The Boke of Common Prayer (1583?)

The Boke of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments, and Other Rites and Ceremonies in the Churche of Englande is an edition of the Anglican Communion’s Prayer Book, which includes written prayers for specific situations—such as the re-churching of women following childbirth and daily morning prayer—as well as instructions, general prayers, collects for every Sunday in the ecclesiastical calendar, and other such formulas for the celebration of the Mass, and psalms set to musical notation, among other things.

Though the exact print date cannot be ascertained with absolute certainty, it seems to have been printed during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, a devout Protestant. This particular edition is in reasonably fair condition, although it has been rebound poorly, as evidenced by the state of the covers (discussed further below). Conveniently, this book was recently digitized (2022) by the University of Pennsylvania library system. Specifically, the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts at UPenn currently has possession of this version of the BCP.

Background

Authorship of the Book of Common Prayer (BCP)

Thomas Cranmer, leader of the English Reformation and creator of the first vernacular Christian liturgy in English, was a zealous man but a paradoxical one. He married twice, despite his track of study—theology, with the aim of being ordained a priest—and having lost his first wife in childbirth, he married Margarete Osiander. When he was appointed the Archbishop of Canterbury, he hid his second marriage, as priestly celibacy was still the rule in England at the time. He defended the annulment of King Henry VIII’s marriage to Catherine of Aragorn, but when the pope rejected the annulment, the Reformation Parliament declared King Henry to be the head of the English church in place of the pope. Cranmer would have considered this a great victory, as evidenced by this quote of his:

“And as for the Pope, I refuse him, as Christ’s enemy and Antichrist, with all his false doctrine.”[1]

Eventually, after helping to organize the newly independent church, Cranmer completed the first edition of the Prayer Book in 1549 and another version, more explicitly Protestant and Reformed than the first, in 1552. Despite Cranmer’s and King Henry’s questionable marital choices, the Prayer Book has since become not only a keystone of the English language and Reformation, but also a force of a devotional book which is still in use by many today, including the Church of England, the Episcopal Church, and Continuing Anglicans, though the more theologically progressive churches use newer, pared down versions.

Subsequent major editions include the 1559 edition, the 1662 edition, the 1928 edition, and most recently, the 2000 Common Worship series (which is so different from the original that it arguably cannot be counted as a new edition), although there were hundreds of less significant editions made prior to the more significant 1662 edition.[2] Cranmer’s original versions were very Scripturally based; that is, many of the prayers included direct quotes from the Bible in addition to Cranmer’s own written compositions.

Theological content of the BCP

The theological focuses and associations of the BCP shift depending on the edition. This particular BCP is likely one of the hundreds of permutations made between Cranmer’s first two editions and the 1662 edition, so without reading the entire text through, one might do well by supposing that it is more Protestant in emphasis, since the 1559 version was such.

Reading practices

Cranmer’s BCP encourages discontinuous reading—that is, reading which is purposely non-chronological and often gets at particular themes from various areas of a text rather than chronology—similar to the Roman Catholic High Mass missal, which required frequent page-flipping in order to keep up with the service.[3] The BCP puts forth a suggested schedule of Scriptural/liturgical readings for the parishioner to follow throughout the year. For instance, February 1 might include Deuteronomy 3, 1 Timothy 6, and Matthew 20 (with the selected passages dealing with similar issues) rather than, for instance, Deuteronomy 3-6 (which would maintain the structure of the biblical narrative). In this way, it seems to converge with the Roman Catholic missal’s method, but admittedly the early prefaces to the BCP explicitly objected to the Catholic method of frequent flipping, as Cranmer found it to be overly complex.[4] The BCP does accordingly decrease the amount of page flipping that occurs in the Communion service, and its calendar is also simplified—it has reduced the number of saint’s days/holy days.

Theology of music

Cranmer’s conception of the role of music in the liturgy changed as he encountered various theological influences such as Martin Luther and Huldrych Zwingli.[5] Luther “appreciated polyphony, but realised that the most effective way of transforming worship was to include ordinary people in the performance of the liturgy,” thus inspiring him to add congregational hymn into his liturgy. In other words, Luther struck a balance between the two. Zwingli, on the other hand, believed that any form of music or other art could “[distract] the worshiper's mind from God.”[6] Cranmer seemed to have been especially influenced by the Zwinglian approach between the 1549 and 1552 editions, as the provision of music in the BCP decreased with the newer version, though he also visited Germany, the homeland of Lutheranism, and subsequently put out an edition of the 1544 English Litany set to music.[7] Cranmer also suggested that professional musicians rather than the congregation sing the worship music, which is perhaps derived from Zwingli as well.[8]

Generally, the BCP doesn’t speak too much to either approach, and perhaps as a result of these varying opinions on liturgical music, the early editions of the prayer book do not prescribe one specific way to go about singing in church—this has contributed to the vast and rich variety of worship music in Anglican hymnals today, which often include everything from canticles to musical psalm settings.[9]

Theology of prayer

According to scholar Rachel Targoff, Anglicans thought that the outward, communal practice of prayer, alongside a personal comprehension of and response to what is being said, had the ability to move someone closer to God—whereas Catholics thought that the Mass was largely reserved for only priests’ understanding, meant to inspire individual devotion separate from the progression of the service.[10] One illustration of this is the general confession in the BCP service as opposed to the secret, individual confession associated with the Roman Catholic one.

The BCP, as it is in the vernacular of the English peoples rather than in Latin, like Catholic Mass, was intended to partially break down the Catholic barrier between the celebrant and the laypeople, making Mass a much more congregational event if celebrated according to the BCP.

Material/substrate analysis

This edition has very sturdy paper, with relatively little degradation over the hundreds of years it has been around. Moreover, it was probably in active use, or in the possession of one family, perhaps, for almost 100 years, given the dated note in the back and the likely print date (see signatures & missing pages section below). There are several pages, however, which have been mended by later patching.

Signatures & missing pages

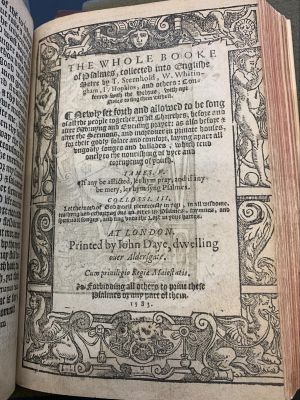

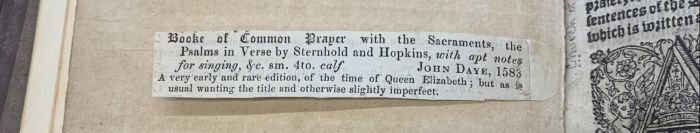

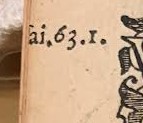

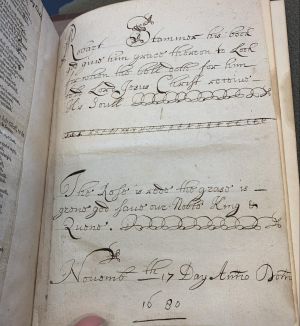

This version of the BCP is missing several pages in the front, including the title page. This is not only evidenced by the little pasted-in scrap of paper functioning as a title page, but also by the fact that the first few letters in the folio-labeling system are missing (the A-signature pages and some of the B-signature pages). Because of this—and also because this version has been rebound at some point—its print date cannot be ascertained, though several factors point to 1583. For instance, the scrap of paper someone pasted in could very well be a piece of the original title page or perhaps a slip cut from an auction catalog by either the bookseller or buyer to identify the book. This slip indicates that the book was printed in 1583. Furthermore, there is a piece of paper inserted in the back of the book handwritten and marked with the date 1680 (see below section on flyleaves), indicating that the prayer book was at the very least printed prior to then. Presuming that this copy was indeed printed in 1583, this would likely make it quite rare, as the very first edition of the BCP was printed less than 40 years before in 1549.

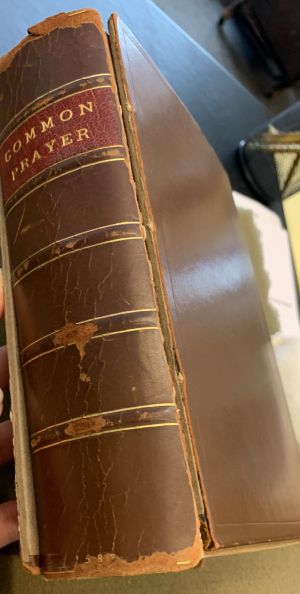

Exterior

The book appears to have been cut down in rebinding, as many of the verse citations in the margins have been cut into. The rebinding is poor—the covers have fallen completely off of the rest of the binding—and it is now slightly more squat than the size of an average contemporary paperback. Again, the foliation begins with B4, and it ends with Kk4, with eight pages to each letter group. One might think that this would indicate that the book is an octavo, but it is too large to be an octavo, so it is probably a quarto that has been set into gatherings of eight.

Flyleaves

On a piece of paper at the back of the book, clearly inserted after printing, a man seemingly named Robart (sic? Perhaps Robert?) Stammos. There seems to be a line of either doodling or practicing writing letters, which may make sense, because the handwriting is unsteady/irregular enough to be a child’s or that of someone just learning to write. At the bottom of the note, he lists the date (“Novemb. th17 [sic]… 1680”). Perhaps this book was passed down from father to son, or in some other manner through the generations of a family. Regardless, the book was still in some form of use almost a century after it seems to have been published.

Interior/format

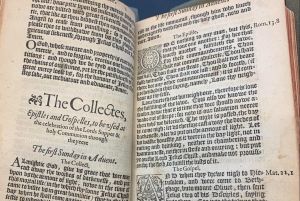

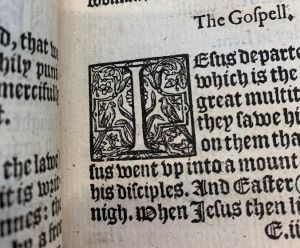

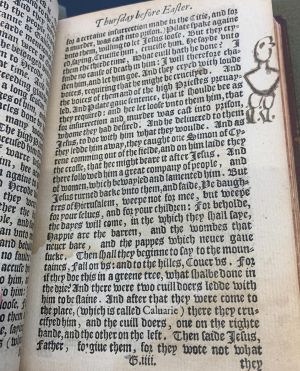

Small, likely wood-cut, illustrations often surround the first letter of paragraphs or sections, and such illustrations include woodland creatures and/or line designs. As might be expected of the time period, most of the text is in a gothic font, but some clearly significant words are in a roman font. These words include linguistically unique phrases (e.g. “Eli, Eli, lama-sabachthani,” (fol. f2r) which some of are Christ’s final words on the cross, but also generally significant words and phrases, like “Calvarie” (fol. g4r) and “Jesus the King of the Jewes” (fol. f2r) are also set apart in this way. The pages are edged with a burgundy color, now faded with time and/or use.

Printing of the BCP

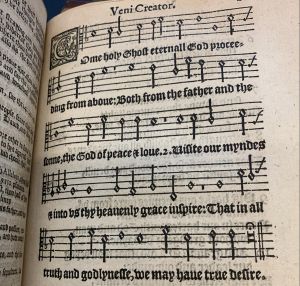

The standard moveable type printing press, which at this point would have been in regular use, would have been used for most of this book. However, there is also printed musical notation in the psalms section of the book after most of the rest of the content. Printing musical notation smoothly was a challenge in the 16th century, as printers had to individually set each of the notes, which were each attached to their own staff lines. This “single-impression method,” created by John Rastell, is why, if one looks closely, one can see small breaks in the staff lines between notes of this BCP.

Reading

The 1549 BCP would have been widely circulated among English churches and parishioners, as the Act of Uniformity of 1549 required that the book be in use by the feast of Pentecost in all churches in the country, meaning that it was the only legal text governing Christian worship at the time of institution. The 1552 BCP, however, was only in use for a year before Mary I ascended to the throne and reinstituted Roman Catholicism to England, therefore largely quashing its production.

Evidence of readership/use

There is evidence of use on several of the pages (including the back flyleaf, again, as mentioned above in the flyleaf section), on which an owner seems to have doodled. Most are abstract images, but one on fol. g4r can be identified as a human figure.

According to scholar Evelyn B. Tribble, Protestant marginalia/commentating practices were generally less prescriptive than their Roman Catholic counterparts, because some Protestant theologians viewed the Catholic “medieval Gloss… [as] a convenient symbol of scholastical obfuscation and ecclesiastical duplicity.”[11] Despite this, Reformers like William Tyndale did still add marginalia/commentary of their own.

The marginalia in this case is certainly of no serious tenor. It looks like a child’s distracted doodle or something absent-minded of the sort—it doesn’t seem to provide any further context or theological interpretation of the text.

Significance for book history & its historical moment

The Boke of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments, and Other Rites and Ceremonies in the Churche of Englande was still theologically and culturally revolutionary for its time. It helped to continue solidify the English Reformation, and demonstrates the relative ease with which printers could mass produce books at this point, given that all churches, if not all literate parishioners, should in theory have been given or purchased a copy during the time when Anglicanism was the only legal denomination of the land.

It also demonstrates a wide variety of content—such as Scriptural readings, a calendar, and psalms—and techniques, including, interestingly, musical notation. This book perhaps demonstrates better than any other what the ubiquity of the printing press can help to accomplish: widespread cultural and religious shifts, alongside spreading literacy and complex representation in print.

- ↑ Thomas Cranmer (1833). “Remains”, p.140, see https://www.azquotes.com/author/32090-Thomas_Cranmer.

- ↑ Maltby, Judith, Prayer Book and People in Elizabethan and Early Stuart England.

- ↑ Stallybrass, Peter, “Books and Scrolls: Navigating the Bible,” Books and Readers in Early Modern England.

- ↑ ^Stallybrass, "Books and Scrolls".

- ↑ Bethke, Andrew-John, “The Theology Behind Music and its Performance in Anglican Worship: An Historical Exploration of Anglican Theological Attitudes to Music, Starting With the 1549 Book of Common Prayer and Finishing With An Anglican Prayer Book 1989”.

- ↑ ^Bethke, "The Theology Behind Music," 47.

- ↑ ^Bethke, 49-50.

- ↑ ^Bethke, 50.

- ↑ ^Bethke, 53.

- ↑ Targoff, Introduction of Common Prayer: The Language of Public Devotion in Early Modern England.

- ↑ Tribble, Evelyn B. “Authority, Control, Community: The English Printed Bible Page from Tyndale to the Authorized Version.” Margins and Marginalia: The Printed Page in Early Modern England, 16.