British Family's Recipe Book: 1747-1807

British family collection of recipes, 1747-1807 contains multiple formats of recipes from the mid 18th century to the early 19th century England, collectively handwritten by three families: the Cusloves, the Sackers, and the Nicholls. Encompassing a broad range of recipes, from culinary to medicinal, the recipe book contains not a single, unused page. Following its creation in 1747, the collection was expanded upon and exchanged between the three families for sixty years. Now, collection resides in the University of Pennsylvania's Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts after being purchased by the University of Pennsylvania in 2020.The vellum-bound recipe book serves as the main thread of the collection and is where most of the recipes and distinct hands appear.

Genre and Historical Context

The History of Recipe Books

Recipe books,also called cookbooks, are defined as books containing culinary recipes, as well as instructions for kitchen and household techniques.[1] The specificity of recipes presented can also vary as some books offer detailed recipes while others simply serve as memory aids for individuals already familiar with the dish.[1]

Early cookbooks were symbols of wealth or royalty as the oldest recipe collections emerged from the royal families of monarchs and princes in the 15th century.[1] At this time, the books were not written with the intention of sale but were instead written as aide-memories for the royal chefs responsible for producing delicacies that matched the grandeur of the court culture.[1] With the introduction of printing technology in the mid-15th century, the audience for the genre of recipe books gradually broadened.[1] Particularly, publishers began to publish recipe books with the housewives in mind, who had immense responsibilities at their estate, entrusted with not only the cooking but also the management of the entire household, including the servants.[2] Cooking books were also published for the middle class that presented simpler recipes suited for smaller budgets, such as the Plain Cookery Book by Charles Elme Francatelli, who was a chief cook to Queen Victoria.[1] The clear-cut divisions of social class are evident in recipe books as publishers added labels such as “for the wealthy” or “for all classes” to signal the class of individuals the book was intended for. [1] The social class distinctions in recipe books have certainly declined, but these historical recipe books provide an important window into everyday livelihood and domestic knowledge of that time.

The Georgian Era

The recipe book, written from 1747 to 1807, is situated in the very middle of England’s Georgian era, an era that saw many changes and uncertainties through the start of the Industrial Revolution, the expansion of the British Empire through war and settlements, as well as the American Revolution. Amid such great changes, it is plausible that the citizens in England also felt great uncertainty about their future, prompting them to cling to what they know is stable, such as food and interpersonal relationships through the conduit of recipe books.

The Family and Social Roles of Recipe Books

Role of Recipe Books in Family

Unlike the published recipe books, family recipe books not only contain the recipes but also memories that are interlaced with the recipes.[3] Meals and families are regarded as mutually inclusive systems, where one cannot exist without the other.[3] In other words, a family meal is the essence in the definition of a family and in producing family bonds. As such, there exist stories within recipes, which could provide a comforting memory, such as a remembrance of a late family member or a happy memory that is associated with a food recipe.[4] A fragile, hand-sewn recipe manuscript written by a woman in an arduous journey fleeing from Europe in 1969 served a more therapeutic rather than a functional purpose, signifying how something so unvarying as food holds significant memories for an individual.[4] Moreover, the preservation of handwriting in recipes serves as a physical memento for the passing life of a family member.[3] Additionally, recipe books play a crucial role in constructing the family’s very identity.[5] An aspect of “paperwork of kinship,” recipe books were collected in addition to essential paperwork of the household, such as financial documents, in the early modern times, as they held records of social connections as well as memories.[5] The family’s legacy of memories and recipes was stored as the physical format of a recipe book, valuable enough to be an heirloom passed down for generations.[6]

Social Roles of Recipe Books

The role of recipe books extends beyond the social construct of a family. Recipe books served as records of social networks and functioned as a way to maintain interpersonal relationships.[6] Recipes in early modern times were freely exchanged, operating under the mindset of “bring it home first, decide what to do with it second.”[6] Once a recipe was received by an individual, reciprocating the act of kindness by giving a recipe of their own was the social norm.[6] After acquiring the new, shared recipes, recipe experimentations that followed were the drivers of the scenes of knowledge-making and exploration.[6] Through such recipe trials and errors using recipes gained from their social networks, householders gained a deeper knowledge of not only food but also of sickness and health.[6]

The vellum-bound recipe book could be an example of either a family heirloom or a physical substrate representing the action of a recipe exchange. This cannot be exactly determined because the precise relationship between the three families that contributed to the recipe collection is unknown. Nevertheless, the recipe book certainly served as an important substrate in keeping the families together through their shares of knowledge throughout sixty years.

Material Analysis

Substrate, Binding, and Format

-

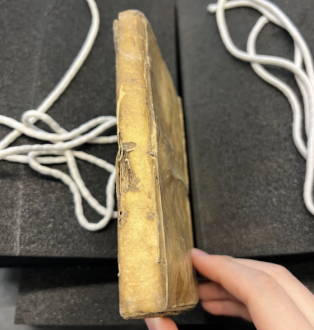

A tear in the spine with a string protruding from the tear

-

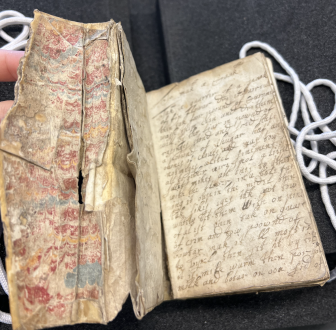

The front pastedown, featuring marbled paper and a self-made pocket

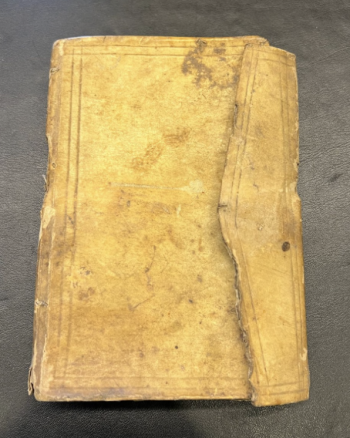

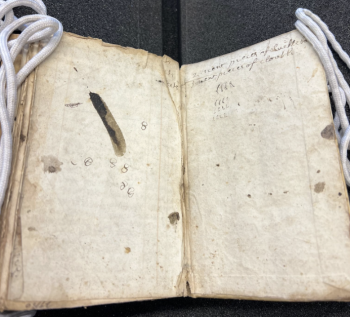

The recipe book is vellum bound, which has been yellowed and marked with darkened splotches due to its antiquity. The size of the book is comparable to the size of a hand, facilitating its easy transport and usability. The book features a cover flap that secures the back cover, most likely used to secure the book closed or to serve as an aesthetic design. There are no inscriptions on the cover of the book. The substrate is visibly damaged and worn out, as evidenced by the tear in its spine. The string binding the book is also not secure as there is a loose string sticking out of the tear in the spine and the spine is becoming separated from the pages.

The recipe book consists of 12 leaves per gathering. The exact bibliographic format cannot be determined because the book is not a printed book that underwent the process of machine printing. It appears that the book was not rebound because the front and back pastedowns are made of the same materials as the other pages. The pastedowns are wrinkly, suggesting that too much glue was used when attaching the paper or that the pastedowns were pasted at home by an individual with less experience. Additionally, a marbled paper is used in the front pastedown, most likely after the book was first bound, further suggesting that the book underwent self-repairments by the individuals using or writing on the book. A unique feature of this book is found at the front pastedown through the presence of a “pocket,” created by two layers of pastedowns with the top cover not completely attached, leaving an opening for its use as a pocket. Also likely self-made, the pocket could have been created to store shared recipes exchanged between the family members and the community.

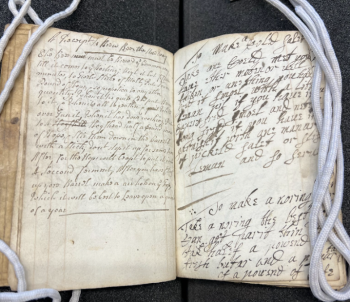

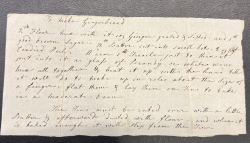

The recipe book identifies a total of four distinct hands, two of which are identified as Elizabeth [Sacker] and William Cuslove. The relationship between these individuals is unknown, but they are assumed to have been in the same family or household. However, the recipe book was certainly integrated within the household as different hands were found right after one another. In addition, the same names and hands appear on multiple entries. The book is entirely handwritten, with no single, unused page. Accompanied by a heading that describes what the recipe is for, every entry elaborates on either culinary or medicinal recipes. Examples include “to pickle mushrooms,” “to make almond pudding,” and “a receipt for the bite of a mad dog.” In the creation of recipe books, medicinal entries were a crucial component as the primary area of medical treatments was sourced from the kitchen in the early modern times, always preceding interventions by the physician.[5] The recipes broadly describe the sequence of steps with rough measurements, such as “take to every Gallon of water, a pound of honey, and half pound of the beast [sic] powder sugar…” for the recipe “To make meat.”

The well-worn recipe book bore signs of heavy use, with certain pages more discolored and wrinkled than others, indicating frequent access. Notably, there is evidence of intentionally ripped-out pages, as the cuts are clean. This evidence can be tied back to the role of recipe books as promoters of social interconnectedness, affirming an age-old human desire to bond through sharing. Moreover, the back pastedown shows evidence of pen trials and a shopping list, which writes “2. New pieces of buckle back 3. New pieces of clooth [sic].” The presence of writing even on the pastedown indicates that the writer sought to make the most of the book's pages, as paper was a costly commodity until the invention of steam-driven paper-making machines in the 19th century.[7] Furthermore, the presence of a shopping list suggests that the recipe book was an integral part of the daily life of this household and kept close at hand for easy reference.

From observing the substrate and the content of the recipe book, the book not only provides a detailed insight into the life of an ordinary household in England in the Georgian era but also reveals the role the recipe book played in the social lives of the contributors to the recipe book, as evidenced by the deliberate cuts of recipes.

Provenance and Significance

Acquired from Dean Cook Rare Books (Bristol, UK) in 2020, the collection was made possible with assistance from the Edgar Fahs Smith Memorial Fund. Established in 1932 by Dr. Smith's widow, the fund honors her late husband, who left a lasting legacy at the University of Pennsylvania as a Professor of Chemistry, Vice-Provost, and Provost over 44 years.

Comprising sixty years of recipe collections, the vellum-bound recipe book is a repository of various fields -- culinary, household, and medicinal -- passed down and shared between people in different families. The recipe book is part of a larger collection of recipes amassed by three families, consisting of the vellum bound book, a stitched recipe booklet, and numerous loose sheets of recipes. The loose sheets of recipes, alongside the recipe book, provide direct evidence of recipe exchange likely shared among family members. These recipe books represent a unique genre, capturing social interactions in simple physical forms of ink and paper while embodying the universal language of food. Delving beneath the layers of ink and paper, a contemporary reader can uncover valuable insights into the culture of recipe exchange and collection, as these recipes served not only as memory aids for future reference but also as a means to maintain social connections and preserve cherished memories. This collection of recipes provides a glimpse into the daily lives and household practices of ordinary, middle-class Georgian-era households, which might have served as practical cooking guides for that household, but now functions as artifacts of domestic life and social interaction in the 18th century.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Notaker, H. (2017). A History of Cookbooks: From Kitchen to Page over Seven Centuries. Berkeley: University of California Press. https://doi-org.proxy.library.upenn.edu/10.1525/9780520967281

- ↑ Woodbridge, L. (1988). Gervase Markham. The English Housewife. Ed. Michael R. Best. Kingston-Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1986. 40 ills. + lviii + 321 pp. $35. Renaissance Quarterly., 41(1), 130–132. https://doi.org/10.2307/2862254

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Sava, E. (2021). FAMILY COOKBOOKS - OBJECTS OF FAMILY MEMORY. Metacritic Journal for Comparative Studies and Theory, 7(1), 98-115. Retrieved from https://proxy.library.upenn.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/family-cookbooks-objects-memory/docview/2616233451/se-2

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Wall, Wendy. Recipes for Thought : Knowledge and Taste in the Early Modern English Kitchen, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.proxy.library.upenn.edu/lib/upenn-ebooks/detail.action?docID=4321857.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Leong, E., & Pennell, S. (2007). Recipe collections and the currency of medical knowledge in the early modern 'medical marketplace'. Medicine and the market in England and its colonies, c.1450-c.1850 () Palgrave Macmillan. Retrieved from https://proxy.library.upenn.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/books/recipe-collections-currency-medical-knowledge/docview/36930161/se-2.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Leong, E. (2018). Recipes and Everyday Knowledge: Medicine, Science, and the Household in Early Modern England. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. https://doi-org.proxy.library.upenn.edu/10.7208/9780226583525.

- ↑ Carey BJR. Paper and Papermaking: Some Notes on the History of the Art. Medicine, Science and the Law. 1969;9(1):47-50. doi:10.1177/002580246900900110