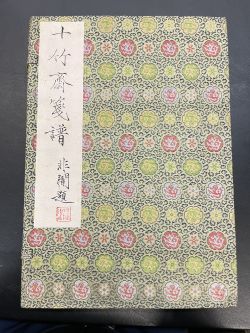

Chinese Poetry Paper by the Master of the Ten Bamboo Hall

Introduction

Chinese Poetry Paper by the Master of the Ten Bamboo Hall ("Ten Bamboo Hall Poetry Paper") is a collection of paintings first published by Zhengyan Hu in 1644 in China. In 1952, using the same printing technique as in the first publication, Beijing "Rongbao Zhai" reprinted the book and issued a limited reprint edition of 300 copies. The book has 4 volumes with 16 chapters, each focusing on one category such as birds, insects, animals, flowers, utensils, plants, stones, mountains, people, scenery, etc. The substrate is Chinese Xuan paper, a kind of thin paper fits perfectly with Chinese painting and calligraphy. The book is thread-bound as many old Chinese books are. It is not only the ancient poetry paper book with the largest number of patterns and designs, but also a treasure work combining painting, engraving and printing techniques of the Ming dynasty.

-

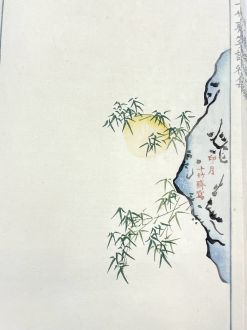

moon

-

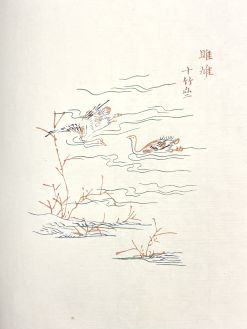

fish hawk

-

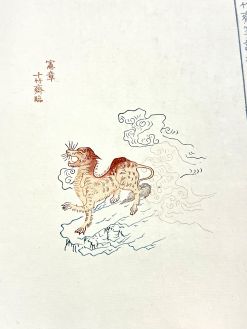

son of the dragon

-

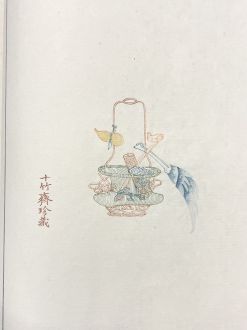

basket

-

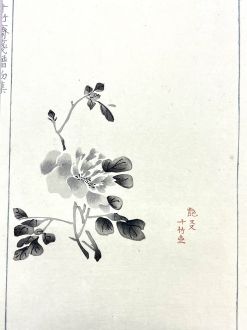

flower

Woodblock Water Printing

The special printing technique adopted by this book is called the woodblock water printing. The book marked the pinnacle of this special technique which represented the highest level of color overprinting technology in ancient times. Color printing in China began during the Song and Yuan dynasties. Color overprinting reached a flourishing period during the Wanli period of the Ming Dynasty, with the emergence color printing pictures. To the end of the Ming Dynasty, the woodblock water printing emerged. It is based on color overprinting and developed from the special multi-color overprinting method in Huizhou city during the Wanli period. The objects in the printed works have the shades of color and ink, and the printed paintings are almost identical to the originals. The woodblock water printing process is divided into three processes: sketching, engraving and printing. First of all, sub-pages are designed according to the original work. The original work is traced on transparent polyester or celluloid sheets, and the outline of the ink lines is traced precisely on goose skin paper. Then the craftsman reversely pastes it on the planed pear wood board or other detailed grain wood board, and uses different knives and knife techniques to carve out the line plate, brush plate or flat plate. Finally, the craftsman selects the materials and pigments used in the original work, dusts the ink and color onto the carved board, and then overprints onto Xuan paper, Lian Shi paper or silk as needed.

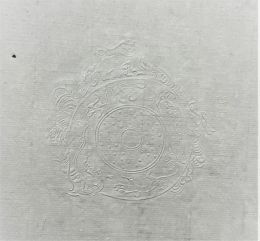

"Gong Hua" is a special part of woodblock water printing, a kind of engraved printing method without inking. Similar to the modern printing technology of embossing, the two carved concave and convex plates are nested together and arched on the Xuan paper, so that the page can be engraved with various types of light-colored or white ornaments. It uses the protruding lines of the ornaments to show the charm of the painted flowers, birds, fish, insects, artifacts and treasures. [1] "Gong Hua" is also observed in many patterns in this book.

The "Ten Bamboo Hall" which appeared in the name of this book is where the woodblock water printing technique was invented and developed. In 1952, when Beijing "Rongbao Zhai" reprinted the book, it invited the skilled craftsmen from Nanjing Ten Bamboo Hall as the technical force. In order to revive the ancient skills, Ten Bamboo Hall later sent craftsmen to Beijing "Rongbao Zhai" to learn woodblock water printing from a few masters in 1988 and 1989.[1]

Now, the woodblock water printing technique has been certified as an Intangible Cultural Heritage.

History

Zhengyan Hu, the author of the "Ten bamboo Hall Poetry Paper", was born in a doctor family in 1584. When he was young, Hu practiced medicine with his father, but he eventually abandoned his role as a doctor in favor of his beloved career in arts.[2] He lived a reclusive life in the Ten Bamboo Hall while concentrating on his artistic work. The production of painted "Ten bamboo Hall Poetry Paper" began in 1619 and was completed between autumn and winter of 1627. After that, he produced the printed "Ten bamboo Hall Poetry Paper" and completed it in 1644.[3]

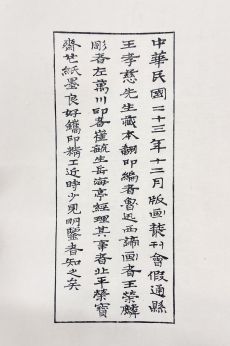

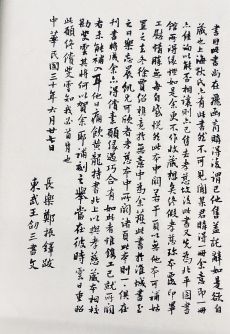

The reprint version that came out in 1952 should be attributed to two male activists and writers at that time: Xun Lu and Zhenduo Zheng. Lu once commented that the "Ten Bamboo Hall Poetry Paper" is "the highest achievement of the plaything for the literatisince the Ming and Qing dynasties." In 1934, he wrote a letter to Zheng, saying that the "Ten Bamboo Hall Poetry Paper" samples of flowers are the most exquisite, and this artistic approach exceeds many modern masterpieces; the landscapes inside are also very well engraved. " Then in April of the following year, Lu said to Zheng: "Such good set of books in the Qing Dynasty has been rare. Even in the future, I am afraid that there may not be such engraving and printing skills. Maybe in the next three hundred years, there will be no better than it." Zheng proposed to reprint the "Ten Bamboo Hall Poetry Paper" and asked for Lu's opinion. Lu also expressed a great interest in this project, and the motion was finally implemented. However, reprinting the book was very difficult, as the original copy published in 1644 was hard to find for Zheng. Eventually, Zheng borrowed a copy from Xiaoci Wang in Beiping and asked "Rongbao Zhai" to try out the reprint. He sent two samples of the reprint work to Lu. These two celebrities, one in Shanghai, one in Beiping, frequently disscussed the paper and pigments, layout, pricing, publication time and other issues via letters. Lu also wrote the reprint description for the book, printed on the flyleaf of the book. In 1935, the first volume of the book was published. However, Lu died of a disease on Oct. 19th, 1936, with the pity of not being able to see the whole book published. The whole book's reprint was completed in 1941. On June 27th, 1941, Zheng wrote the postscript for the book, expressing his regret and remembrance of Lu. In 1953, Zhenduo Zheng presided over another reprint when he was the Vice Minister of Culture. This time, he wrote another "Preface to the reprint of the Ten Bamboo Hall Poetry Paper".[4] The edition collected by Kislak center is th 1952 reprint version.

Poetry Paper

The whole book is about a very special item in Chinese culture: poetry paper. Generally, paper of larger length is referred to as "Zhi" (paper), while paper of fine production and smaller size is called "Jian" (poetry paper). Poetry paper refers exclusively to the Xuan paper printed with fine and light ornaments by traditional engraved printing method. It serves as a paper for literati to copy poems or write letters. Although the size of the paper is small, it combines poetry, calligraphy, painting and printing as a whole. It was a popular choice among the literati because of the visual beauty it brings to them. The Ming Dynasty was a period when poetry paper was flourishing and innovative. However, in the early years of the Ming Dynasty, the paper was mainly full-width, not carved, expensive paper. These papers focus only on practicality, and there was still a certain distance from the real sense of poetry paper. It was after the mid-Ming dynasty that the poetry paper experienced a qualitative leap forward. After 1601, with the fast development of woodblock water printing, poetry paper became more delicate and popular. Poetry paper made through woodblock water printing usually had flowers, birds, animals, landscape figures, and even astronomical signs and costumes on it.[2] It can be said that the paper and woodblock water printing are complementary to each other. One interesting thing on poetry paper is that through it, we can see how printing transformed traditional Chinese painting from an art form itself to a tool serving another art form which is closer to daily life. The "Ten bamboo Hall Poetry Paper", well-made, exquisite and probably designed only for collection, marked a trend of poetry paper's characteristic from being practical to ornamental.

Cultural Implications

There are in total 283 patterns in the "Ten bamboo Hall Poetry Paper". Behind the fancy printed patterns, readers can also infer the cultural implications on literati's lifestyle in late Ming Dynasty. The patterns can be divided into three categories: literati’s refined plaything, vignette paintings, and metaphors. The literati's refined plaything explains many aspects of Hu's daily life, interactions and preferences as a literati. Among the patterns, there are many antique artifacts, jade, ceramic, and flora and fauna specimens collected by Ten Bamboo Hall and loved by Hu. The scenery patterns present Hu's love to the nature and desire for a detached life. The second type, vignette painting, reveals the aesthetics of the literati and their preferences in painting. Patterns like stones, plum blossom, bamboo, pine tree and orchids are largely found in the book. In Chinese culture, they are associated with the literati class because of their good qualities. The last type, metaphors, are mostly connected with the social and political environment of the time. In Ming Dynasty, the Confucianism was further strengthened, and relative thoughts were distributed through publication of books. Hence, the literary class focused on the spread of moral cultivation. In the "Ten bamboo Hall Poetry Paper", many characters in the popular stories at the time were found. Most of the stories were aim to advocate certain qualities, including filial piety, diligence, talent appreciation, friendship, humility, indifference to fame and fortune, and honesty. As a literati, Hu's propaganda and advocacy of the moral theories were not intended to defend the ruling class's regime rule, but to prove their existence in an implicit way of expression.[5]

Overseas Impact

Though this book was famous in China, it also has a great influence in Japan, and after woodblock water printing was spread to Japan from China, Japanese did a great job in promoting this technique and adapting it to their own works of culture. This book is also regarded as a treasure by the Japanese. The 1952 version book at Kislak center is an example: it was donated by a collector that exclusively collects Japanese items. In recent years, there were also many exhibitions about the book, aiming to facilitate the communication on this book between China and Japan. Starting from the 1940s, this book was translated, printed and published in many Western countries such as the US, Switzerland, and Germany.