John Wright Commonplace Book: A Unique Late 18th-Century Manuscript

Introduction

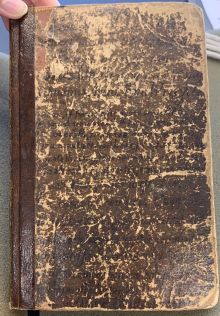

Opening the cracked leather binding of John Wright’s personal manuscript reveals a cursive, pencil inscription, “Book written by my great grandfather (maternal) Dr. Wright.” Created by the London physician from 1780 to 1800 and passed down for generations, this manuscript now resides in the University of Pennsylvania's Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, where it is catalogued as Ms. Codex 1638. The codex’s faded cover encases over one hundred pages filled with a miscellany of handwritten entries. From medical records to bible passages to merchant ledgers, not a square inch of yellowing paper goes unused in this unique example of a commonplace book. Analyzing the content and material features of Wright’s manuscript provides insight into the author’s values, day-to-day activities, and intended legacy. At the same time, the book also raises questions related to its organization, use, and preservation.

Genre and Historical Context

Commonplace Books and Their History

Commonplace books can be defined as collections, often handwritten, of textual excerpts, quotations, commentary, and other memories that have been compiled for future reference. [1] The genre does not have rigid boundaries, as the designation of commonplace book has been applied to works ranging from any manuscript containing miscellaneous information to printed reference books published for public use. [2] However, commonplace books are usually thought of as being centered around literary content, revealing interactions between the books’ creators and the texts they read. [2] The word “commonplacing” has also been used as a verb to describe recording and commenting on written work to enable further analysis and reflection in the future. [1]

The genre of commonplace books dates back to antiquity, although their content and use have evolved over time. The earliest roots of commonplace books can be traced to the compilation and summarization of Greek and Latin texts into more manageable collections by ancient scholars in Alexandria, Rome, and Caesaria. [3] Later, throughout the middle ages, bible passages and writings by church fathers were selected and organized into florilegia, such as Thomas of Ireland's Manipulus florum. [3] Motivated by scholars’ enthusiasm for discovering and managing information and enabled by the wider availability of paper, commonplace books increased in popularity during the Renaissance. [3] Eventually, commonplace books reached their golden age from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries, driven by information overload as well as a cultural emphasis on collecting and accumulating. [3] Although declines were seen in commonplacing with the advent of scrapbooking during the 19th century, these books remain important today in serving as windows into the experiences, thoughts, and memories of historical readers. [1]

The Georgian Era

John Wright’s commonplace book, written from 1780 to 1800, was created in the context of England’s Georgian period. Commonplace books of this era were characterized by flexibility and a lack of uniformity. [2] Some notable commonplace books were printed, such as Jeremiah Whitaker Newman’s The Lounger’s Commonplace Book, a collection of biographic, political, literary, and satirical anecdotes published in 1792. [2] Other examples were handwritten on pre-bound notebook paper or individual quires later stitched together, ranging in size from pocket to folio, [4] and often included sketches, caricatures, and illustrations in addition to textual extracts. [2] Toward the end of the 18th century, text clippings became popular additions to commonplace books due to the increased availability and affordability of print. [1] John Wright’s manuscript lacks many of these embellishments, as it includes only handwritten entries with no illustrations or text clippings.

Commonplace books during the Georgian era served a variety of purposes for the author and, in some cases, intended audience. Influenced by the Protestant emphasis of scriptural study and reflection, commonplace books allowed authors to remember and revisit passages, which otherwise may not have been possible due to the practice of compiling information from borrowed books during this time. [1] In addition to this practical purpose, commonplace books could serve to demonstrate an author’s prestige in being literate and well-read. [1] Commonplace books could also be written on behalf of others, such as parents imparting morals to their children, or children demonstrating their educational progress to parents. [2] John Wright’s commonplace book is an example of the former, as he includes numerous instructional maxims; commentary on values such as wit, honesty, and friendship; and letters directly addressed to his children, Euphemia and Charles. Moreover, commonplace books reflect the changing intentions of authors and were often repurposed for different functions midway through, [4] which is seen in the three distinct sections of Wright’s book.

Contents and Organization

Part 1: Medical Documentation

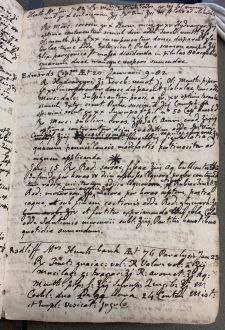

The first seven leaves of the book consist of records of Wright’s medical practice, including the date, name, and age of each patient. These entries are scrawled in Latin and utilize many abbreviations, suggesting they were intended for personal use rather than for others to read. In one entry, Wright utilizes an asterisk to continue a patient record on a subsequent page (Ms. Codex 1638, fol. 7r-v), indicating that he might have pre-allocated pages, writing out the dates and patient names and demarcating spaces with horizontal lines in advance of his visits to save time. Rather than organizing information by patient, Wright documents all of his interactions chronologically from May 16th, 1780, to July 8th, 1782, with one final entry much later on June 13th, 1795 (Ms. Codex 1638, fol. 8r). These records offer a glimpse into Wright’s daily life as a physician and his attention to detail in tracking each patient’s progress.

-

Medical entries of patient interactions in 1782

-

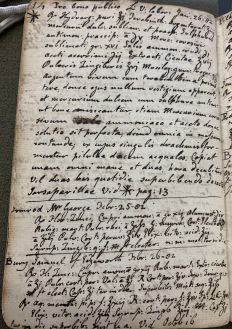

Continuation of a patient record using an asterisk

Part 2: Content for Wright's Children

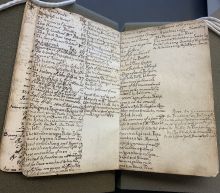

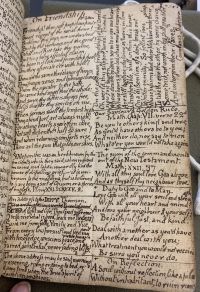

The second section of the commonplace book consists of fifty-three leaves of quotes, Bible passages, poetry, and personal commentary on important values for Wright's children, Euphemia and Charles. This section begins with a table of contents spanning two pages that contains titles and page numbers of several of the entries (Ms. Codex 1638, fol. 8v-9r). However, the page numbers are only included up to 49, after which the list items only have titles. As different lines on the table of contents appear to have slightly different spacing, pen thickness, and script size, it seems that information was added to the table of contents over time as entries were created, rather than the table of contents being planned and written in advance. Moreover, there does not appear to be an obvious alphabetical or thematic ordering of topics, as separate entries on politeness can be found on folios 32 r and 36 v, for example. Wright’s method of organization is notable as many commonplace books during this period followed a more rigid and planned structure. In the late 17th century, philosopher John Locke[ promoted a system of organization involving indexing entries by the first letter and subsequent vowel of their topic, and this method remained influential throughout the 18th century.[1] [4] Therefore, Wright’s comparatively free-form style of commonplacing may reflect his prioritization of content and flexibility over organization.

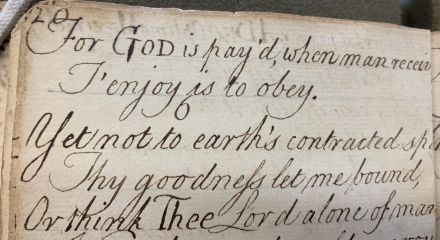

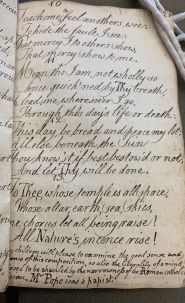

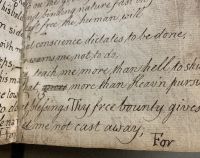

The entries in this section contain excerpts from prominent writers including William Cowper, Alexander Pope, James Beattie, and Anna Letitia Barbauld [5], which are often followed by footnotes detailing Wright’s reactions to the texts and instructions for their use by Euphemia and Charles. For example, Wright notes, “This poem is written with great delicacy of poetical sensibility. The reflections are natural and spontaneously lead us to moral and serious meditations, suitable to the minds of thinking men” after James Beattie’s “The Hermit” (Ms Codex 1638, fol. 12r). However, it is interesting to observe that certain entries also contain more humorous, lighthearted content. In one section, entitled “Enigma’s, epigrams, elegies,” Wright compiles several short poems that serve as engaging riddles for the reader to guess what the poem is describing. In another entry, Wright transcribes Jonathan Swift’s comical and outrageous poem “A MawWallup,” preceded by the comment, “This is execrably abominable, but it shows geniusly the humor of its author” (Ms Codex 1638, fol. 39v-40v). These passages offer a window into Wright’s relationship with his children and demonstrate an unexpected playful aspect of his parenting.

Furthermore, although most of the entries are undated, it is interesting to witness the progression of content as Wright’s children mature. Early entries appear to be directed toward school-age children, such as a copy of the poem “The Jackdaw” by William Cowper, followed by Wright’s observation, “Such little poems written with genius and vivacity often instruct young persons to read, to think and to pronounce well” (Ms Codex 1638, fol. 15r). However, Wright reflects on the growth and maturity of his children later in the book, with comments including “My lovely Euphemia is with a cultivated and admirable understanding…” (Ms Codex 1638, fol. 49r) and “My dear Charles W. Henry who is now an officer in the Russel-court volunteer association…” (Ms Codex 1638, fol. 50v). This progression creates an immersive narrative, allowing the reader to experience the children’s growth through their father’s eyes. Moreover, the maturation of Euphemia and Charles is mirrored by the author’s own aging, which is made manifest in his final entry of this portion of the book:

It is probable that this sententious mode of writing may have its use. If I have made any repetitions of the same sentiment [which I dare say I have] my children may impute it to the true cause, that a man full of days whose corporeal and mental faculties decline apace, cannot exactly remember in a medly of such subjects, what might have flowed from his pen, therefore he hopes this imperfection or rather true state of his situation, may be his best apology… (Ms. Codex 1638, fol. 61r)

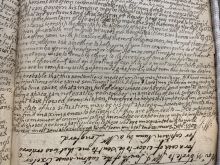

Part 3: Business Records

The last two leaves of the book, entitled “Letter book with the contents of letters sent on business with the dates and particulars” (Ms Codex 1638, fol. 62r), contain records related to Wright’s wine-importing business from 1792 to 1795. Wright takes meticulous notes on client correspondences, including quantities of wine, pricing, and dates of transactions, and even carries out calculations in the margins. Surprisingly, the first business record begins on the same page as the final entry to Wright’s children, a letter ending with the line, “May my most amiable children profit from my best endeavors,” which is signed and dated in September of 1800 (Ms. Codex 1638, fol. 61r). Approximately three-quarters of the way down the page, the orientation of writing is inverted, and Wright records having sent a bottle of sherry as a sample to a potential client in October of 1795 (Ms. Codex 1638, fol. 61r). This unexpected transition raises questions about why Wright would choose to reuse a page containing business records for the last entry of his commonplace book five years later, especially given the sentimental nature of his final letter.

Based on the dates of each segment of the book, it seems plausible that Wright began this manuscript as a medical notebook, pivoted and started writing from the back of the book after opening his wine business, and again changed focus to his legacy and children as he neared old age in the remaining intervening pages. It is also possible that Wright viewed this book as a general notebook to document all of his affairs throughout his life in one convenient place or was simply attempting to conserve paper. Regardless, the progression through the three distinct sections provides interesting insight into Wright’s changing ways of thinking and writing as his career and family evolved.

Material Analysis

Binding and Pages

The binding of the book is comprised of brown leather measuring 187 by 123 millimeters, [5] and the spine is wrapped in brown paper with no inscription. Text has been written on the front and back covers in black ink, but the leather is chipped and worn so that the text has become illegible. It is possible to distinguish a few words on the front cover, including “Wright” and “care,” suggesting this cover may include a description of the book’s contents or instructions for its use.

The book’s 62 leaves are composed of laid paper, as evidenced by the ridged texture. It appears that the pages have been cut down at some point after they were written, which is made manifest by writing going into the gutter as well as several page numbers in the top right corners being cut off. However, it seems that the book has not been rebound due to original writing on the cover and in the back pastedown, which contains a continuation of the content of the commonplace book and is filled with “Maxims on observations the result of experience.”

Manuscript Features and Layouts

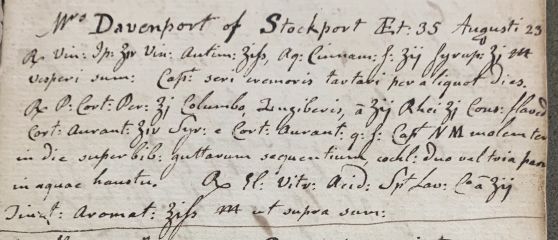

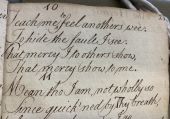

Wright makes use of different styles of handwriting depending on the content and function of each of his notes. While his medical records are written in small, often densely packed or smudged script, Wright starts to use a larger, more elegant hand as he begins the second section of the book. There is also evidence of pencil ruler markings in some of the entries soon after the table of contents (Ms. Codex 1638, fol. 11v-12r), which could have been used to ensure the writing was straight. These adjustments may represent a shift in the intended audience from Wright himself to his children.

-

Small, smudged writing in medical records portion of book

-

Larger, more legible handwriting with ruler markings in second portion of book

However, not all of the writing in the section dedicated to Wright’s children is large and easily legible: many pages contain Wright’s comments or reactions written in small script at the bottom of the page or vertically in the margins. Certain sections, such as “On Friendship” (Ms. Codex 1638, fol. 22r) and “Enigma’s, epigrams, elegies” (Ms. Codex 1638, fol. 23r-24v) even have quotations and poems written in different orientations such that the book would have to be rotated to read each item. Wright’s unconventional layouts suggest that he may have been trying to maximize the amount of page space and that he prioritized including all important content he came across for his children at the expense of aesthetics.

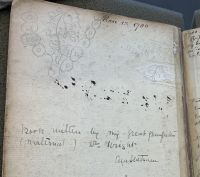

Readership and Provenance

Wright’s commonplace book contains several clues hinting at generations of readership. The book’s inner hinges at both the front and back covers have been reinforced through the use of tape, suggesting the book may have been opened and closed numerous times over the last two centuries. Furthermore, it appears that tape has also been added to folios 8 and 9 near the binding, resulting in some text being cut off in the gutter. As these two folios make up the table of contents, the presence of tape may suggest that these pages underwent the most wear and tear due to being turned to frequently in order to locate other entries. Additionally, although the pages lack marginalia, potentially due to the absence of available whitespace, the front endpaper contains pencil drawings of flowers and leaves which extend under the tape at the inner hinge, suggesting they were added by one of the book’s early readers.

The most definitive clue pointing to the book’s circulation is the inscription on the front endpaper, “Book written by my great grandfather (maternal) Dr. Wright.” Signed by Ann Statham, this note indicates that the book was passed down within the Wright family for at least three generations. Perhaps the book was used to educate Euphemia or Charles’s children, extending the influence and legacy of John Wright. Eventually, however, the manuscript was acquired by Justin Croft Antiquarian Books, a rare book trader in Faversham, England, and sold to Penn Libraries in 2012. [5] This trajectory raises questions about why the book left the Wright family after multiple generations and whether Ann Statham was the final owner. For now, Ms. Codex 1638 lies deep in the Kislak Center for Special Collections, waiting for the next reader to profit from Wright’s best endeavors.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Allan, David. “Remembering Reading The British Commonplace Book in the Long Eighteenth Century.” In Perceiving, Preserving, and Remembering: Commemorative Practices and Theories in the Visual Arts, 1650 to 1850, edited by Gockel, Bettina, and Miriam Volmert, 141–54. Berlin, Boston: DeGruyter, 2017.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 . Allan, David. “‘Many Sketches & Scraps of Sentiments’: What Is a Commonplace Book?” In Commonplace Books and Reading in Georgian England, 25–34. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Blair, Ann. “Note-Taking as Information Management.” In Too Much to Know: Managing Scholarly Information before the Modern Age, 62–116. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2011.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 James, Kathryn. “Notes and Bound Notebooks.” In English Paleography and Manuscript Culture, 1500-1800, 140–59. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2020.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 “Ms. Codex 1638 - Wright, John, M. D - [Commonplace Book].” Franklin. Penn Libraries. Accessed April 3, 2022. [1].