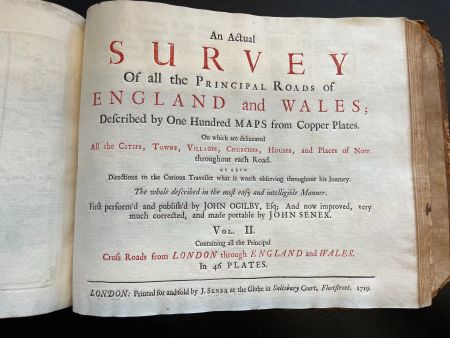

An Actual Survey of All Principal Roads of England and Wales

In 1719, John Senex published An Actual Survey of All the Principal Roads of England and Wales, which served as an updated version of the monumental Britannia, 44 years after its original publication by John Ogilby in 1675. Britannia was the first road atlas of England and Wales to be based on precise measurements and the one inch to one statute mile scale.[1] The road atlas covered over 7,000 miles of roads and 100 individual strip road maps which were an innovation by Ogilby.[2] Senex’s version of Ogilby’s strip road atlas brought necessary changes that corrected route measurements and made the atlas portable, both of which made it a consumer success and an enabling factor in the growth of travel and tourism in Europe.[2] The copy being reviewed and used for pictures in this wiki is from the Kislak Center for Special Collections at the University of Pennsylvania.

Historical context

John Ogilby

John Ogilby (1600-1676) was a Scottish translator, cartographer, poet, printer, publisher, and innovator best known for his work Britannia, an innovative road atlas encompassing 7,500 miles of routes throughout England and Wales. After spending much of his early life focused on theater and translating the classicals of Virgil, Homer, and Aesop, Ogilby turned his focus to his interests in geography and mapmaking. In response to the Great Fire of London in 1666, Ogilby was placed on a team led by Robert Hooke to settle land disputes throughout the city.[2] During this period to help solve the disputes, Ogilby is credited with his survey of London.[3] With the success of his survey and subsequent atlases of different regions of the world, King Charles II appointed Ogilby to be Royal Cosmographer and in charge of producing an atlas of Britain, which would turn into his Britannia.[2]

Britannia

Text

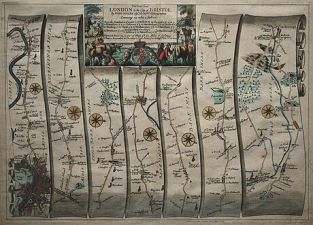

Britannia is Ogilby's road atlas of England and Wales published in 1675 which highlights 100 of the most major routes of using Ogibly’s innovation strip map layout. The atlas is credited in the field of cartography for several designs and measurement methods that altered the ways future maps would be created.[4] To garner support for this project, Ogilby pitched his idea for a precise road map of the most important routes through England as a method of improving “commerce and correspondency” throughout King Charles II's sovereign land.[2] Covering over 26,000 miles and taking five years to produce, the survey resulted in the first version of Britannia weighing almost 8 kg.[5] Due to the vast size of the land to be surveyed and methods used, Ogilby’s fundraising was critical for Britannia completion.[3] It is estimated that the cost of the survey was no less than £20,000, of which King Charles II paid at least £500 and another £500 on behalf of his royal consult.[6] The list of subscribers that stood alongside Charles II in funding the projects were largely wealthy aristocrats and academic societies, namely the Royal Society.[3]

Significance in cartography

Due to Britannia, Ogilby is viewed as not only an integral cartographer in the standardization of English mapmaking but also the greater history and standardization of worldwide mapmaking, usage, and circulation.[4] For one, his work was the first road Atlas of England and Wales produced using “strict dimensuration” as opposed to the methods of “tracing of Notionary Roads upon imperfect charts at minute scales” that were common at the time.[2] Ogilby and his team of surveyors utilized the surveyor’s wheel as opposed to standard chain measurement that required two men to operate.[2] Using his method of measurement, Ogilby is seen as the innovator of scaling maps at one inch to one statute mile, or 1:63,630.[1] During the late 17th century, the definition of the mile varied locally between the towns and counties of England, but due to the popularity and widespread circulation of Ogilby’s strip maps, he is seen as a large reason for the standardization of the statute mile as 8 furlongs, or 5,280 feet. Another key factor in the success of Britannia is its usage of strip maps, an Ogilby invention, which made wayfinding more user-friendly and attracted a broader consumer base of tourists and traders.[2] His depiction of hills and gradients, notable houses and stores, and bridges throughout his strip maps also enhanced the reader’s experience and ease of navigation.[4]

King Charles II, King Louis XIV, and Britannia conspiracy theory

Some scholars have questioned the intentions of King Charles II's support that gave Ogilby the ability to complete his survey and atlas. The theory proposes that Charles II's main intentions for the production of Ogilby’s atlas were strategic for military purposes.[7] These historians revolve their argument around the well-documented Secret Treaty of Dover of 1670.[5] The treaty was essentially a plan for Charles II to publicly announce his conversion to Catholicism, and in return, be given financial and military support from King Louis XIV of France, his cousin, in a war against the Dutch during the height of the Anglo-Dutch Wars.[5] The speculation about a possible connection between the treaty and the creation of Ogilby’s Britannia arises from the very first engraved route of the atlas from Aberystwyth, an insignificant port town in Wales, to London.[7] Considering that the Treaty of Dover would require Louis XIV to send 6,000 French troops to protect Charles II in the event of a rebellion and the questionable decision to include a route from Aberystwyth to London while excluding a route from the more important Liverpool to London, some historians have hypothesized that Charles II directed Ogilby to include the route as a clear path for French troops to make an undefended march to London.[5] Despite a few avid supporters of the theory, many scholars still remain skeptical and argue against it.[8]

John Senex

John Senex (1678-1740) was an English publisher, cartographer, and astrologer best known for his maps, atlases, and globes. For most of his career as a bookseller, Senex operated his business on Fleet Street in London where he sold everything from original maps to reprints and translations of European writers mathematics, chemistry, philosophy, and many other topics. Due to his impressive network of relationships with many influential writers, scientists, and publishers in addition to his accomplishments in globes and mapmaking, he was elected a fellow of the Royal Society in 1728.[9]

An Actual Survey of All the Principal Roads of England and Wales

Text

In 1719, John Senex published An Actual Survey of All the Principal Roads of England and Wales, which is his “improved, very much corrected” and portable version of John Ogilby’s landmark strip road atlas, Britannia, which was first published in 1675 with the support of King Charles II and many academic subscribers.[2] Printed in London, Senex sold his updated version of Ogilby’s atlas at his bookstore at the Globe on Fleet Street in the Salisbury Court neighborhood of London. Senex’s version is one of the earlier renditions of Ogilby’s original work that spurred a multitude of newly published versions updated for accuracy and portability that would flood the English book market throughout the 18th century.[2]

Book as a physical object

Substrate, format, & structure

The paper that comprises the pages of the book is made from linen rags that were made into a pulp and placed on a wire mesh to form the sheet. This method of papermaking was the most utilized type during the printing of the book in 1719. The pages' thicker feel, off white color, and visible chain lines are key clues that point to their linen rag substrate. Unlike many other books both contemporary with this one as well as modern ones, the codex is longer than it is tall. The book measures about 11 inches wide by 8.5 inches tall. Considering the unique dimensions, layout, and many plates used to produce this book, it is most likely each page is a single leaf bound together at the spine of the book. Looking closer at the edges of the pages with the strip maps, there are clear plate marks that have been imprinted on them by the engraved plates used in the printing process. These plate marks, in combination with the freely drawn lines and smoothly written town names throughout the 100 plates, support Senex’s claim of using etched copper plates, also known as intaglio printing. The entire book is encased with a firm cover that appears to be a sort of pasteboard that is covered in leather. The leather has decorative stamping on both the front and back. This type of binding appears to be contemporary with the printing and publication of the book.

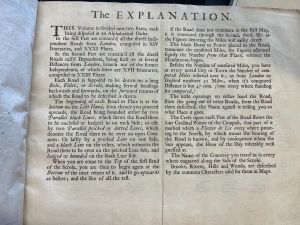

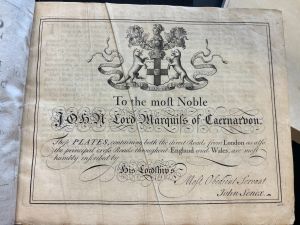

The book contains an explanation page on how to properly use the maps and tables within it. There is also a table of contents with the pages on which a city could be found. To help the reader navigate throughout the book as well as utilize the table of contents, each page has a page number in the bottom right corner. Based on the explanation page and its directions, the book does not assume much of the reader, only the skills that they can read and keep track of simple measurements such as miles traveled. The maps themselves are laid out in strips that mimic the point-of-view of the reader and give landmarks such as creeks, towns, or even paper mills. Because of this, the reader should have an easier time navigating as the book tells them to walk 2 miles until they must turn left after a brook, for example. There is a title page as well as a dedication page that dedicates the work to John Brydges (1703-1727), Marquess of Carnarvon. The title page lays out the purposes of the book as an updated version of John Ogibly’s original version of the roads of England and Wales.

Readership & Circulation

As for this specific copy of Senex’s road atlas, it does not really have marginalia or annotations for any past readers. The only written notes in the books appear to be from the library who stored it and placed call numbers or other signifiers on the flyleaves at the end of the book. The lack of marginalia may suggest that the book was not regularly used or that it could have possibly been the original owner’s preference that it was not written in. There does not appear to be any asemic marks throughout the book. This could point to similar reasons as discussed with the lack of marginalia/annotations. Before the Kislak Center for Special Collections at the University of Pennsylvania owned the book, it appears by the bookplate inside the front cover that it was owned by William Constable.

Significance

The printers and cartographers such as Senex who released updated and portable versions of Britannia played an instrumental role in the growth and development of travel and tourism throughout England as well as the rest of Europe.[2] During the late 17th century when Ogilby published his strip road atlas, the primary people moving throughout England were merchants and traders.[2] There were others who traveled but it was far less frequent due to difficulties of maneuvering the poorly maintained roads and other social factors such as costs and lack of modes of transportation on land. Despite Britannia making road travel in England more reliable, the sheer size and price of the original version acted as barriers for the book to reach a broader, less wealthy audience.[2]

To correct the issues that Ogilby’s hefty and expensive road atlas brought, many entrepreneurs and printers such as Senex sought to bring to market affordable and lightweight versions that could be purchased and more readily used by many.[2] These miniature versions of Britannia gradually flooded the market over the next century with printers taking liberties on which features to include as some only had distance tables and directions without the original strip maps.[10] Of these, Senex was one of the few publishers whose work was so widely popular that it continued to be printed into the late third quarter of the 18th century.[2] As the demographics of those who traveled continued to change from the 17th to the early 19th century, the popularity of An Actual Survey of All the Principal Roads of England and Wales was a contributing factor to the growth of general tourism throughout England. One of the key driving factors of tourism was the rise of Grand Tours, which were a coming-of-age tradition in which young, upper-class European men would travel through both Europe and even to North America as an educational and rite of passage trip.[10] As a direct result of this new consumer audience of tourists, England would begin establishing turnpike trusts which improved, maintained, and built out the road network of England and in turn made national travel safer and more accessible.[2] The concept of turnpike trusts and toll roads in general would spread throughout the world especially to the European colonies to improve the local governments' commerce, communication, and transportation.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 C. Henry and T. Hose, "The Contribution of Maps to Appreciating Physical Landscape: Examples from Derbyshire's Peak District," Geological Society Special Publications, 2015, Vol. 417, pp. 131-155

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 C. Petto, "To Know the Distance: Wayfinding and Roadmaps of Early Modern England and France," Cartographica, Vol. 51, No. 4, 2016, [1]

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 P. Barber, "Enlightened Mapping? Maps in the Europe of the Enlightenment," British Cartographic Society, Vol. 57, No. 4, 2020, [2]

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 E. Johnson, The Cartographic Institute, 2024, [3]

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 C. Saville, "Did John Ogilby Complicitly Map a Route from Aberystwyth to London as Part of Clandestine Plans for a Catholic Invasion of England and Wales, at the Behest of Charles II?" Herefordshire, England, 2019, [4]

- ↑ N. Thrower, The Compleat Plattmaker: Essays on Chart, Map, and Globe Making in England in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, 1979, Vol. 12, No. 4, p. 528

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 M. Kumar, "Why Did Britain's First Road Atlas Take You to Aberystwyth?" The New Statesman, 2021, [5]

- ↑ M. New, "The Nine Lives of John Ogilby: Britain's Master Map Maker and His Secrets by Alan Ereira (review)", The Scriblerian and the Kit-Cats, 2019, Vol. 52, No. 1, p. 110

- ↑ L. Worms, "Senex, John," Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2008, [6]

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 A. Pettinger and T. Youngs, The Routledge Research Companion to Travel Writing, Routledge, 2020, p.337