery to eventually returning to Chipping Campden two years later. The pamphlet was first printed in 1676 in London, rebound in 1825, and currently resides in the University of Pennsylvania's Kislak Center for Special Collections - Rare Books Collection.

Historical Context and Provenance

Pamphlets and Their Historical Importance

While “A true and perfect account…” is labeled as a “Book” by the Franklin Library at the University of Pennsylvania, “Book” is not the most historically accurate term to describe “A true and perfect account…,” as several factors make the term pamphlet a more accurate descriptor. As stated earlier, “A true and perfect account…” was a sensational story of conspiracy, murder, and suspicious resurfacing, which fueled its popularity in Chipping Campden, the town of the event's occurrence, and throughout London. During the late 1600s, the public had an immense appetite for news, gossip, and true crime narratives,[1] pamphlets being the standard dissemination method for these sensational stories and prominent events. Because of pamphlets' inherent content and need to be timely, they were often shorter in length and smaller in size than traditional books. “A true and perfect account…” fits pamphlets ephemeral nature and size, coming in at a height of 19 cm and width of 13 cm.

Pamphlets at large played a critical role in spreading information, influencing public opinion, and shaping key societal debates in 17th-century England. Pamphlets were accessible, affordable, and “easier” to understand, making them attainable to a broader array of people and democratizing information, allowing people who might have previously not engaged in contemporary debates and discussions to do so. This was augmented by the fact that the 17th century was one of the most tumultuous in England's history (Source), with religious conflict and political upheavals plaguing the country. Pamphlets flourished because of this, allowing different groups to discuss their viewpoints, rally support, and criticize opponents. Two of the most well-known pamphlets come from this period, “Areopagitica” by John Milton (1644), a defense of freedom of speech and expressions, and “The Shortest-Way with the dissenters” by Daniel Defoe (1702), a satirical pamphlet mocking the Church of England.

Overarchingly, 17th-century pamphlets fall between a broadside and a book in format and were distinguishable primarily because of their detailed but timely nature. As time passed, other forms of media took over the role pamphlets traditionally played, and with the advent of digital media, pamphlets have been compressed into flyers, leaflets, and PDFs.

Genre Historical Context

When analyzing “A true and perfect account…,” it’s essential to look at the genres the pamphlet fits into and how the European public consumed them during the 17th century. “A true and perfect account…” can be thought of through three genre lenses: a “true crime” lens, a “legal case” lens, and a “sensational news” lens. Regarding “true crime,” the 1600s saw a growing enthusiasm for true crime-related cases, fueled primarily by the rise of the printed press, making these stories easier to disseminate and reach a wider audience. These accounts also speak to the public's growing curiosity with the darker elements of human nature and societal justice.[2] Concerning “legal cases,” this genre also saw a large uptick thanks to the printing press making legal knowledge broadly accessible,[3] but also due to the public's growing desire to be aware of their legal rights. What’s more, these cases often highlighted flaws within the legal system and posed complex questions that made one question the very basis of the system. The last genre characterizing “A true and perfect account…” is sensational literature, a genre that thrived in the 17th century thanks to the public's appetite for drama and the extraordinary. These works often exaggerated the most sensational aspects of real events, and in the case of “A true and perfect account…,” foregrounded the mysterious and astounding nature of the case while glossing over things that make the story less sensational but are nonetheless significant (i.e., social pressures the Perry family was facing as well as other inhabitants of Chipping Campden).

Many pamphlets were released during the 1600s in England that fall into these three genres and are akin to “A true and perfect account…,” not only in their sensational nature but in formatting as well. A comparable pamphlet is “Reflections upon the murder of S. Edmund-Bury Godfrey the design of Thompson, Farwell, and Paine to sham off that murder from the papists : the late endeavours to prove Stafford a martyr and no traitor, and the particular kindnesses of the Observator, and Heraclitus to the whole design, in a dialogue ; with a dedication from Mrs. Cellier,”[4] a 32-page long pamphlet discussing the mysterious circumstances around Sir Edmund Berry Godfey’s death, which many believed to be a murder-scheme executed by Catholics to prevent him from further investigating into the Popish Plot––a 1678 conspiracy theory that claimed that the Catholics were plotting to assassinate King Charles II. This pamphlet became widespread throughout England and added more fuel to the anti-Catholic sentiment of the time. Beyond the fact that both “Reflections upon the murder…” and “A true and perfect account…” involve alleged murder and what many believe to be false convictions, both speak to the larger concept of how society treated and consumed information and serve as a reflection of the justice system during 1600s Europe, a system easily swayed by public sentiment (pamphlets playing a large role in this) and political agendas rather than by true justice.

Rowland Reynolds

Rowland Reynold[5] was not only the seller of “A true and perfect account…”, but likewise responsible for the printing and publishing of the book. This was a common practice for individuals in the 17th century, especially those who focused on printing short-form texts/pamphlets like Reynolds. Given that pamphlets were mostly timely responses to current events, production needed to be extremely swift, meaning the roles of printer, publisher, and bookseller were often combined to streamline the process and get it to a large audience as quickly as possible. This is precisely the case when it comes to Reynolds, who operated out of “The Sun and Bible in the Poultry” for the latter part of the 17th century, acting simultaneously as a print and bookshop.[5] His shop was located “in the Poultry,” a street in the center of the City of London, meaning it was well-oriented for quickly distributing printed materials to the masses, especially pamphlets which were often sold in the streets.[6]

Regarding “A true and perfect account…,” the printing location is listed as “next Arundel-Gate, over-against St. Clements Church in the Strand,” referring to a location on the Strand, near the entrance of Arundel House directly across from St. Clements Danes Church. There are a few possible reasons for this differing address when comparing it to Reynold’s other works, which list “The Sun and Bible in the Poultry” as the printing location. It’s feasible that Reynolds operated multiple printing locations to reach a broader audience, as the demand for printed materials grew substantially during the late 1600s. Reynolds also could have formed a network of fellow printers to collaborate with and partnered with a particular one located “next [to] Arundel-Gate, over-against St. Clements Church in the Strand” to maximize reach and sales, especially for sensational publications like “A true and perfect account…” On the other hand, Reynolds could have also been using the address as a marketing strategy to attract a different clientele from a different region, as “next [to] Arundel-Gate, over-against St. Clements Church in the Strand” could be seen as a calculated reference to two prestigious locations in the City of Westminster, London. Concerning Reynold's other works, he primarily printed pamphlets, ranging from murder trials to political tracts, to sermons and theological discussions.[7]

It’s also important to take into account the context of what was happening at the time Reynolds printed “A true and perfect account…” in 1676. Just about a decade and a half prior to Reynolds printing “A true and perfect account…,” England had finally gained back its monarchy after 11 years of Republican rule under Oliver Cromwell, the period after referred to as the “Restoration Period.” The Restoration did lead to the reinstatement of the monarchy’s control over printing and publishing through the Licensing Act of 1662, which mainly focused on preventing the spread of dissent and had a profound impact on the printing industry, leading to restrictions on who could print, censorship and control over what could be printed, and growth of an underground market for unlicensed pamphlets, satisfying the public's demand for sensation and controversial content.

Contents

Case Overview

This case presented in “A true and perfect account…,” often referred to as “The Campden Mystery” or “The Campden Wonder,” centers around the supposed death of William Harrison, and his subsequent return. While “A true and perfect account…” does not go into detail about the backgrounds of its subjects and previous occurrences, for context, William Harrison was a seventy-year-old estate manager for a Viscountess and lived with his son Edward and his wife Mrs. Harrison, at the Viscountess’s estate in Chipping Campden.

One year prior to William Harrison's disappearance in 1660, two strange occurrences happened at the Harrison’s quarters, the first being the family getting robbed while away at church and the second being Harrison finding his servant, John Perry, screaming on the floor in complete hysteria, claiming he had been attacked by two men with swords, yet not a single cut was found on him.[8]

“A true and perfect account…”’s main text begins one year later, on August 16th, 1660, when William Harrison left his residence to go on foot to Charrington, a village only two miles away, to collect rent from the Viscountess’s tenants. As night came around, Mrs. Harrison sent John Perry to meet his master (William Harrison) halfway on his way back to Chipping Campden. But, as morning came, both Harrison and John Perry had still not returned. So, Mrs. Harrison sent her son, Edward, out to find the two, only for him to stumble upon John Perry alone, who then joined in on the search for Harrison. The two talked to one of the tenants whom Harrison was supposed to meet with the night before, who told them Harrison had, in fact, been there the night before, but knew nothing else. On their way back to Chipping Campden, they found a hat, band, and comb, all belonging to Harrison, the band having remnants of blood. The first person Sir. Thomas Overbury, the magistrate most likely in charge of this case and author of “A true and perfect account…” questioned, was John Perry. John told Overbury that he had set off for Charrington to meet Harrison the night of the 16th but decided to turn back since he was afraid of the dark, and thus slept on the pavement till he met with Edward the next day. However, after further interrogation, Perry broke, and accused himself, his brother, and his mother––Richard and Joan Perry––of murdering Harrison. He claimed the previous robbery was them as well, and that the night of August 16th, 1660, Harrison had actually returned home, but the three of them caught him by surprise at the gates of the estate, strangled him, robbed him, then dumped his body in the waste pool. No body was ever found, though, and John's mother and brother denied these claims. The only evidence against John was a ball of inkle he dropped, which he claimed his brother used to strangle Harrison. The three Perrys ended up pleading guilty to the charge of robbery but not murder, likely to take advantage of the Act of Pardon and Oblivion, which had just been passed by King Charles II. Nonetheless, a year later, the three were retried and found guilty on the charge of murder and hanged.[8]

William Harrison’s Personal Account

In a turn of events, two years after his disappearance, Harrison returned to Chipping Campden, healthier than ever. According to his account, as written in the latter half of “A true and perfect account…,” he had been on his way back to Chipping Campden when a horseman called out to him and, scared of being hit, struck the animal, which then angered the horseman, who then, along with his two fellow horsemen, kidnapped Harrison. They then threw Harrison in a stone pit, only to pull him out mere hours later, stuff money into his pockets, board him onto a ship to be sold as a slave, and then sailed for six weeks until arriving in Turkey. Once there, Harrison was sold to a Turkish doctor, whom he worked for for 2 years until the doctor's eventual death. Upon his death, Harrison was finally free and set off back to Chipping Campden.[8]

Sir Thomas Overbury and Thomas Shirly

While it’s undeniable that Sir Thomas Overbury was the author of “A true and perfect account…,” it’s a point of contention whether Overbury, as the magistrate of Chipping Campden, was the one who was in charge of the investigation and interrogation of John Perry. If so, this could lead to potential details being excluded from the pamphlet in an effort to paint himself in a better light, which should be kept in mind when reading “A true and perfect account…”

Another important aspect concerning the content of “A true and perfect account…” is in the title of the book. The specific line is “sent in a letter (by Sir T.O. of Burton, in the county of Glocester, Kt. and one of His Majesties justices of the peace) to T.S. Dr. of physick in London,” Sir. T.O., standing for Sir Thomas Overbury, and T.S. standing for Thomas Shirly. What's interesting about this is that this singular sentence frames the entire first part of the pamphlet concerning the trial as a “letter” rather than what one may assume is a direct recounting of the events from Sir Thomas Overbury with the intention of publication. Looking through readily available biographical records, no information could be found regarding a doctor named Thomas Shirly residing in London in the 1660s-1670s. While it can’t be definitively said, this letter format was likely a fabricated stylization choice made to lend more readability and credibility to the pamphlet. This was actually a common tactic during the 1600s,[9] as formatting a story through the guise of a letter helped relay facts surrounding the case to the audience in a more natural and seemingly objective way. If, in fact, fake, the occupation chosen for Thomas Shirly as a doctor shows the author's desire for the story to be seen as objective and factually correct, implicitly emphasizing the notion that because well-respected and educated people are involved in this case, the information provided in the pamphlet can be undoubtedly trusted.

Material Analysis

Substrate

Observing the book based on its most exterior aspects, its outermost binding (i.e., what the pamphlet was re-bound in) appears to be leather complemented with rudimentary gilded edges. Gilded edges are usually added for embellishment purposes, but seeing this is a rebinding, gilded edges could also have been added with the intention of protecting the book from moisture and dust (Source). Analyzing the substrate more closely, fragments of the previous binding can be seen underneath the current one.

Based on in-person analysis of the pamphlet, the original binding (bound in approximately 1676), seems to be made of vellum. The meat of the cover has the thickness and durability attributable to vellum––the original bindings’ signs of aging corroborate this. The binding for the pamphlet itself was likely a simple stitch binding, a common practice for pamphlets and books in the 1600s. The paper of the original book seems to be made from linen or cotton rags––rags being the most used material for paper making during the 17th century.

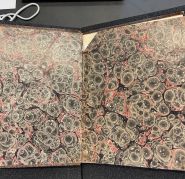

As time passed and possession of this pamphlet transitioned, it is likely that in ~1825, the current owner of the pamphlet saw some form of value in the pamphlet and decided to rebind it. This is evidenced by multiple attributes, such as the rebound cover, modern endpapers watermarked with 1825, and marbled endpapers. These additional endpapers help stabilize the structure of the book, as they’re thicker than the book’s interior pages and serve as a new attachment point for the book’s covers, lessening the stress on the original interior pages, which are very brittle. These additional endpapers look to also be made from some form of linen or cotton rag, as wood pulp had yet to be invented (1843) and rag-based paper was still the norm in 1825.

Moreover, the pamphlet contains distinct marbled endpapers, a popular feature in bookbinding during the 19th century. These marbled endpapers were likely added for aesthetic purposes and to protect the interior binding from wear and tear. These marbled endpapers are unlikely to have been added by the University of Pennsylvania, as libraries tend to focus more on conservation than aesthetic, and thus don’t use decorative paper but rather archival-quality paper.

The rebinding itself speaks to the larger cultural movement taking over 19th-century Europe, antiquarianism. With heightened historical consciousness, nationalism, and an emerging middle class looking to symbolize their newfound wealth, collecting and preserving rare books became particularly pronounced in the 1800s. One can assume that this movement had an influence on the individual responsible for rebinding this copy of “A true and perfect account…”

Format

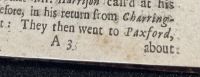

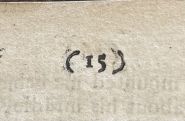

The overall format of “A true and perfect account…” is a 23-page (24 including unnumbered pages) pamphlet, meaning it is also a codex and has a bibliographic format. “A true and perfect account…” can be identified as a quarto by looking at the marks made at the bottom of certain pages (i.e., A3, B, C). For example, A3 is the signature at the bottom of page 3, the next signature, B (synonymous with B1), is listed at the bottom of Page 9, and the final signature, C (synonymous with C1), is listed at the bottom of page 17. This tracks with the quarto format, as gatherings are made up of 2 folds, 2 bifolia, 4 leaves, and 8 pages; thus, the first quarto gathering (A) starts on page 1 and goes to page 8, the second quarto gathering (B) starts on page 9 and goes to page 16, and the third quarto gathering starts on page 17 and goes to page 24 (left blank).

Quartos were the typical format for pamphlets in the late 1600s in England for many reasons, one being their economic nature, as producing them required less paper and much simpler binding than other popular larger formats of the time, like folios. Quartos were also a convenient size, most being around 20 centimeters tall to 15 centimeters wide, which made them easier to handle, distribute, and read––ideal for quick dissemination of information.

Paratext

“A true and perfect account…” does contain paratext, mainly the title page, which is not part of the main body of text itself, but instead serves to help readers frame, contextualize, and interpret the meaning of the text. This paratext was likely not written by Sir Thomas Overbury, as he is a high-ranking government official and would likely not have spent his time penning the paratext to this pamphlet.

“A true and perfect account…” contains many of the common navigation features found in pamphlets during the 1600s. The pamphlet begins with a title page (akin to a foreword), offering the book’s title, which isn’t a single sentence like most modern-day titles, but instead a multi-sentence summary describing the overarching plot of the pamphlet.

The pamphlet is also marked with page numbers (only odd) in parentheses at the top of each recto––the front side of each leaf. Numbering only odd-numbered pages was a common practice during the time, as it helped save resources and made sense for shorter documents like pamphlets which don’t require precise navigation.

At the bottom of each page there is also the first word of the following page, known as a “catchword.” Its main purpose wasn’t actually for the reader, but instead to aid the typesetters in the process of typesetting. Providing this catchword allowed typesetters to quickly verify they were setting the pages in the correct order for the binding process.

The pamphlet is split into 3 distinct sections (excluding the title page): 1) a recapping of William Harrison’s disappearance and the following Perry family’s trial,[10] 2) Sir Thomas Overbury's correspondence with William Harrison (including William Harrison’s letter to Sir Thomas Overbury) and Sir Thomas Overbury’s response to William Harrison’s letter, and 3) an afterword, which after looking at verbiage and other stylistic choices appears to have been written by someone else besides Overbury. These three sections are distinctly separated, each starting on a new page and ending with double black lines while the next begins with these same double black lines. Single lines on pages delineate a change in perspective within the same section (i.e., switching from William Harrison’s letter to Sir Thomas Overbury’s response to his letter). Similarly, there are also subheadings signifying the start of a subsection within a section (i.e., the start of William Harrison’s letter has the subheading “For St. T.O. Knight”).

Text

The text in “A true and perfect account…” was printed using moveable type, the standard method during the 1600s in England. The text on each page is uniform in its alignment and spacing, suggesting that a well-maintained press was likely used to print this pamphlet. However, there are also minor discrepancies in the typeface, such as uneven inking, misalignment in characters among words, and stray ink marks.

This misplaced type, also referred to as shadow letters, can likely be attributed to the ink from previous pages not being fully dried and the printer stacking the newly printed pages on top of the still ink-dampened sheets, thus offsetting specific characters onto other sheets (Source). The sheets are often then shifted and pressed together again, causing this ink to re-offset on the original sheet and other copies. While there are other things that could explain why the text has shadow letters, because the writing is not mirrored and the shadow letters seem to be facing different directions throughout the different pages, it’s likely the offsetting is due to a manual error during handling.

The typeface used for the body of the pamphlet appears to be a typical Roman type, a noticeable difference from the blackletter typeface that characterizes most books from the mid-12th century up until the 17th. The Roman type was inspired by Renaissance humanists who favored clearer and more legible styles of text, and is in stark contrast with Blackletter (gothic) type, which is only used a singular time in “A true and perfect account…,” in William Harrison’s letter to Sir Thomas Overbury when he addresses him as “Honoured Sir.” It’s likely this typeface change was deliberate and served both a stylistic and symbolic purpose. As Blackletter type became less popular in the 1600s, it shifted from being used for entire texts to being used in specific instances to most often emphasize tradition and formality. This makes it appropriate to use in the case, as it shows due respect to Sir Thomas Overbury, a man of high status, and emphasizes the gravitas of the letter.

Marks, Marginal, and Annotations

The book has been written in, but it seems to have been written in by someone more recently, likely an archivist. These annotations are mostly illegible, and while they can not provide us much information about the original use of the pamphlet, one can assume it signifies that there has been some contemporary interest in the subject at hand, an interpretation corroborated by the fact the Campden Murders have maintained popularity, having inspired famous literary works such as John Rhode’s detective novel "In the Face of the Verdict" and E.C. Bentley's "Trent's Last Case." The story has also been adapted into plays by John Masefield, a radio play titled "The Campden Wonder" by Roger Hume, and weaved into a song by the band Inkubus Sukkubus on their 2016 album “Barrow Wake”.

Significance

Insight Into Historical Legal Practices & Reform

“A true and perfect account…” had a significant impact on the justice system[11] when the pamphlet was published. While many aspects of the pamphlet were sensational and sometimes unbelievable, the fact stood that three innocent people had been wrongfully executed, and that’s the antithesis of justice. The release of the pamphlet led to a public outcry, and, as a result, the English courts instituted a new criminal rule: “no body, no murder.” However, this was never an actual law implemented in England (Source), as it would have had too many loopholes (i.e., murderers would be fine as long as they hide the remains of their victims really well). The pamphlet also demonstrates the justice system's reliance on insufficient evidence and possible coerced confessions, catalyzing conversations around these topics for lawmakers, judges, and more.

Social and Cultural Reflection

While “A true and perfect account…” doesn’t make specific mention of social class in the book, it was widely discussed at the time of the pamphlets release and is to this day, the stark differences between how the gentry (the social class the Harrison’s feel into) and the serving class (the social class the Perry’s were apart of) were treated, and how class can affect perceptions of innocence and guilt. While social classes are much less stratified today in most countries, remnants of class-based sentiments remain, “A true and perfect account…” serving as a reminder that to maintain the integrity of justice systems we must treat all as innocent until proven guilty.

Moreover, “A true and perfect account…” provides valuable insight into how the legal system and society treated women during the 17th century, specifically in regard to Joan Perry (John and Richard Perry’s mom). During the time, women, especially women from lower social classes, were highly vulnerable in the legal system, as they were susceptible to baseless accusations, assigned ineffective legal representation, and subjected to scathing scrutiny. Joan Perry herself was from a lower social class and a widow, two things that immediately made people view her with suspicion and easily target her with accusations. Women to this day face similar issues when they don’t perfectly fit the mold of what’s expected of them.

Early Media Influence

The form of “A true and perfect account…” also offers a significant amount of information regarding early media influence and how we can still see the lasting effects of it today. The rise of pamphlets in the 16th and 17th centuries marked a significant shift in how information was shared, and public discourse was fostered, laying the ground with foundational concepts that will eventually progress into modern forms of media. “A true and perfect account…” exemplifies how with the democratization of information, there are many positive aspects (awareness and advocacy, more interactive dialogue, community formation, and more) but also negative things, like the ability for public opinion to fully turn the tide of a life-or-death murder trial.

Overall, “A true and perfect account…” is a rich recounting of a sensational yet real story, which informs us a great deal about injustices faced in the justice systems during the 17th century, and also how pivotal pamphlets were in shaping the world of information dissemination.

References

- ↑ MacMillan, Ken. Stories of True Crime In Tudor and Stuart England. 2nd edition. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2023.

- ↑ Bucholz, R. O., and Joseph Ward. London : a Social and Cultural History, 1550-1750. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- ↑ Lamal, Nina, Jamie Cumby, and Helmer J Helmers. Print and Power In Early Modern Europe (1500-1800). Leiden: Brill, 2021.

- ↑ Cellier, Elizabeth. Reflections Upon the Murder of S. Edmund-bury Godfrey : the Design of Thompson, Farwell, and Paine to Sham Off That Murder From the Papists : the Late Endeavours to Prove Stafford a Martyr and No Traitor, and the Particular Kindnesses of the Observator, and Heraclitus to the Whole Design, In a Dialogue ; with a Dedication From Mrs. Cellier. London: Printed for A.B. and published by L. Curtiss, 1682.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 British Book Trade Index, bbti.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/details/?traderid=57621. Accessed 13 May 2024.

- ↑ Bayman, Anna. Thomas Dekker and the Culture of Pamphleteering In Early Modern London. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate, 2014.

- ↑ Stevenson, Matthew. The Quakers Wedding, October, 24. 1671. London,: Printed for Rowland Reynolds, at the Sun and Bible in the Poultry, 1671.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 . Overbury, Thomas, and William Harrison. A True and Perfect Account of the Examination, Confession, Tryal, Condemnation and Execution of Joan Perry, and Her Two Sons, John & Richard Perry, for the Supposed Murder of William Harrison, Gent. : Being One of the Most Remarkable Occurrences Which Hath Happened In the Memory of Man. London: Printed for Rowland Reynolds, next Arundel-Gate, over-against St. Clements-Church in the Strand, 1676.

- ↑ Raymond, Joad. Pamphlets and Pamphleteering In Early Modern Britain. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- ↑ . "A true and perfect account of the examination, confession, trial, condemnation and execution of Joan Perry, and her two sons, John and Richard Perry, for the supposed murder of Will. Harrison, Gent Being one of the most remarkable occurrences which hath happened in the memory of man. Sent in a letter (by Sir Thomas Overbury, of Burton, in the county of Gloucester, Knt. and one of His Majesty's justices of the peace) to Thomas Shirly, Doctor of physick, in London. Also Mr. Harrison's own account how he was conveyed to Turky, and there made a slave above 2 years, when his master (who bought him there) dying, he return'd to England; in the mean while, supposed to be murdered by his man-servant, who falsly accused his own mother and brother as guilty of the same, and were all three executed for it on Broadway-Hills, in Gloucestershire." In the digital collection Early English Books Online. https://name.umdl.umich.edu/A53577.0001.001. University of Michigan Library Digital Collections. Accessed May 13, 2024.

- ↑ Bar, L. v, and Thomas Sydney Bell. A History of Continental Criminal Law. South Hackensack, N.J.: Rothman Reprints, 1968.