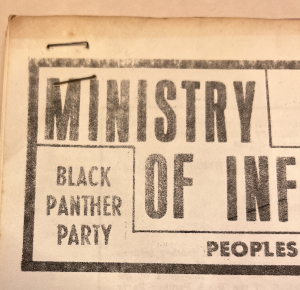

The Black Panther Ministry of Information

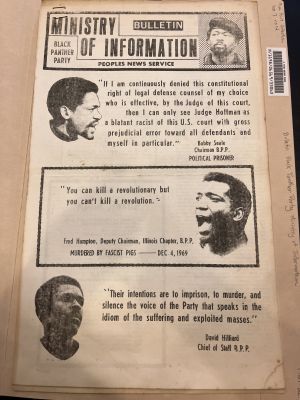

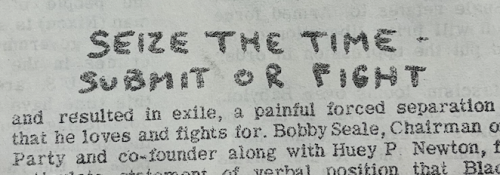

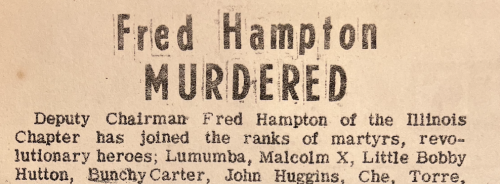

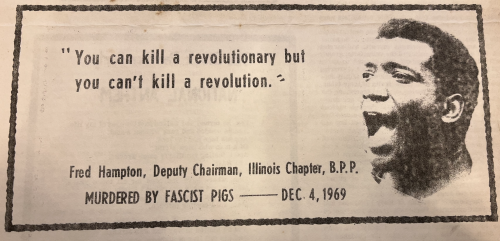

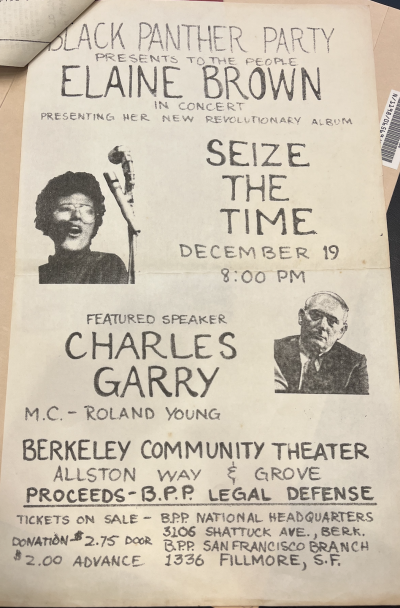

The Black Panther Ministry of Information Bulletin is one of the newspapers provided by the Black Panther Party Oakland Branch. This copy was purchased in 2022 from Lorne Bair Rare Books. This particular bulletin is the December 1969 Issue highlighting recent events such as the murder of Fred Hampton. This bulletin includes a variety of information ranging from quotes from Black Panther members, to an imprint of The Black Panther Party National Anthem, to a handwritten poster for an Elaine Brown concert.

Background

The Black Panther Party of Self-Defense was founded in Oakland, California by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale in 1966. Newton and Seale founded the The Black Panther Party with the momentum following the unrest resulting from the assassination of Malcolm X and killing of unarmed Black teen Matthew Johnson. Known to be dressed in black berets and black leather jackets, The Black Panther Party at first sought to surveil and challenge police brutality. Quickly, The Black Panther Party expanded into a nationwide initiative that provided social programs for many minority groups besides Black people. The Black Panther Party became a force that could unify communities together.[1]

Politically and socially, The Black Panther Party is known historically as a Black nationalism movement. Jessica Harris describes well in her article “Revolutionary Black Nationalism: The Black Panther Party” how socially “Black nationalism deals with the proposition that an oppressed people must first cherish a friendly union with themselves , and that this particular charity begins at home and then spreads abroad.”[2] Harris then goes on to outline the political objective: “Black nationalism can range from the admonition that Black people must control all the politics and economics of their communities, to the creation of a separate Black nation in North America or returning to the African homeland.” [2] Evidenced by Harris’ definitions, Black nationalism is not so easily defined, and The Black Panther Party does not represent the sole type of Black nationalism in America. This Bulletin, in particular, illustrates the aims and effects of The Black Panther Party.

One of the primary methods of spreading information and recruiting new members was through the The Black Panther Bulletin. Eventually, The Black Panther Bulletin became a widely read newspaper to provide a counter perspective to the ongoing portrayal of Black people as inferior and deserving lesser treatment. In Jessica Lipsky’s “The enduring influence of the Black Panther Party Newspaper,” Lipsky says that The Black Panther Newspaper not only had external impact but internal effects as well: “The Black Panther acted as an economic support system for the rank-and-file members: each issue was sold for 25 cents, of which sellers kept 10 cents.”[3] Lipsky also references the paper’s use of recruitment: “Panthers who sold the paper spread the Party’s message and encouraged new people.” The Black Panther Party Newspaper served as a powerful source of recruitment, inspiration, and community building.[3]

Physical Analysis

Place

The Black Panther Ministry of Information Bulletin was made in San Francisco, California as provided by the red tag stapled to the end of the newspaper. The red tag reads “Ministry of Information, Black Panther Party, Box 2967, Custom House, San Francisco, CA 94126.” Additionally, the bottom of the Elaine Concert post shows an address to the “B.P.P. National Headquarters.”

Publisher and Copyright/Licensing

A red subscription form stapled to the back of the newspaper shows the licensing of this newspaper made by The Black Panther Party. The newspaper was “published weekly” officially by the Black Panther Party and could be sent internationally.The subscription form at the back of the newspaper and printed titling at the front of the newspaper exhibit the licensing as well.

Substrate

The newspaper itself is made from some sort of reinforced paper that is thicker and larger than normal pieces of paper. The newspaper is a mixture between cut out individual letters, copy and paste photos, and handwritten titles and posters. Offset printing would be the typical mode of printing for a newspaper like this where the individual would have separate sheets of paper, each with the typed portion or handwritten portion. Then, the whole newspaper would be printed together. Jana Iverson in “The Offset Printing Process: How it works” states, “Offset printing or offset lithography is a printing press technique that transfers the ink from a plate to a rubber roller (or blanket) and then to various substrates to produce high quality images and designs.”[4] The subheadings of the articles highlight well the contrast between the typed and handwritten portions of the newspaper.

Platform/Format

This book can be described in various ways such as protest literature, a periodical, or a bulletin. The most accurate format is a bulletin because of the mixture of mediums such as typing and handwriting to make the newspaper, the readability, and few pages of information. The presence of fiery quotes and a concert poster also suggest the platform of a bulletin. Given the usage of this text, the bulletin helps well with spreading news, bringing in new members, and generating uproar.

Binding/Structure

This bulletin has stapling in the top-left hand corner which lines up well with the time of this issue, 1969. For a bulletin, stapling provides for easy binding of the large pages, and the stapling makes it easy for Black Panther members to hand out the newspaper on the streets. The physicality of handing out each bulletin to prospective members lens to stapling for easy-readership and passing along.

Marginalia / Annotations

This bulletin is completely free of any marginalia, annotations, or marks suggesting that bulletin was not meant to be actively engaged with at a high level. The Black Panther Party may not have been intending readers to analyze the text but to quickly take in the information. The bulletin is short and delivers strong language and information succinctly for the reader to understand the material in a fast manner.

Paratext

The red subscription form pictured earlier is a paratext of the newspaper indicating the ownership of The Black Panther Party which is the same as the author of this text. The subscription form includes blanks for name, address, city, state, and zip code which show the far outreach of this newspaper across the country.

The Role of Printing

The introduction of offset printing allowed for The Black Panther Bulletin to catalyze The Black Panther Movement. Offset printing provided the technology for The Black Panther Party to spread information quickly, cheaply, and broadly. With the meteoric rise of The Black Panthers, the FBI put their resources together to politically repress The Black Panthers. In Charles Jones’ “The Political Repression of The Black Panther Party 1966-1971 The Case of the Oakland Bay Area,” Jones quotes Goldstein’s definition of political repression, ‘“government action which grossly discriminates against person or organizations viewed as presenting a fundamental challenge to existing power relationships or key governmental policies, because of their perceived political beliefs.”[5] In the case of The Black Panthers, the FBI was extremely adverse to any language regarding the equality or equity of Black people especially by a group that believed in using violence to achieve Black retribution. The FBI’s extreme efforts to dismantle The Black Panther Party show how fearful America was to have Black people with the same rights and respect as white people. At the time, the general public did not believe that the FBI had such a strong role in ending The Black Panther Movement. However, Jones references the amount of current evidence of the FBI’s involvement which makes the FBI’s significant involvement an indisputable claim. Evidence such as “public statements made by key government officials” confirm the FBI’s political repression of The Black Panthers.[5] All in all, The Black Panther Party exhibits one example of how printing can catalyze a revolution even to the point of getting the FBI's full attention and force.

Ephemeral Qualities

Having access to such an ephemeral piece of text and kept in good condition is not incredibly common. In recent years, the country has taken greater interest in The Black Panther Movement as the public became more knowledgeable about the FBI’s involvement and the Black Panther's broader role as an organization besides inciting violence. In an article published by The Museum of Modern Art, Akili Tommasino mentions just one of the appealing aspects of keeping The Black Panther: “The selection of papers documents a particularly compelling period in the history of the Black Panther Party and covers major events including the 1969 assassination of Illinois chapter chairman Fred Hamption.”[6]Tommasino even regards his stewarding of The Black Panther as a “privilege.”[6] Tommasino’s excitement to steward the 30 issues acquired by MoMA shows a sliver how much people covet and care for something as ephemeral as one copy of the many copies of The Black Panther Bulletin.

Significance

Documents such as this newspaper provide a window into time of the events concerning the Black Panther Party and how they functioned. Bringing to light and analyzing texts such as this bulletin, broaden the audience’s perspective on The Black Panther Party and its complexity. Rhetoric surrounding Black Panthers typically limits them to just “violent thugs” as Joe Street mentions that other historians do in his “The Historiography of the Black Panther Party.”[7] By taking the time to parse through this newspaper, the limiting and one-dimensional perspectives of The Black Panthers can be challenged. Furthermore, the modern influence of activism from the Black Panthers can be observed with the language such as pigs and twitter-like quotes that inspire readers to act quickly and stand up for a cause.

References

- ↑ Editors, History.com. “Black Panthers - History, Definition & Timeline.” History.Com, 2023, www.history.com/topics/black-history/black-panthers.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Harris, Jessica C. “Revolutionary Black Nationalism: The Black Panther Party.” The Journal of Negro History, vol. 86, no. 3, 2001, pp. 409–21. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1562458. Accessed 8 Apr. 2023.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Lipsky, Jessica. “The Enduring Influence of the Black Panther Party Newspaper.” Columbia Journalism Review, 2019, www.cjr.org/analysis/history-black-panther-newspaper.php.

- ↑ Iverson, Jana. “The Offset Printing Process: How It Works.” PakFactory Blog, 5 May 2023, pakfactory.com/blog/what-is-offset-printing/.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Jones, Charles E. “The Political Repression of the Black Panther Party 1966-1971: The Case of the Oakland Bay Area.” Journal of Black Studies, vol. 18, no. 4, 1988, pp. 415–34. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2784371. Accessed 8 Apr. 2023.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Tommasino, Akili. “Black Power in Print: The Black Panther Newspapers at Moma: Magazine: Moma.” The Museum of Modern Art, 2021, www.moma.org/magazine/articles/641.

- ↑ Street, Joe. “The Historiography of the Black Panther Party.” Journal of American Studies, vol. 44, no. 2, 2010, pp. 351–75. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40648818. Accessed 8 Apr. 2023.