Mayan Medical Receipts and Spanish Translation

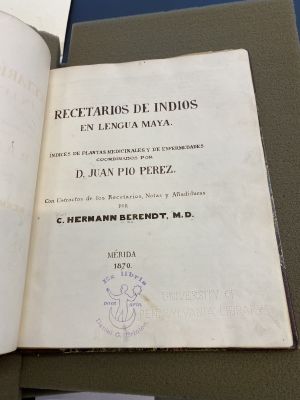

Travel to the 6th floor of the Van Pelt Library at the University of Pennsylvania and venture into the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts to find a compilation of receipts, translations, and other observations that peak into the way of life followed by the Mayans in the Yutacán Peninsula in the 19th century. The collection of these documents composed in a book are in Spanish or Mayan translated between the two languages. When the title is translated to English, it reads, Indian Receipts in the Mayan Language Indexes of Medicinal Plants and Diseases.[1] Much of the content in the book is authored by Juan Pío Pérez. However, the book itself was constructed and written by Carl Hermann Berendt, M.D.

Multiple Authors

Juan Pío Pérez, who originally authored the original source that this book is a copy of, was a Mexican philologist and researcher of Mayan civilization in the Yucatán Peninsula during the 19th century. On the inside title page of the book, it reads “Mérida 1870,” which is most likely the publishing city and year. In the context of Pío Pérez, the publishing city’s significance stems from the fact that he grew up in this city located in Mexico and was mayor of it between 1848 and 1853. Its location allowed him to have easier access to study the Indigenous people that resided in Yucatán. In the original source that Pío Pérez, he was studying the medical information composed in the Books of Chilam Balam, which were a series of texts produced by the Mayans containing traditional knowledge of a variety of aspects defining their civilization. These aspects included history, medicine, religion, and many other things.[2] Many of these types of sources, like the Books of Chilam Balam and a series of manuscripts called “Libros del Judío,” were actually an attempt for indigenous groups, like the Mayans, to preserve their history by switching from oral tradition to a more written one.[3] This could have also been the reason that Pío Pérez decided to replicate the medical information in his research, as his work accounts for languages that do not even exist in today’s world.

The original information documented by Pío Pérez was later copied by Carl Hermann Berendt, M.D., a German-American physician who went on to study natural sciences and Mesoamerican linguistics in Yucatán. He relocated to the United States after leaving Europe and gave up medicine altogether to pursue this passion.[4] This formulated his purpose for creating the book currently being analyzed. However, he additionally contributed his own notes, receipts, and extracts throughout the entire book along with copying what Pío Pérez had already written. As a copy, it is interesting to think about if Berendt copied all of the information in the original source produced by Pío Pérez or only certain things. This is his own book, after all. It is entirely possible that he only copied the information he believed was necessary to relay. However, because of the loose structure of the book and his goal to add more information than what was already present, it may be more probable that he did not choose to leave things out. In the documents he produced, he also did at one point copy extracts from two specific manuscripts from the Books of Chilam Balam (of Mani and Oxkutzcab),[5] so this could also indicate that he wanted to include all that he could in his own collection.

On the inside title page, Berendt’s first initial, “C,” contains a clarification in pencil that says, “Karl.” It may be that he fixed his own name on a title page that he had someone else create for him. On the other hand, the opposite may have occurred where someone wanted to specify that his name could be spelled that way since many online sources conform to the clarification’s spelling.

From Provenance to Kislak

It is apparent that the information in this book first emerged through Pío Pérez’s work and was later transferred into Berendt’s assembly of the book itself. The book eventually reached its current destination at the Kislak Center. But, how did it get there? On the front inside cover, there exists a label pasted onto it that states in an emblem, “Library of the University of Pennsylvania.” Below that, it reads, “The Daniel Garrison Brinton Library.” On the inside title page, there is a stamp that reads, “Ex libris / pace arin / Daniel G. Brinton,” with a man standing on an u-shaped moon holding a star.

Daniel Garrison Brinton was a prominent anthropologist who was foundational in the creation of modern American anthropology. At one point, he donated his personal library collection to the Anthropology Library of the University of Pennsylvania.[6] His library consisted of manuscripts that contained valuable information of rare linguistic materials and other resources, which he bought from Berendt and had become one of the most prominent components of his library. Much of his work did not become published but instead was transferred to museum libraries at Brinton’s request after he received ownership. The library of the University of Pennsylvania holds 183 of Berendt’s entries consisting of over 40 indigenous languages (many of them scarce or completely extinct) within Mexico and Central America from the middle 16th century to the late 18th century. It mainly holds manuscripts and miscellaneous notes that Brinton was initially interested in using for his own research.[7]

Materials Analysis

Initial Physical Observations

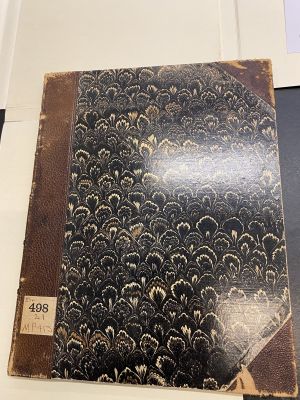

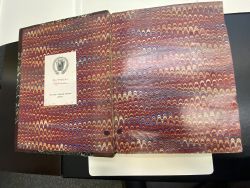

The outside cover is coated in an ornate, floral-like pattern that is colored black, white, and gold. It is a hardcover book, and the pages on the inside cover are different from the rest of the pages in the book. It is bordered on the outer corners with a brown leather cover. The binding itself is made of the same brown leather material and credits Berendt as the book’s creator in gold lettering. The Penn Libraries database refers to it as “late 19th-century half leather.” When opening it to the inside cover, the pattern on the paper is similar, but it looks more like rows of waved lines overlaid one on top of the other rather than the floral pattern of the outside cover, which looks like rows of petals overlaid upon one another. The inside cover also has different colors than the outside cover, which actually holds more variety (blue, red, yellow, green, and white are the main colors that jump out at you). Furthermore, the inside title page itself is a pen facsimile. From the title and authors to the publishing year and city (“Mérida 1870”), everything was handwritten by the maker of this book. Looking closely at the lettering, it is obvious that there are many stroke marks and pencil outlines that indicate the font is written as a manuscript and was not printed.

- Binding of Indian Receipts in the Mayan Language Indexes of Medicinal Plants and Diseases

-

Leather Binding

-

Inside Stitched Binding

-

Glued Binding

Assembly and Readership

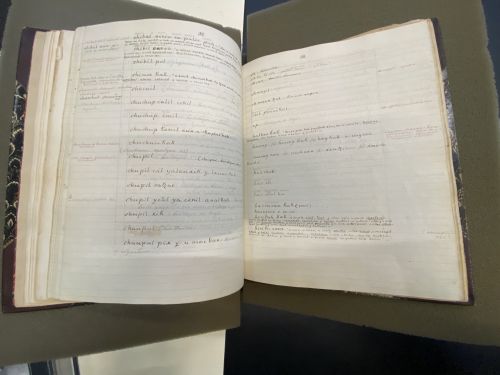

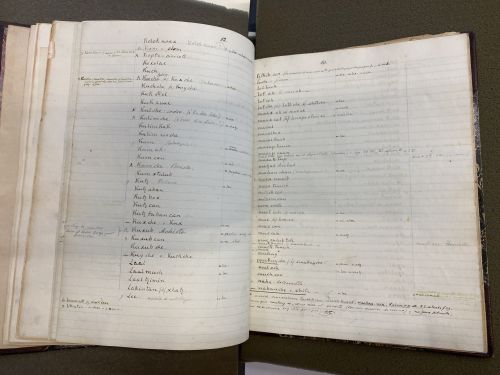

The front pages seem like they are machine-woven paper. However, flip further and you encounter mostly ruled notebook paper. Flip even further, and the ruling of the notebook paper gets gradually larger by the end. The notebook paper in particular is unevenly stitched to the binding. Some of the inner pages that are not notebook paper are also very loosely glued together at the binding site, as well. This has contributed to the fragility of the book, as the pages seem like they could easily rip with one forceful flip. All of these pages seem as if they all come from different sources that Berendt possessed. The time that these additions were crafted could have been before or after the content was copied from Pío Pérez. If all of this information was created before the cover and the machine-woven paper that states the title, then perhaps Berendt later agreed that it would make more sense to compile all of his findings into a single book. If the information was created after the cover, then there may have been a chance that he completely intended to use all of these notes and additions as content for his book initially.

- Inner Notebook Paper Pages

-

-

-

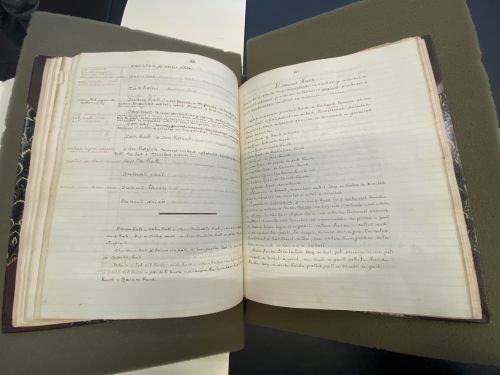

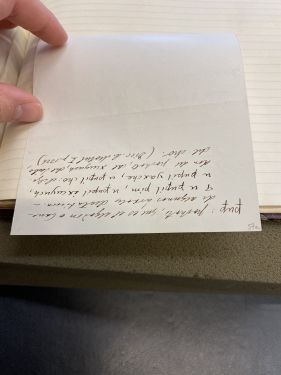

Within the pages, there exists written text primarily in darker, blackish ink. It also has hints of green ink, red ink, and pencil, which can be mostly seen in the margins, as footnotes, and as clarifications. From this preliminary evidence, it seems that this ink was added in after the darker ink that holds the main information. It most likely would have been from Berendt adding to it himself since the book’s history only changed ownership from him to Brinton. However, Brinton could have also added to the book in this manner since his intention was to use it for his research. Mainly in the second half of the book on some pages, there are smaller pieces of paper that hold writing and have glue marks on the other side of the pages they stick to. Some use an interactive interface where the reader must flip them open to see the information. But some contain more written information on the side that is glued and can only be seen when lifting their edges. This demonstrates that these were created before the book and not during the book’s formation. The side that is glued down to the page also could be hiding irrelevant information that Berendt did not think was important for the audience. It could otherwise have been unintentionally hidden with information that Berendt felt he could sacrifice solely to include the smaller pieces of paper if he bothered giving it a second thought.

- Pasted Pieces of Paper

-

Interactive Notes Flipped Open

-

Pasted Hidden Side

-

Glue Marks

-

Glued Piece of Paper

Based on the fact that the book is produced in manuscript and not in print, it seems to suggest that Berendt intended for his book to not be replicated or for there to be only one original copy of his book. Given the fact that there are pasted slips on certain pages, different types of pages, and various binding methods for certain sets of pages, this book was conspicuously being crafted over a long period of time. The book looks to even be unfinished, as there are blank pages that contain page numbers. This book was set to function as a special collection of his work that related to and accompanied the receipts of Pío Pérez only for the purposes of research and for others to use it as a source for their research. Since he sold multiple manuscripts to Brinton, it is possible that money was involved. Perhaps he believed that there would be more value to the raw version of his important work in studying Mesoamerican linguistics than to reproduce it for the world.

Notes

- ↑ Pérez, Juan Pío, C. Hermann Berendt, and Daniel Garrison Brinton. Recetarios De Indios En Lengua Maya: Índices De Plantas Medicinales y De Enfermedades. Mérida, 1870.

- ↑ Paxton, Merideth. "Chilam Balam, Books of." In Davíd Carrasco (ed).The Oxford Encyclopedia of Mesoamerican Cultures. : Oxford University Press, 2001.

- ↑ Pérez, Juan Pío, Raquel Birman Furman, and C. Hermann Berendt. Recetarios De Indios En Lengua Maya: Índices De Plantas Medicinales y De Enfermedades. 1a ed. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones Filológicas, Centro de Estudios Mayas, 1996.

- ↑ Weeks, John M., Andree Suplee, Larissa M Kopytoff, and Kerry Moore. The Library of Daniel Garrison Brinton, 4-11. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 2002.

- ↑ Hoil Juan José, and Ralph L. Roys. Introduction. In The Book of Chilam Balam of Chumayel, 13. Washington D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1933.

- ↑ “Daniel Garrison Brinton Collection, 1868-1956”. n.d. Accessed May 4, 2022. http://dla.library.upenn.edu/dla/ead/ead.html?id=EAD_upenn_museum_PUMu1098.

- ↑ Weeks, John M., Andree Suplee, Larissa M Kopytoff, and Kerry Moore. The Library of Daniel Garrison Brinton, 12-17. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 2002.