The Aldine Psaltērion

The Aldine Psaltērion is a Septuagint psalter printed around 1496 in Venice, Italy by Aldus Manutius. The text is printed in Greek in the tradition of the Septuagint and is representative of the mission of the Aldine Press to preserve and protect Greek classics from the degradation of translation.[1]

Printed with great attention to detail, the text is a quarto featuring several intricate woodcut block prints and dual-toned Gk 146 type. The codex is fully bound in brown morocco with boards tooled in gold and blind. The Aldine Psaltērion is dated too early to have Aldus Manutius’ well-known printer’s mark of the dolphin and anchor. However, there are many other details in this edition including a red leather bookplate with gold-stamped monogram ("CKC") of Charles C. Kalbfleisch (1868-1943) affixed to the front pastedown to signify that that the codex was collected and kept within the special and rare book collection of Kalbfleisch prior to the University of Pennsylvania Libraries acquiring ownership of the text.[2]

The Book

Book Design

The Aldine Psaltērion takes a codex form. The text comes contained in a half brown morocco slip-case with the title and imprint stamped in gold capital letters on the 5 raised band spine (“PSALTERIUM GRAECUM” below the first band, “VENETIIS ALDUS” below the second band). The codex itself is a quarto fully bound in brown morocco with boards tooled in gold and blind. On the left board, the title and imprint is stamped in gold in capital letters ("PSALTERIUM. ALDUS. VENETIIS."). On the spine of the codex there are 5 raised, gold-ruled bands and the spine panels are tooled in gold and blind. Internally, there are vellum paste downs, free endpapers, and gilt edges. Based on the condition of the text and the elaborate aesthetic elements, it is speculated that the book was most likely rebound by the late collector Charles C. Kalbfleisch.

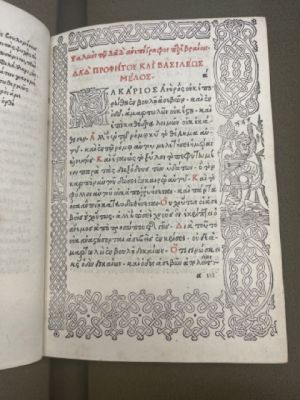

The typeface of the text marks it as a product of the Aldine Press. The text is a liturgical psalter printed completely in Greek characters using the 146 Gk typeface. Black ink is used throughout the body of the text and the first letter of each verse and headings are printed in red ink. On the opening page of the main text (AIII), a woodcut ropework border is printed from four blocks, the lateral blocks incorporating a rabbit and David playing his harp in reference to stories included in the Book of Psalms. Additionally, there is a red leather bookplate with gold-stamped monogram ("CKC") of Charles C. Kalbfleisch (1868-1943) affixed to the front pastedown. Finally, it is important to note that this edition does not contain the Manutius printer’s emblem of the dolphin and anchor as it is dated too early to contain the mark which Manutius only began printing in June 1502.[3]

Print Date

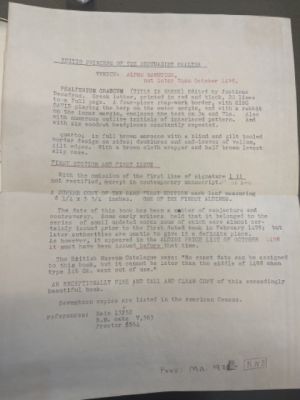

The text is confirmed to be an incunabulum, meaning it was printed before 1501. The print date is identified as 1496 in the Penn Libraries Aeon system; however, there is a greater debate over the date of this text which is not evident from online cataloging. With this edition of the text comes a slip of paper folded inside the cover which further details the debate over the exact print date of the text. Due to the use of type 146 Gk, The British Museum Catalogue claims:

“No exact date can be assigned to this book, but it cannot be later than the middle of 1498 when type 146 Gk went out of use.”

Additionally, this text appeared in the Aldine Price List of October 1498 at the relatively low price of 4 marcelli (about a third of a ducat). This listing further confirms the print date cannot be later than October 1498. The preface of the text is printed in Aldus' second type (a reduced version of the first), in use from August 1496. However, according to the document provided with the text:

“Some early writers held that it belonged to the series of small undated works some of which were almost certainly issues prior to the first dated book in February 1495”.

The Septuagint

History of the Book

The Septuagint is the earliest extant Greek translation of the Old Testament from the original Hebrew. Historians estimate that the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, also referred to as the Torah or the Pentateuch, were translated in the mid-3rd century BCE while the remainder of the translation was completed in the 2nd century BCE.[4] This was at the height of the Hellenistic period and Greek was the most common language in the North African region where there was a large Alexandrian Jewish population. The Greek translations of original Hebrew scripture were in wide use at this time due to the waning Hebrew literacy of the Second Temple period. The specific translation printed by Manutius is called the Septuagint because the legend is that the Hebrew Bible was translated by 72 Jewish scholars from the Twelve Tribes of Israel at the request of Ptolemy II Philadelphus. [5]

Renaissance Revival

Although the Septuagint is quite an old translation of an even older text, there was certainly readership for this text in Manutius’ time. Manutius is printing in the 15th century which many scholars consider to be the height of the Renaissance. The Renaissance was a period in European civilization characterized by a surge of interest in Classical scholarship and values following the cultural decline and stagnation of the Middle Ages. This era was dominated by Humanist thought and a revival of Classical antiquity. The intellectual movement of Humanism was marked by a shift to scholarship led by secular men of letters rather than by scholar-clerics connected to the Church. Renaissance Humanism first began as a movement in Italy in the 15th century when the collapse of Constantinople in 1453 drove eastern scholars to the West. These scholars bought valued manuscripts of Greek scholarship with them and signaled a rebirth of the classical human spirit which was lost to civilization in the Middle Ages.[6]

Despite the Humanist emphasis on breaking from religious orthodoxy, Humanist scholars had an interest in reading the valued Septuagint psalter in order to better understand Classical society and inspire inquiry into the ways of civilizations that came before the Middle Ages.[7] Manutius certainly took this into consideration and his choice to print the Aldine Psaltērion at his print shop in Venice, not too far from the heart of the Renaissance in Florence, was a significant contribution to the scholarship of the era. Even with this rich history, the edition of the Aldine Psaltērion which is now in the collection of the Kislak Center is in such pristine condition that it was most likely collected for its value very early in its lifetime rather than widely circulated and consumed by readers.

The Aldine Press

Manutius' Mission

At his print office based in Venice, Italy, Aldus Manutius prioritized printing Greek classics. Educated in Rome, Manutius expanded his language knowledge from Italian and Latin to also encompass Greek by working with Battista Guarino. Manutius wished to learn Greek so that he could understand the Greek texts from Aristotle, Aristophanes, and other renowned writers in their pure form, untainted by translation. Manutius felt that translation of these texts into Italian, Latin, or any other language would compromise the original meaning intended by the author or authors.[1] In order to effectively print Greek editions, Manutius hired scribes to design and cut typefaces. The most well-known Aldines are the Humanist typefaces and the italic typeface which the Aldine Press first used in a woodcut of Saint Catherine of Siena in 1500.[8]

The Aldine Press revolutionized the printing industry from its start in 1494 because Manutius set out to print lower cost editions. Additionally, Manutius was the first to issue printed books in the small octavo size intended for portability and ease of reading.[9]

Counterfeiting

Today, Aldus Manutius is well known for his iconic printer’s device, the dolphin and anchor. The printer’s device shifted the printing profession as the design often served as something of a trademark. There were several economic motivations behind integrating the printer’s emblem and Manutius, who was revolutionizing printing through his unique editions and typefaces, was quite concerned with piracy. Manutius essentially had a monopoly on works printed in Greek within the Republic of Venice; however, protection of his texts outside the Republic proved to be very difficult as there were no solid copyright laws at this time. As the Aldine Press grew in popularity and prestige, Manutius went as far as including warnings aimed at those who might attempt to create counterfeit versions of his texts. One such warning was:

"no one is allowed to print this without penalty”

which was printed in his edition of Sylvarum libri quinque. Manutius was not entirely successful in this effort because the counterfeiters would simply improve their craft and continue to produce counterfeit editions, predominantly in Lyons.[10]

Special Collection

Charles C. Kalbfleisch

Prior to the Aldine Psaltērion entering the Incunables collection at the Kislak Center for Special Collections, the book was most notably in the personal collection of Charles Conover Kalbfleisch. Kalbfleisch, born in 1868, was a second-generation Dutch-American based in New York City. The Kalbfleisch family had been a prominent family in the New York Metropolitan area since Charles' grandfather, Martin Kalbfleisch, had founded a booming chemicals manufacturing business in the 1830s and was later heavily involved in city politics and financial institutions. Charles C. Kalbfleisch pursued a career in law and received his Juris Doctor from Columbia Law School in 1893.[11]

Outside of his law career, Charles C. Kalbfleisch was a celebrated bibliophile and a committed member of the Grolier Club. The Grolier Club ss a private club and society of bibliophiles in New York City. Founded in 1884, it is the oldest existing club of its kind in North America. Over his lifetime, Kalbfleisch built an extensive collection of special books which included the Aldine Psaltērion and many other valuable texts. Kalbfleisch certainly perceived the Aldine Psaltērion to have immense value due to the great renown surrounding Aldus Manutius and the Aldine Press. Kalbfleisch's ownership of the text is memorialized by the red leather bookplate with gold-stamped monogram ("CKC") affixed to the front pastedown of the book.[12]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Bühler, Curt F. "Aldus Manutius: The First Five Hundred Years." The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 44, no. 3 (1950): 205–15.

- ↑ Penn Libraries Franklin Catalog."Psaltērion." Kislak Center for Special Collections - Incunables.

- ↑ Wolkenhauer, Anja and Scholz, Bernhard F. "Typographorum Emblemata: The Printer’s Mark in the Context of Early Modern Culture." Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Saur, 2018.

- ↑ Mulder, M. J."Mikra : text, translation, reading, and interpretation of the Hebrew Bible in ancient Judaism and early Christianity." Phil.: Van Gorcum. p. 81. 2018.

- ↑ "Septuagint." Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved May 4, 2022.

- ↑ "Renaissance." Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved May 4, 2022.

- ↑ Kallendorf, Craig. "Introduction to Humanist Educational Treatises." Cambridge, Massachusetts and London England: The I Tatti Renaissance Library (2002).

- ↑ "Type to Print: The Book & The Type Specimen Book." Columbia University Libraries Online Exhibitions.

- ↑ Barolini, Helen. "Aldus and His Dream Book." New York, New York: Italica Press, Inc, (1992). ISBN 0-934977-22-4.urgh: Privately Published.

- ↑ Goldsmid, Edmund. "A Bibliographical Sketch of the Aldine Press at Venice: 3 Volumes." (1887). Edinburgh: Privately Published.

- ↑ Weeks, Lyman Horace. "Prominent Families of New York: Being an Account in Biographical Form of Individuals and Families Distinguished as Representatives of the Social, Professional and Civic Life of New York City" (1898).

- ↑ "Grolier Club." Grolier Club. Retrieved May 4, 2022.