Bartholomew Fair

Bartholomew Fair is a comedy written by the English playwright Ben Jonson, first performed by the Lady Elizabeth’s Men at the Hope Theatre in London in 1614.[1]

Background

Stage History

There are just two performances on record from Jonson’s lifetime, the second performance being shown for the court in Whitehall and King James on the night after the first performance. With a text almost twice as long as the average play in this period and a large cast of thirty-six named characters, Bartholomew Fair is “the most ‘occasional’ of Jonson’s plays”, implying the existence of special occasions for its performance and within the story itself.[1] In fact, the play’s single-column layout and lavish use of ornaments, illumination, scene divisions, and title pages imply that Jonson intended on printing his plays not as “a script for performance, but a literary work mediated through the dignity of print, in keeping with Jonson’s practice of writing plays that were much too long for performance in full and were destined to have an existence independent of the theatre, however well they adapted to the stage.”[2]

History of Jonson's Folios

Jonson’s first folio entitled The Workes of Benjamin Jonson was published in 1616 by William Stansby, consisting of a collection of Jonson’s plays and poems. In 1631, a second volume of Jonson’s works was printed by John Beale for publisher Robert Allot as a collection of three plays: Bartholomew Fair, The Staple of News, and The Devil is an Ass.[3] Given their continuous signatures, Jonson envisioned a distinct folio volume with the three plays printed in alphabetical order with recent masques and poems included at the end.[4] However, very few copies of this second folio were distributed following their printing in 1631. Allot and Beale were both well-known contributors to England’s book trade at the time; Allot was a publisher of Shakespeare’s Second Folio and Beale was a master-printer and senior-member of the Stationers’ Company. Despite their potential, Beale’s printing left Jonson greatly dissatisfied with his work, evidenced by a letter that Jonson sent to his patron William Caventish, Earl of Newcastle, in 1631 with a copy of The Devil is an Ass:

"It is the lewd printer’s fault that I can send Your Lordship no more of my book done. I sent you one piece before, The Fair, ... and now I send you this other morsel, the fine gentleman that walks in town, The Fiend; but before he [Beale] will perfect the rest, I fear, he will come himself to be a part, under the title of The Absolute Knave, which he hath played with me. My printer and I shall afford subject enough for a tragicomedy, for with his delays and vexation I am almost become blind[.]"[2]

With inaccurate punctuation, wrong page numbers, misspellings, and other errors of detail riddling the pages of Bartholomew Fair, Jonson’s exasperation for Beale’s carelessness are not without strong basis. Even with widespread evidence of stop-press corrections, there are about 400 to 500 uncorrected errors across eighty-eight pages, with over twenty errors on some pages. For reference, the first edition of the King James Bible had 350 slight errors.[2] Production stopped after the three plays were printed, with no title page for the volume printed until 1640, when Jonson's The Second Volume was finally issued to the public, presented with a reprint of Jonson's first folio from 1616 and added texts such as masques and other plays.[5]

Ownership

Following Robert Allot’s death in 1635, ownership of his copies were passed onto his widow Mary Allot. When Mary Allot planned to remarry outside the Stationers’ Company, which she believed would invalidate her ownership of Robert Allot’s copyrights, her future husband Philip Chetwin requested a transfer in ownership to Andrew Crooke, a bookseller and “servant” of the Allots, and John Legatt, a printer. Crooke and Legatt entered a list of titles from Allot into the Stationers’ Company in 1637, including Bartholomew Fair. Only in 1637 was Bartholomew Fair finally published, in its rejected 1631 form.[3]

Material Analysis of the 1631 Codex

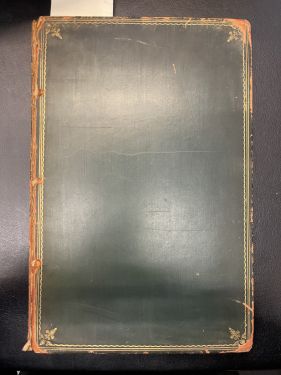

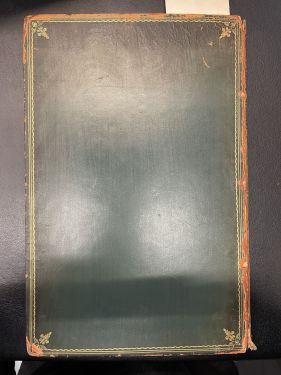

This copy of the 1631 codex of Ben Jonson's Bartholomew Fair is from the Rare Book Collection Folio of the Kislak Center for Special Collections at the University of Pennsylvania with call number EC6 J7384 631b. An digital scan of another copy of the 1631 codex is available by the Library of the University of California Davis. Starting from the unopened book, the copy appears to be rebound by bookbinder Alfred Smith, whose stamp is on the verso of the front free endpaper, likely during the early 20th century at the request of the last owner, Henry H. Bonnell (1859-1926).[6] Bonnell was an author and American book collector who gifted this copy of Bartholomew Fair to the University of Pennsylvania, his alma mater and where he served as a member of the Board of Managers of the Museum. [7]

External Structure

The book is a traditional codex bound by full green morocco leather wrapped around pasteboard, with gold-tooled triple-fillet border on the front and back covers and gold-tooled cover edges and turn-ins.[6] There are three sites where the binding cords are visible near the spine. There is significant wear on the outside of the book, with fraying binding cords, exposed and separated pasteboard, and the front and back covers almost completely detached from the spine, being held together at the binding sites only. The top half of the back cover has a wrinkly texture, suggesting some water damage. The center of the front and back covers are smooth and green with little damage, just a few small scratches revealing the orange leather beneath. The top edge is decorated with gold, while the fore-edge and tail/foot are not. The headband consists of alternating white, green, and brown thread in great condition.

- External Structure of Bartholomew Fair (1631)

-

Front Cover

-

Spine

-

Back Cover

- Edges of Bartholomew Fair (1631)

-

Top Edge (Gold-decorated)

-

Fore-edge

-

Top Right Corner (Top & Fore-edge)

-

Tail/Foot

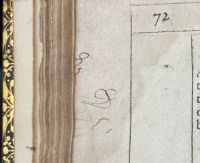

Signatures

The signatures for this book are A6 B-M4. The book is a folio consisting of a preliminary, the first gathering, that is three bifolia nested together, and twelve gatherings of two bifolia resulting in four leaves and eight pages per signature.[8] The first page of the first gathering is missing from this copy. To help the binder correctly collate these sections together, most rectos had signature marks and most pages included catchwords at the bottom right corner of the page.[9] Usually, plays were printed in a smaller quarto format, while this book was printed as a folio of just 88 pages.

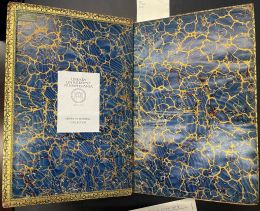

Endpapers and Flyleaves

Opening the front cover of the book, the marbled endpapers with blue, gold, red, and white colors are striking to the eye. The pastedown, the side that is attached to the cover, is smaller to leave room for the leather turn-ins and gold-decorated edges. Additionally, there are two bookplates, a small one in the top left corner for the Rare Book Collection and one in the center for the Library’s Henry H. Bonnell Collection. The marbled flyleaf is pasted to a blank page. The blank flyleaves were certainly added during the rebinding process, as these pages used wove paper while the book block used laid paper, with the lines most visible in front of bright light. The back endsheet is equivalent to the front with its marbling and decorated edges.[9]

Internal Contents

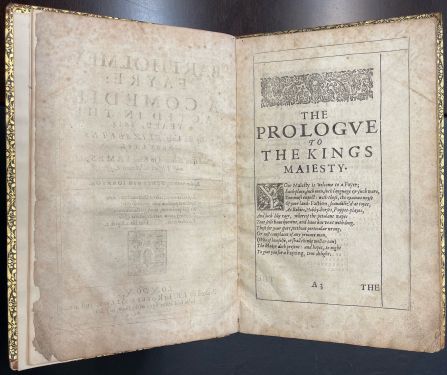

Title Page

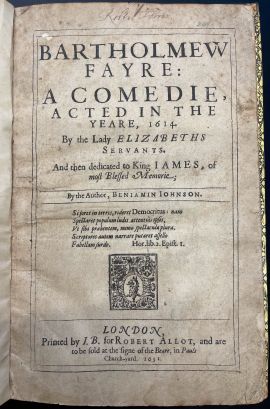

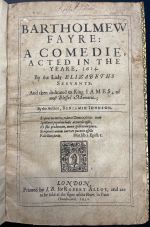

Flipping past the flyleaves reveals the title page of Bartholomew Fair and the first page from the 1631 printed copy. A classic title page in the post-incunable period, the title page uses serif font of various sizes, spacings, and styles. In addition to the title, year and company of the first performance, dedication to King James, and authorship, the title page includes a Latin motto, a printer stamp by John Beale, and an imprint describing the printer I.B. (John Beale) for publisher Robert Allot, “to be sold at the signs of the Beare, in Pauls Church-yard” in 1631. [10]

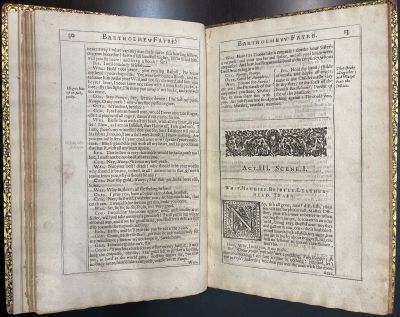

In terms of navigational aids, there are page numbers printed at the top corners and a running head of the book title on each page. There is no table of contents or index sections in the book. However, each transition between scenes and acts is clearly marked with a woodblock-printed banner (between acts only), larger text introducing the act number, scene number, and setting, wider spacing, horizontal lines, and historiated/decorative initial letters. Of note is the factotum initial of the beginning of Bartholomew Fair (Act 1, Scene 1), depicting Eve’s handing of the apple to Adam, a common Beale fingerprint.[2]

Anatomy of the Page

Each page is lined with a clear border and includes side margins to describe actions taking place in the play. Additionally, the play is printed using italics for emphasis, and different characters’ parts are denoted by starting on a new line and by using indentation and all-capitalized letters of the character’s name to precede the script.

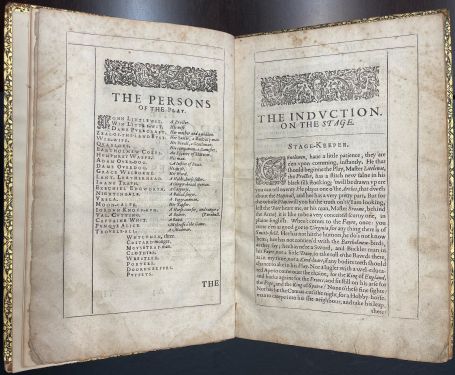

Before the Script

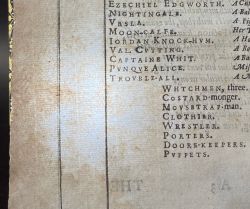

Before the actual script of the play, there are three sections: “The Prologue to the King’s Majesty”, “The Persons of the Play”, and “The Induction on the Stage.” Each includes the traditional woodblock-printed header, larger title, and decorated/historiated initial.

-

The Prologue to the King's Majesty

-

The Persons of the Play and The Induction of the Stage

The last page of “The Induction” has a few features of note. First, the text is middle aligned and arranged to form a triangle-like shape. Additionally, there are two horizontal lines in the white space, between the catchword “BARTHOL-”. This middle align is a common style of the end of preliminaries. This arrangement of text and the horizontal lines would help keep the paper stable when printing, as too much white space could cause the paper to shift while printing. Furthermore, if one takes a careful look at the catchword, the borders/edges of the typeface are visible (also known as an "inked shoulder"), suggesting that the ink type was pressed too hard during printing.

Use and Wear

There is plenty of evidence of use and wear within the book. Towards the end of the book, most pages show water damage around the bottom. Also observed are holes at the top of the book near the spine, probably caused by bookworms who were attracted to the spine area where they could feed on the glue. Most of the pages’ edges are worn, but there are two specific pages with the most major damage. The largest ripped page does not appear to affect any of the printing. The last leaf of print appears to have been amended with a paper strip on the side, though who might have fixed this page is unknown.

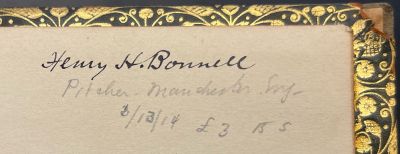

Marginalia

At the top of the title page is the ownership inscription of a Robertus Thorne (“Robbus Thorne”), although his identity and background are not clear. There is just one other form of written marginalia in this book on the back free endpaper, of Henry H. Bonnell’s autograph in pen and pencil recording of his purchase of the book, which appears to have taken place on June 13, 1914 for 3 pounds and 15 shilling.

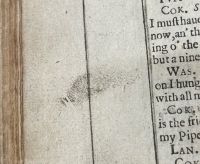

There is very little marginalia in the book—no writing is found within the pages of the play itself, only the title page’s owner inscription and the back free end paper’s collector inscription and purchase details. However, there is a fingerprint in ink, presumably from the printer, in addition to pen scribbles in the margins, possibly from an owner or reader.

Printing Quality

To Jonson’s point, the quality of Beale’s printing is inconsistent and contains many errors. For example, consecutive pages were inconsistent in thickness and quality of the border lines (bottom left photo). The bottom picture is highlighted by Creaser as having significant errors that affect the meaning of the text. From L2r to L3v (pp. 75-78), which had to be re-set late in the printing run, there were four words omitted, three meaningful misspellings, and forty other changes, introducing even more errors from the first setting. Two pages from this section are shown below.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Creaser, John. “Bartholomew Fair: Stage History.” The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Ben Jonson Online.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Creaser, John. “Misprinting Bartholomew Fair: Jonson and 'The Absolute Knave.'” In A Concise Companion to the Study of Manuscripts, Printed Books, and the Production of Early Modern Texts : A Festschrift for Gordon Campbell, edited by Edward Jones, 209-228. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2015.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Williams, William P. “Chetwin, Crooke, and the Jonson Folios.” Studies in Bibliography 30 (1977): 75–95.

- ↑ Creaser, John. “The 1631 Folio (F2(2)): Textual Essay.” The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Ben Jonson Online.

- ↑ Loewenstein, Joseph. Ben Jonson and Possessive Authorship. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Franklin Library Catalog, University of Pennsylvania.

- ↑ "Mr. Henry H. Bonnell." The Museum Journal XVII, no. 4 (December, 1926): 433-433. Accessed April 06, 2022.

- ↑ Creaser, John. “Bartholomew Fair: Textual Essay.” The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Ben Jonson Online.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Borsuk, Amaranth. The Book. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2018.

- ↑ Lesser, Zachary. Renaissance Drama and the Politics of Publication: Readings In the English Book Trade. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2004.