Jiu Huang Ben Cao: A Plant Atlas for Famine

Introduction

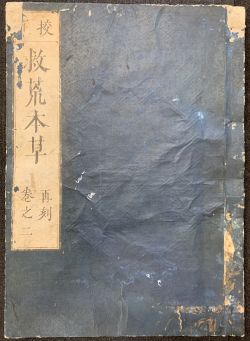

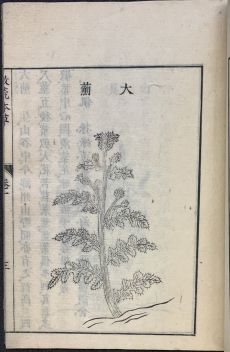

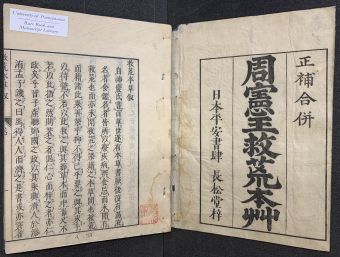

Jiu Huang Ben Cao ("Materia Medica for Famine Relief") was an illustrated botanical manual for plants that could be used for survival during famines, written by Zhu Su (朱橚) in the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). The book has multiple editions with this particular one likely being the first Japanese edition published around 1716 in Kyoto (京都) by Chōshōdō (長松堂). A total of 414 species of plants were recorded, each with exquisite woodcut illustrations. Among them, 245 kinds of grass, 80 kinds of wood, 20 kinds of grain, 23 kinds of fruits, and 46 kinds of vegetable were organized into different sections. The edible parts were further categorized into leaves, roots, fruits, and so on to facilitate identification. The author not only illustrated many of the collected plants, but also described the morphology, growing environment, and processing methods. The book was based on careful observations of collected plants and was considered to be of relatively high academic value by many botanists.

History

Prince Zhu Su(朱橚) was the fifth son of the Hongwu Emperor (1328–1398), who was the founder of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). He was a talented scholar with a keen interest in medicine. When he was banished to Yunnan in 1389, Zhu witnessed the difficult circumstances people were living in and learned that many of them were suffering from diseases and a lack of medicine. He realized the importance and urgency of compiling prescription books that would be useful for people during famines. Upon returning to Kaifeng, he started organizing a group of scholars, gathering skilled painters, and collecting a large number of books. He also set up a botanical garden to grow various plants that were known from surveys to be edible to conduct observation experiments. Although he was banished to Yunnan once once in 1399, he never stopped his research on prescriptions and plants for famine. In 1406, the book Jiu Huang Ben Cao was published. It was later printed in thousands by the government and gratuitously distributed to districts that frequently suffered from natural calamities.[1]

There were a number of editions that emerged beginning in the sixteenth century. The second edition was ordered by Bi Mengzhai, the governor of Shanxi, in 1525. The third edition was printed in 4 volumes in 1555 with woodblocks engraved by Lu Dong. Unfortunately, it mistakenly identified Zhu Su's son, Zhou Xianwang (周憲王), as the author. This error later appeared again in works such as Li Shizhen's Bencao gangmu (本草綱目) and Xu Guangqi's Nongzheng quanshu (農政全書). A few more editions were printed in 1562 by Hu Cheng and in 1586 by Zhu Kun. In 1639, it was reprinted with 413 plants as part of the Xu Guangqi's Nongzheng quanshu (農政全書) published by Hu Wenhuan (胡文焕). Jiu Huang Ben Cao was first published in Japan in 1716, with various manuscript copies also produced. The Jiu Huang Ben Cao was highly regarded in Japan during the Edo period (1603-1867) with many research conducted. The book was translated into English by the British pharmacist Bernard Emms Read, who also performed compositional analysis and claimed that the original woodcut of the Jiu Huang Ben Cao was superior to that of the Bencao gangmu.[2] The American botanist Howard S. Reed, in his book A Short History of the Plant Sciences, also praised the accuracy of the illustrations.[3]

Woodblock Printing

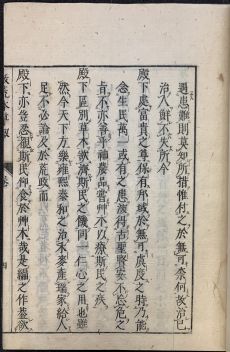

The text was printed in relief with both Chinese characters and small Japanese katakana characters interspersed closely nearby to provide reading aids for Japanese readers. The text is read top to down and right to left – in accordance with the ancient Chinese writing system. It is an example of woodblock printing, where the characters for an entire sheet were carved into a woodblock by a skilled carver. Each sheet was first printed with black ink and then folded in the middle. The used woodblocks were stored to be used in the future to create the same printing if additional copies were requested.[4] Woodblock printing replaced movable type due to its financial advantages and became the dominant way of printing in Japan during the Edo period, which was marked by a rapid growth of literacy and book sale.[4] Different parts like the title and listings were printed in different fonts and sizes with an appearance of handwriting, demonstrating the level of sophistication in printing in striving for more aesthetic and natural characters. The illustrations of different plants were exquisite and highly detailed, demonstrating the level of skill in the carving and printing processes in Japan at the time.[5]

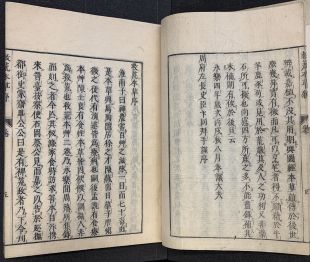

The papers feel soft and thin with a slightly yellow color. Under light, the sheets are almost transparent. Based on the time and location of its production, as well as the texture, the papers were likely made from rice. Each sheet of paper was folded in half to be bound using some strings on the other side, resulting in only a half of each sheet available for printing. Even with the folding, printed texts from the other side can be seen due to the semi-transparent nature of the substrate, which creates a filmy texture that captures the feeling of “朦胧” (meng long) with beautiful texts gently appearing from behind – an aesthetic valued in many Eastern cultures.[6] The thin and semi-transparent substrate not only had the advantage of being cheaply produced, but also allowed many pages to be bound even with the folded sheets without drastically increasing the thickness of the book. It also allowed the book to be lightweight and soft. Due to the softness with similarly soft paper covers, the book was likely to be laid flatly for storage. The inked writing of the title and volume on the bottom-edge of the books also suggests that they were likely stored flat with the bottom-edge out for identification. The soft and thin nature of the sheets also made it prone to damages like tearing. The need for careful handling of delicate books reflects Confucius values in patience and high esteem for books by many Eastern cultures. Because increasing the number of sheets made it easier for tearing to happen, the book was assembled into eight separate volumes. The blocks of text were printed consistently on the lower end of each sheet with larger margins on top. This was a practice consistent with the Chinese “書眉” (shumei, meaning “book eyebrow”) or “天頭” (tiantou, meaning “heavenly head”), which was used for annotations.[7]

Fukurotoji Binding

The platform of the book is a wrapped back binding codex with text chiefly in 9 vertical lines. This type of binding was first developed in the thirteenth century in China, later spread to Japan and became a traditional Japanese binding known as fukurotoji (or bound pocket books), and was used through the seventeenth century.[8] It is very different from the western form of codex. Each sheet was block-printed only on one side and was then folded in half with text outward, resulting in text on both sides. The assemblage of individual folded sheets using strings after woodcut printing of entire sheets allowed easier production of accordions. This type of binding was an advancement from the earlier butterfly binding, which had creases of individual folded sheets glued to result in two blank pages between each pair of printed pages. The development of wrapped back binding helped create an uninterrupted reading experience.[4]

Besides the folded-folio technique of wrapped back binding, the accordion uses a thread-based system, which involves a sewn binding.[9] Holes were drilled into the open edges of the stack of sheets for strings to thread through. The spines were left unwrapped by paper covers, exposing the open edges of sheets and strings. This was an advancement from earlier glued covers, which often attracted bugs. With strings, the accordion can be easily taken apart for repairing without damage to sheets. However, because of the soft and thin sheets, with repeated usage, the binding strings can fall out. This loss of binding with loose sheets can be seen in volume three and four, showing extensive usage of the book in the past.

On the front cover and the pastedown of the books, information about the title, edition, and volume is indicated on the left hand side from top to bottom. In the middle of each sheet, a narrow vertical column consisting the title and chapter number of the book was printed. Because each sheet was folded, a half of the column is visible on each page. With the ability to quickly flip through different pages afforded by codex, readers can identify specific sections of the book with ease. In addition, because the appearance of each number is different, unique traces of each character can be seen on the fore-edge (which is composed of the folded area of sheets known as “the Pillar”), allowing experienced readers to use it as an additional navigational tool. For each section, a title was included prior to text in the rightmost column and positioned higher than most of the following text for easier identification and navigation. An ending phrase including the title of the book or the title of the section can be found at the end of every section in the leftmost column.

Innovations

Jiu Huang Ben Cao was innovative in that nearly two-thirds of the plants were not previously recorded. Unlike traditional materia medica works, Zhu's descriptions were characterized by its simple and common language and based on direct observation.[10] The illustrations in the book were more accurate and realistic than previous ones. As a result, the book was of great significance both in terms of developing the field of botany and facilitating people's search for food.[11]

In addition to purely edible plants, the book also included plants that contained some degree of toxicity. Based on the claim in many classical herbal books that beans can detoxify, Zhu came up with the preparation method of steaming the poisonous Indian pokeweed together with bean leaves to eliminate its toxicity. It is noteworthy that the book proposed to remove the toxicity of poisonous celandine by cooking it with "clean dirt", a method that is theoretically consistent with the chromatographic adsorption and separation invented by the Russian botanist Tsvet in 1906.

Significance

Successive dynasties of ancient China were often associated with heavy taxation, frequent warfares, and disasters. It was a common practice to use chaff, grass roots, and bark as food for survival.[12] An abundance of empirical knowledge about consuming wild plants was accumulated and in urgent need of compiling into written text and improvement. Jiu Huang Ben Cao was significant not only in alleviating the lack of food during famines, but also in pioneering the study of wild edible plants. This book, along with many others such as the Xiuzhen fang (袖珍方) and the Puji fang (普濟方), has contributed a lot to the development of agriculture and medicine, with influence seen in many later works such as Bencao gangmu (本草綱目) and Nongzheng quanshu (農政全書). An emphasis on agriculture and edible plants was fundamental to the stability of successive political establishments in China and the persistence of the oldest surviving continuous civilization in the world with a history of more than four thousand years, contributing not only to the development of a variety of cuisine, but also a population of at least 160 million, which was remarkably close to 40 percent of the world population, at the time.[13]

Jiu Huang Ben Cao evoked great interest among Japanese scholars at the time and appeared in a number of similar works. Furthermore, the method of planting plants in botanical gardens for observation and recording had a profound influence on the development of Japanese botany. In the 1930s, the American scholar W.T. Swingle considered Jiu Huang Ben Cao to be the world's earliest known and still the best monograph on the study of edible plants for famine relief.[14] He also believed that it contributed to the development of the large number of cultivated plants in China today, which was probably ten times as many as that in Europe and twenty times as many as that in the United States. The American botanist H.S. Reed, in A Short History of the Plant Sciences noted that Zhu's book was an outstanding work of early Chinese botany and an important source of knowledge in the history of plant domestication in the East.[3]

The Japanese edition of Jiu Huang Ben Cao is also one of many examples of a reflection of the hierarchical society of Japan at the time. Belonging to the category of refined literature, which encompassed Japanese and Chinese classics and medical texts, the book was primarily circulated among the social elites and scholars of the Edo period.[4] It reflects the significance of printing to the development of science and medicine in promoting the spread of knowledge.

References

- ↑ Needham, Joseph; Lu, Gwei-djen; Huang, Hsing-Tsung (1986). Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 6 Biology and Biological Technology, Part 1: Botany. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521087315.

- ↑ Read, B. E, & Li, S. (1931). Chinese materia medica ... Beiping: Peking Natural History Bulletin.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Reed, H. S. (1942). A short history of the plant sciences. Waltham, Mass.: Chronica botanica company.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Hioki. (2009). Japanese printed books of the Edo period (1603–1867): history and characteristics of block-printed books. Journal of the Institute of Conservation., 32(1), 79–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/19455220802630768

- ↑ Kornicki. (2001). The book in Japan : a cultural history from the beginnings to the nineteenth century. University of Hawai'i Press.

- ↑ Sikong, T. (n545). Sikong Shi pin. Taibei: Yi wen yin shu guan.

- ↑ Bretelle-Establet. (2022). Biography of the Medical Book in Late Imperial China. A View from the Southern Margins of the Qing Empire. East Asian Science, Technology, and Medicine., 54.

- ↑ Anne Burkus-Chasson. (2005). Visual Hermeneutics and the Act of Turning the Leaf. In Printing and book culture in late Imperial China. University of California Press,. https://doi.org/10.1525/j.ctt1ppz91.15

- ↑ Edgren. (2019). China. In a companion to the history of the book. Wiley Blackwell,. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119018193.ch16

- ↑ Brokaw. (2016). The history of the book in East Asia. Routledge.

- ↑ Read, B. E. (1946). Famine foods listed in the Chiu huang pen ts'ao : giving their identity, nutritional values and notes on their preparation. Published by the aid of a grant from the British Council. [Shanghai]: [Henry Lister Institute of Medical Research].

- ↑ Sarah, H. C. Fulfilling the Potential of All Plants: "Jiuhuang Bencao" and the Discourses on Famine Foods in the Ming Dynasty. Ming Qing Studies 2021, 87.

- ↑ Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1999), The Cambridge Illustrated History of China, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-66991-7.

- ↑ Swingle, Walter T. (1935). "Noteworthy Chinese Works on Wild and Cultivated Food Plants". Report of the Librarian of Congress for the year 1935. Library of Congress. pp. 193–206.