Edith Mary Mellor's Travel Diary

Introduction

Diaries have emerged as an indispensable source for historians, offering a glimpse into the cultural and social environment of the past through the eyes of the author. As personal diaries were typically kept to remain private or have limited circulation, the thoughts, emotions, and experiences divulged within diaries can be some of the most intimate and unfiltered windows into history. This allows researchers to not only begin to understand public opinion on current events or day-to-day lifestyle and habits, but grasp history from a more human perspective, digesting personal accounts written in thorough detail. As such books are rarely ever published or promoted publicly, when one is found in library special collections, questions emerge regarding the authorship, how the item circulated into public eye, and how the book was personalized to tell a unique story.

One example of such a special book includes the Edith Mary Mellor Travel Diary, which can be found in the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts at the University of Pennsylvania. Penn Libraries purchased this diary from Eclectibles in 2015 from Tolland, Connecticut.

It remains unclear how the book made its way from England to Connecticut, but it could be speculated that the book remained in the family’s following generations’ hands, who could have then moved to the United States many decades later. Edith Mary Mellor is known to have been born in Windsor, Berkshire, England to Elizabeth Mary Widcombe, her mother, and Albert Mellor, her father and a musician who worked at Eaton College. Her family also consisted of her two sisters, Doris Evelyn and Berta Clara Rosalind. Mellor studied at Oxford and received a Master of Arts in 1912, and went on to teach and transcribe books into Braille for the National Library for the Blind.[1] This diary follows the travels of Mellor as she journeyed from England to Jerusalem and Egypt, embarking on her voyage on November 30, 1934 through January 17, 1935.

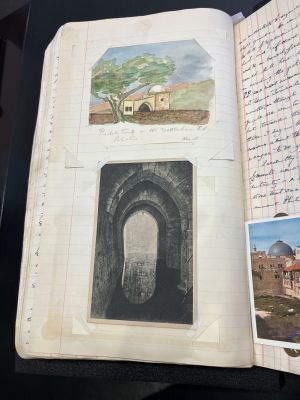

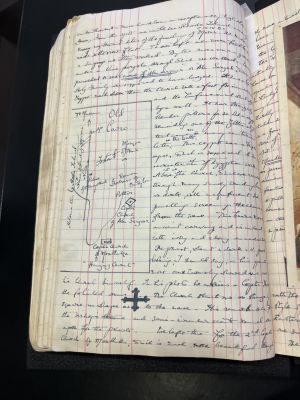

The book features an eclectic collection of items within the bounded pages, gathered from stops throughout her travels. Postcards, photographs, and guidebooks could be found tucked between the pages, complemented with pressed plants, hand drawn maps, and an unsent letter from Mellor addressed to her sister, Doris. Amongst these artifacts of Mellor’s adventures, her writing flowed across the pages and surrounded the attached objects, detailing not only her raw observations, but also her reflections on her experiences with the people and places of the various cultures she interacted with. At times, these writings brought light her personal feelings and beliefs, becoming more introspective writing. In addition to such accounts, she provided informative content, explaining the historical significance of the various major landmarks and sites she had visited.[1] With such a diverse array of content at a reader’s disposal, there is much material to analyze, paving way for analysis on Mellor’s personal life and how her journey and perspectives intertwine with the context of the time and place, revealing not only valuable historical information, but also the significance of this genre of book to society.

History of Genre

The term “diary” is defined by Merriam-Webster as “a record of events, transactions, or observations kept daily or at frequent intervals, especially a daily record of personal activities, reflections, or feelings.”[2] It is argued that the diary form emerged in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries as a response to the development of the concept of “incremental time.” Rather than viewing time as “elastic,” time was viewed as a “relentless continuity.”[3] The diary then became mass-marketed in the beginning of the twentieth century as major diary manufacturers competed intensely with each other. They fought to design the most desirable products, introducing diaries with exotic leather covers, specialist diaries, and preliminary pages full of random informative facts. Thus, diaries began to develop particular textual and visual conventions attributable to the genre.[3]

The popularity of diaries only continued growing as Mass Observation, a social research organization, pushed consumers in the late 1930s towards the value and significance of diary keeping. This campaign for day surveys was motivated by the desire for greater democracy and egalitarianism, hoping to better educate politicians on the lives of ordinary citizens for better governance.[3] Nonetheless, the popularity of diaries was also supported by the development of World War I, as a sharp rise in diary keeping ensued, possibly attributable to the psychological benefits of offering a space for individuals to reflect and unload their traumas, fears, and frustrations onto paper in relation to the war.[3]

The twentieth century also experienced a spur of travel writing. With two world wars, the trend of globalization, and technological advances, mass tourism commenced. Modes of transportation developed, such as through the motorcycle, car, and air travel, allowing individuals to reach new areas more easily, specifically the countryside. Since motor vehicles were praised as means of getting closer with nature, instead of tainting it, such explorations were further encouraged.[4] Furthermore, Britain’s shifting relationship with its colonies also sparked literary travel writers, as many authors saw travel as a journey to gain clarity on identity and culture. As doubt on Britain’s superiority began surfacing, many sought out travel as an escape to find more positive substitutes abroad.[4]

Overall, between the 1920s and 1950s, diary keeping helped further the notion of self, privacy, and value of ordinary life. Meanwhile, travel writing in Europe, especially during this period, promoted reflection on the construction of boundaries by both the travelers themselves and by the wider world.[5]

Material Analysis

At first glance of the book, one detail stands out the most amongst the cardboard cover wrapped in red leatherette: “Petty Cash” written in black text.

Whilst the rare item was a travel diary, Mellor wrote her compositions in what was clearly a repurposed ledger book, intended for accounting and finances. This was a peculiar choice, as the ledger book format entailed vertical red lines running across the pages, even though Mellor’s words were written horizontally on light blue lines. Furthermore, as previously mentioned, diaries were mass-marketed at the time, featuring distinct conventions designed for the genre, leading to questions as to why Mellor chose to not write her travel diary in a traditional diary book. Nonetheless, Mellor employed her own conventions to turn the ledger book into a travel diary. For example, the endpaper on the inside of each cover was the same ledger book page design. However, inside the back cover, an old envelope had been attached on top of the endpaper, where Mellor could have conveniently stored materials that she later included in the travel diary, such as postcards, photographs, or letters.

Additionally, the binding structure of the book implied heavy use and wear. As bookbinding automation expanded in the twentieth century, sewn book blocks with an adhesive applied for backing material on the spine was common for the time. Observing the loose threads coming out from the poor state of the binding, and the significant separation between the book block and headbands, and between the covers and the book block, one could presume a similar technique was used for the book’s construction. Furthermore, taking note of the darkened edges of the pages near the center also indicates frequent use, as the constant contact of fingers to these areas of the pages would result in greater wear and heavier dirt allocation.

Content

In analyzing the content of the book, it is critical to first examine how the book is organized. On Page 1R, the book includes a page functioning as a title page, captioned with “Palestine and Egypt. November 30th, 1934 – January 17th, 1935. Via P. & O. & Orient Lines of Steamships, Port Said & El Cantara.” Detailing not only the dates and locations of the trip, but also the mode of transportation, this page offers a sufficient overview of the contents of this travel diary. Moving on to page 2V, an itinerary of the trip is included, offering further detail as to how the content will be organized chronologically. However, this is the extent to which navigation is employed within the book. Throughout the pages, there are no headings to separate the body of text explicitly by dates. This observation offers insight into how the author likely intended readership. Rather than skipping around from section to section to indulge in certain portions of the trip, the reader would be forced to read the travel diary straight through from beginning to end to best comprehend the recounted stories. The lack of dating with each entry is unusual for a diary, as this transgresses one of the essential elements of the genre. Lacking such dating, some historians may argue this book to transform more into a notebook rather than a diary.[6]

However, even without headings for navigation, Mellor did employ the asemic writing marks of underlining, which may have been used to emphasize certain details of her travel narrative. Oftentimes, Mellor underlined the names of locations with two lines under the words. This may help the reader more easily identify when Mellor has reached a new travel stop. Thus, even without headings or dates, a reader could still roughly skim over the content and pick out important words or phrases that were underlined, allowing for quick identification of key locations.

Mellor’s travel diary also includes numerous examples of marginalia, filling the edges of the pages as the text surrounds photographs, postcards, and pressed plants.

In such instances, the marginalia contributed more to the content of the travel diary by offering insight on the materials attached to the page. In other instances, the marginalia contributed to the grammar and sentence structure, or added small clarifying details to the story being told in the main body of text. Such examples were typically denoted through a “^” symbol with the corresponding notes written within the main body of text’s lines, or through an “x” in a circle with the corresponding annotations nearby in the margins. It is important to point out how the marginalia was sometimes written in a blue ink, contrasting the black ink that was used to write the entirety of the main body of text. This change in ink color strongly suggests that the marginalia was added at a separate, later moment than when the main body of text was written. It could have been a result of Mellor remembering details later, and deciding to add them in.

At times, the marginalia also seemed to have been written in a different handwriting than Mellor’s, pointing to an unknown secondary author contributing to these annotations. These could have been from her travel companion, Mrs. Matthew, since this individual would have also had shared experiences to contribute to the travel diary. It is possible that Mrs. Matthew had her own thoughts to share, or remembered certain details Mellor forgot, and in turn, she wrote in marginalia. On the other hand, these samples of marginalia very well could have still been written by Mellor, but merely appear to be of a different handwriting because a different writing utensil was used, which could impact handwriting. When individuals utilize different writing tools, their way of holding the tool may change, which may impact and distort one’s normal handwriting.[7]

Another standout characteristic of Mellor’s travel diary is the vast variety of pressed natural objects, consisting of mainly flowers and plants, with even one set of bird feathers. Pressing plants has a rich history of practices, but “Collecting and Preserving All Kinds of Natural Curiosities” of 1776 details the most common technique for drying plants that traces back centuries, still standard even today. The technique involves collecting the specimens on a dry day, and then preserving them between sheets of paper with a weight to press them flat. Once dry, it was recommended to spread a coat of gum-arabic and then copal varnish to protect the specimens.[8] Analyzing Mellor’s travel diary, dried marks of a brown substance can be found outlining the pressed plants, suggesting that Mellor used an adhesive substance to stick the specimens to the pages of the book. However, the pressed plants felt uncoated by any protective coat. Most of the specimens also seemed to have lost most of its color, mostly resulting in shades of brown and oranges, a common challenge faced by botanists who would ideally like to preserve flowers' or plants' distinct colors.[8] On certain pages, one can also identify the mirror “reflection” of the plants on the page pressed against it, typically a brown color either resulting from the moisture of the plant or the adhesive used to attach it. This suggests that Mellor did indeed press these plants within her travel diary, rather than pressing it in other materials and then transporting the dried, pressed specimen into her book.

Moreover, Mellor exhibited an extensive use of photographs and postcards within her travel diary. Most of these objects were attached to the travel diary through adhesive photo corners pasted onto the pages. This proved an effective method for preserving and displaying the materials, as most remained intact inside the book. However, there was one standout page in the middle of the travel diary. This page was composed of a paper different from the typical ledger book format, but instead, resembled typical notebook paper with only horizontal lines, and was a smaller size to the rest of the pages. This page seemed to have been either a loose sheet of paper or torn from another book, and attached into the gutter between the recto and the verso with an adhesive. This technique is commonly called “tipping in” pages. This page also employed a different technique to attach three watercolor paintings and one postcard. The watercolor paintings were attached through diagonal slits that were cut directly into the paper, while the postcard was attached with small strips of adhesive tape placed over each of the four corners. It is unclear why Mellor opted a different technique for attaching these materials.

Significance

There remains a great unsolved mystery: Why did Mellor create her travel diary in a repurposed ledger book? The ledger book is a relatively large size and heavy weight, hindering the platform’s portability, especially when the author is constantly on the move while traveling. This hints towards a consideration that Mellor may not have been recording her experiences while traveling, but instead, waited to assemble the book at the conclusion of her travels. This supposition could be further supported by the fact that none of her entries included date. Instead, the content was written completely continuously with no distinct separation of time, as if she wrote it all in one sitting. Moreover, the main content of the diary was written in one ink and one pen, suggesting a consistency of writing that would be most supported if she had assembled the book upon the conclusion of her trip. The significant amount of marginalia, written in different color ink, pens, and even handwriting, also suggests that she may have been writing in the retrospective, as she adds in information as she recalls it. Nonetheless, this hypothesis begs the question as to how Mellor was then able to recount her experiences in such detail if she had to recall them by distant memory. The maps, drawings, and existence of pressed plants and feathers amongst the pages strongly suggests that Mellor had to have been writing in the moment to be able to preserve such memory and materials.

Placing Mellor’s travel diary in a greater context, this book also embodies the blurry lines between genres, specifically the diary versus the scrapbook. Since Mellor confides in her personal reflections, thoughts, and feelings of her travels, one may be inclined to consider it a diary, especially as the University of Pennsylvania Library titles the object as a “travel diary.”

In a simplified form, literary creators also typically recognize diaries as recording daily events, which Mellor does.[6] On the other hand, according to Ellen Gruber Garvey, scrapbooks in nineteenth century England referred to “portfolios of drawings, or collections of prints or silhouettes, and books which could circulate among friends or in which visitors to a household inscribed a few lines or a verse of drawing.”[9] Mellor combined such a wide variety of media, including drawings, paintings, and photographs, within her book, that the item teetered the classifications of a standard scrapbook. Going beyond a typical diary with just text, Mellor cut and paste a diverse array of content into her book.

There may never be a definitive answer as to what Mellor’s book should truly be classified as, whether a travel diary or scrapbook. Regardless, the artifact embodies the true significance of such books as it contributes to historians’ understanding of the time period and region. Mellor’s writing highlights the perspective of an England citizen, especially when exposed to different cultures of different regions around the world, providing context into social structures of the time and a more human view of history. Her account also opens a window into how travel was conducted in the twentieth century, such as modes of travel and places to stay, offering factual historical information. The pressed plants contribute to natural history even, classifying which species of plants could be found in which locations, which could then go on to offer insight of climate and ecosystem conditions of the time. Edith Mary Mellor’s Travel Diary provides an invaluable window into the past, permitting readers for decades to come, as long as the preservation of the book allows it, to indulge in what it felt like to travel internationally as an English woman in the 1930s, an experience that cannot be replicated without such a special artifact.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Penn Libraries, "Edith Mary Mellor travel diary, 1934-1935."https://franklin.library.upenn.edu/catalog/FRANKLIN_9964398483503681.

- ↑ "Diary," Merriam-Webster.com. Merriam-Webster, 2023.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Moran, Joe. "Private Lives, Public Histories: The Diary in Twentieth-Century Britain."Journal of British Studies,vol. 54, no. 1, 2015 January. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24701728?seq=1

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Das, Nandini & Tim Youngs. “The Cambridge History of Travel Writing: Travel Writing by Period.” Cambridge University Press, 11 January 2019, pp. 17-140. https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/D258E561CF58A7B1C3250F9F177EBA51/9781107148185c8_125-140.pdf/travel_writing_after_1900.pdf.

- ↑ Das, Nandini & Tim Youngs. “The Cambridge History of Travel Writing: Travel Writing in a Global Context.” Cambridge University Press, 11 January 2019, pp. 141-298. https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/A562138D44B24EF3EFBD4BDD2371A00A/9781107148185c12_191-205.pdf/travel_writing_from_eastern_europe.pdf

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Zboray, Ronald J., & Mary Saracino Zboray. “Is It a Diary, Commonplace Book, Scrapbook, or Whatchamacallit? Six Years of Exploration in New England’s Manuscript Archives.” Libraries & the Cultural Record, vol. 44, no. 1, 2009, pp. 101–23. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25549539.

- ↑ Gaydamakina, D. & Drobisheva, E. "About the Influence on the Signs of Handwriting Unusual Way of Holding the Writing Tool." Theory and Practice of Forensic Science and Criminalistics, Vol. 19, No. 1, 2019, pp. 226-238, https://doi.org/10.32353/khrife.1.2019.17.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Prince, Sue Ann, et al. “Stuffing Birds, Pressing Plants, Shaping Knowledge: Natural History in North America, 1730-1860.” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 93, no. 4, 2003, pp. i–113. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/20020347.

- ↑ Garvey, Ellen. "Writing with Scissors: American Scrapbooks from the Civil War to the Harlem Renaissance" Oxford Academic, 2012 November, https://doi-org.proxy.library.upenn.edu/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195390346.003.0001.