A German Miscellany

Overview

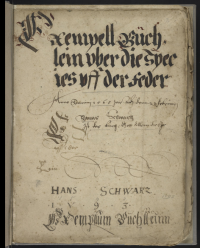

This is a manuscript collection of miscellaneous writings from a German man named Hans Schwartz (also known as Hanns Schwartz) that can be found at the Kislak Center for Special Collections at the University of Pennsylvania[1]. It was written in the mid-to-late 1500s as noted by two dates on one of the introductory pages-1r (1568 and 1593). There are 11 “works” or different entries followed by four business entries about payments and purchases. It's a manuscript that appears to be the personal journal of Hans Schwartz that he kept for more than 20 years.

Historical Context

14th Century Europe

This miscellany was written in Rothenburg ob Tauber in the southern region of Bavaria, Germany. From the middle ages to the late 1800s this city was considered a "free imperial city" which means it was only subordinate to the Holy Roman Emperor rather than a territorial prince or ruler[1]. This distinction gave the city more autonomy than most during this time period. In order to fully understand the context in which this book sits it's important to look at the history and culture of manuscripts in 14th century Europe. The period of 1568-1593 situates itself solidly in the European Renaissance period. Despite the boom in book-printing in Germany during this time, Schwartz chose to write this manuscript. This is due to the nature of the book he was producing. Instead of a novel or history book, Schwartz used his blank book as a catch-all for information he thought was important at the time. Because of this, there is no real cohesion or order to it.

Manuscript Culture in Early Modern Europe

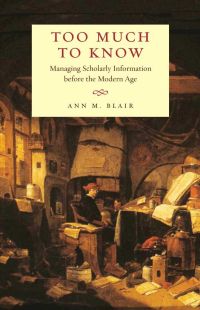

Ann Blair in her book "Too Much to Know : Managing Scholarly Information Before the Modern Age"[2] details the manuscript culture of early modern Europe. It began in Italy in the mid-thirteenth century with the widespread use of paper manufacturing. This meant that materials like paper, ink, and covers were inexpensive and allowed for common people to afford their own blank book for everyday use. Again in Italy, merchants kept books called "ricordanze" and "zibaldone"[2] that documented personal and practical information. These books contained information as miscellaneous as texts, letters, songs, legal sources, and mathematical tables. This practice of keeping personal journals traveled with the merchants and spread to Germany where Schwartz was obviously influenced.

Equally important to the culture of manuscripts is their preservation. For instance, what made this miscellany so important as to have been preserved in the Kislak Collection at the University of Pennsylvania? Blair explains that note-taking was a common practice in early modern Europe and that large collections of notes were seen as keepsakes even if they had no immediate importance. It was normal for an individual to keep his notes in a book format for this very reason. The reason for this particular manuscript's preservation is also explained by the cultural phenomenon of collecting accounts of note-taking[3] . This book was previously sold in 1690 by Helmuth Domizlaff, a German antique book collector[4]. It was then traced to August Merz 1862 and later made its way to the Kislak Collection via one of the library's book collectors.

The 1525 Peasant's War

The 1525 Franconian peasant uprising was referenced multiple times in this miscellany both by Schwartz in the form of songs and a list of peasant fugitives but also as part of a larger historical record that Schwartz copied. The repetition of this event in the miscellany implies its importance to the time period in which Schwartz was living.

The 1525 peasant uprising/war took place in Western and Southern Germany near Rothenburg ob Tauber and was the largest civialian uprising in European history before the French Revolution[5]. It was prompted by increasing peasant discontent with local rulers and princes. It technically began in 1524 as a labor strike but evolved as the peasants demanded better agrarian rights and less oppressive rule from the Swabian League[6]. The Swabian League acted as a military alliance between the German imperial free cities. The peasant uprising caught the league by surprise so much that for the first 6 months of the revolt there was no unified military mobilization. When the league finally did mobilize its armies they were sparse and couldn't be trusted since the soldiers were the very people revolting against the Swabian League[7]. The league ended up suppressing the revolt but not without causing severe casualties to the peasant population and taking economic hits to their cities[8].

This event is significant to the context of this miscellany because of the implications it had on the upper-middle class of German citizens at the time. Given his education level and ability to read, write,do arithmetic, (and the very fact that his book is carefully preserved) I believe Schwartz was in the upper-echelon of German society. The peasant uprising probably impacted his life in that he probably distrusted his servants or knew of others who revolted against the rich and powerful.

Contextual Analysis

Entries 1-11

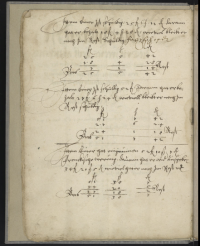

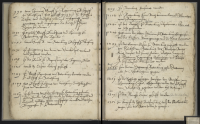

There are 11 “works” or different entries followed by four business entries about payments and purchases. Entry 1 seems to be an introduction to basic math with addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division problems. Entry 2 focuses on agriculture and has multiple short pieces on gardening and the medicinal use of herbs and plants. Schwartz seems to have borrowed writings from Johannes Mesue to talk about barley and rhubarb in this same section. Entry 3 is a group of witty rhymed verses that were probably used in an educational function, and range in topic from religious to civic or patriotic. Entry 4 describes a peasant uprising and beheadings in 1525 in a small town in Bavaria. Historians believe this entry was part of a larger body of work because it appears to be missing the beginning and end. Entry 5 is a straightforward Christian prayer that describes core beliefs. Entry 6 is a poem written by Hanns Weber of Nuremberg that details a two-week flood and tells Christians to be ready for judgment day. Entry 7 is a history of events that are relevant to Rothenburg ob Tauber, the town where this book was presumably written. Entry 8 is similar to entry 4 in that it gives an account of the same peasant uprising but looks at how it affected Rothenburg and gives a list of names of fugitives who escaped the town. Entry 9 is a song about the peasant revolution but names it the “Franconian Peasant War” and describes the events that lead to the uprising. Lastly, entries 10 and 11 concern the marriage of the author (Hans Schwartz) to Margaretta Wolffen. They contain writings from the local deacon (Niclaus Schmidt), a guest list, and business statements from the inn the couple stayed at.

Material Analysis

It contains 86 leaves of paper that were presumably once white but have aged and browned over time. A new, modern library cover has been placed over the leaves so no conclusions can be drawn about form or function from the cover. The edges of the paper are ripped, torn, and worn down leading me to assume this book was frequently used by Schwartz over the 25 years. The original text was written by Schwartz in German with black ink in flowery cursive handwriting but throughout the book, other handwriting and marks can be identified. There is pencil underlining certain words and was also used to make small marginal notes/words and to add page numbers to the upper right corner of pages. These marks are more modern given their use of pencil and most likely were added by a library or collector decades after Schwartz wrote in it.

- ↑ Vice, Roy Lee. THE GERMAN PEASANTS' WAR OF 1525 AND ITS AFTERMATH IN ROTHENBURG OB DER TAUBER AND WUERZBURG: University of Chicago Press, 1984.

- ↑ Blair, Ann M. Too Much to Know : Managing Scholarly Information Before the Modern Age : Yale University Press, 2010.

- ↑ Blair, Ann M. Too Much to Know : Managing Scholarly Information Before the Modern Age : Yale University Press, 2010.

- ↑ Collection Frigts Lut: Les Marques de Collections de Dessins & d'Estampes: Fondation Custodia, 2017.

- ↑ Vice, Roy Lee. THE GERMAN PEASANTS' WAR OF 1525 AND ITS AFTERMATH IN ROTHENBURG OB DER TAUBER AND WUERZBURG: University of Chicago Press, 1984.

- ↑ Sixteenth-Century European Reformations: University of Oregon, 2022.

- ↑ Sea, Thomas F. The German Princes' Responses to the Peasants' Revolt of 1525: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- ↑ Sea, Thomas F. The German Princes' Responses to the Peasants' Revolt of 1525: Cambridge University Press, 2007.