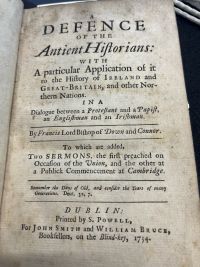

A Defense Of The Antient Historians: Ireland and Great-Britain

A Defense Of The Antient Historians: With Particular Application Of It To The History of Ireland and Great-Britain, and Other Northern Nations In a Dialogue between a Protestant and Catholic, an Englishman and an Irishman, by Francis Lord Bishop of Down and Connor, is a early-modern historical novel applying science and theology to the conflict between Ireland and Great-Britain [1]. Printed in 1734, Dublin, the book acts as an extension of the Scientific Revolution, a cultural movement which caused many to question certain problems with a more critical lens. In 1734, Ireland was fully colonized by Britain and the government of Great-Britain decided upon brutal treatment of its inhabitants. Irish culture was effectively outlawed as the Monarchy sought to assimilate Ireland into their culture. The author of the book, a clergy member who spent both time in Britain and Ireland, wrote the book with the hope of influencing readers to be more sympathetic to Irish people by using a combination of religion and scientific understanding. The book was produced using early modern literature techniques, and had limited circulation. A first-edition copy of the book is stored at the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts.

Historical Significance

Author

Francis Hutchinson, who lived from 1660 to 1739, was a clergyman who most famously wrote An Historical Essay Concerning Witchcraft, a book debunking the religious conflicts around witchcraft. Hutchinson worked at St. James parish in Bury St Edmunds, London, where many witchcraft trials had taken place. His close connection to witchcraft trials, and the advent of the scientific revolution, led him to develop a very critical view of the Church’s dealings with the matter. Hutchinson didn’t release his book condemning witchcraft for years due to pressure from influential members of the Church, but when he did the book served as the nail in the coffin for witchcraft’s acceptance in the modern day. Eventually, Hutchinson was appointed Lord Bishop of Down and Conner in Belfast where he wrote and published A Defense Of The Antient Historians .

Similarly to how he wrote a book condemning witchcraft trials after witnessing them first hand, Hutchinson’s new book covered the conflict he saw between Irish Catholics, who were native to Ireland, and Irish Protestants, who were recent settlers in Ireland, after witnessing their troubles first hand.

Scientific Revolution

Hutchinson was greatly influenced by the development of the scientific revolution with both An Historical Essay Concerning Witchcraft, and A Defense Of The Antient Historians. The scientific revolution had a profound impact on writing, particularly in the areas of clarity, precision, and empirical evidence. Writing became more focused on empirical evidence, with authors using observation and experimentation to support their arguments.[2] In his book regarding Irish politics, Hutchinson used a perspective based on a mixture of science and his own theology. For example, Hutchinson references timelines largely agreed upon in Catholicism, and uses them as empirical evidence to support Ireland's independence. In this way the book acts as a bridge between the theology based writings of the past, and the more empirically based books post scientific revolution.

Quarrel of The Ancients and Moderns

Hutchinson’s novel specifically plays off of the ideals of those who support Ancients ideals from the culturally relevant Quarrel of The Ancients and Moderns debate. In the 17th century, during the European renaissance, it became an essential feature of study to focus on the significance of classical antiquity. These beliefs were in contrast to the current culture of respecting Christianity and unchanging monarchy that specifically stressed that the writings of today were superior due to King Louis XIV and his reign being the greatest kingdom in history. This clashing debate specifically represented people who respected culture that was profound and lasted throughout centuries (supporters of the Ancients) , and those who supported culture that propagandized how great the current french kingdom was (Modernists).[3]

This relates to Hutchinson’s work because he uses Ancient historian ideals to defend Irish importance, hence the title of the book. Hutchinson references the importance of the age of Ireland, using the popular Ancient supporter ideal of long lasting culture being respectable. This makes the novel a product of the current cultural debates of the time, and the title would allow the reader to know what concepts would be used to defend the Irish. The novel also exists as a show of French cultural influence that would come to greatly affect Ireland in the coming centuries.

Substrates and Formats

Material

The material construct is extremely typical for an early modern book made during the 18th century. Each page is made of paper, and the book is assumedly printed by an Intaglio style printer. The novel is of average size, bound by leather, and wrapped in a decorative paper that was made through marbling. A process first created in 10th century Japan, Paper Marbling acted as a decorative design for expensive or rare books in between the 16th and 19th centuries. The process of creating a marble finish revolved around pouring paint mixed with “size” (a surfactant made from tragacanth which was a gum made from dried sap) on top of water, allowing an artist to manipulate said paint before dipping book bindings or pages in the designs. The elegant designs mirror the ripples of water while combining different color combinations. These types of designs were reserved for rare books, and the process of Marbling was kept largely secretive until the mid 1800s. The marbled cover most likely denotes that the book was considered rare and important by whomever originally owned this copy.[4]

Sections, Headers, and Additions

The novel employs a great deal of headings, section titles, and directory features that are supposed to help the reader navigate the book. The format of the book is a dual narrative where the author provides arguments for both Irish and British perspectives in separate sequences. This leaves the reader to follow headers that say “A Defense of Englishman” if they want to read one of the two perspectives, for example. The author also uses section titles to create sections for parts of a chapter. For one section, the author splits the pages with denotations of “First Objection” or “Second Objection” in order to list where his points stopped or started. Lastly, the author adds two outside resources to the text: one being a sermon preached at Occasion of the Union, and the other at a public Commencement at Cambridge. Both sermons were made by and preached by the author, but they both serve different purposes. One is meant to continue the author’s argument in defense of the Irish and the other is in defense of the British. These last additions continue the theme of a split narrative that partitions the book into two disagreeing thought processes.

Besides the back and forth narrative technique being expanded into the format of the novel, the book boasts little out of the ordinary for an early-modern book. There are page numbers, an appendix, titles, a preface, and the next word of the book written at the bottom of the page before it.[5].

Textual Analysis

Content

The novel covers Irish history in its totality from the perspective of the first people to travel to the country after the fall of the tower of Babel. This is also backed up by descriptions of Irish government, culture, and other facets of society. The novel also quotes British historical figures while attempting to correct the false arguments made in defense of Great-Britain's discriminatory actions towards the Irish. While the facts used in the author's argument for the validity of Irish culture are mostly invalid, for example claiming that the Irish deserve respect because they are no longer Pagan or because Irish hills are as old as British hills, the author’s sympathy and respect for Irish people is quite evident. This sympathy was a quite scandalous take to have as the author was both a British citizen and anointed power in Down and Conner based off of British rule. This makes the novel similar to the author’s last work due to both challenging pre-established norms.

Circulation

During the 18th century, Ireland had a flourishing book market centered around the capital City of Dublin where this book happened to be printed by Samuel Powell. Powell, a music sheet printer, produced this book in his shop on Crane Lane.[6] Taking inspiration from French culture, Ireland developed a unique coffee house reading culture that was based on the spread of intellectual books that were printed in Dublin shops like Powell's. These coffee houses were the centers of public debate and knowledge which led to the “Golden Age” of printing in Ireland.

This period also led to a “quality of expertise has never been surpassed” in book binding. Individuals could request certain types of bindings with gilded covers or, most popularly, paper wrapped books that could be designed with marble.

To my knowledge the book did not necessarily have a high circulation due to the content being greatly controversial, and the reader base being small. Those described to have read debate books in Dublin, such as Hutchinson’s, were “gentlemen” which implies a certain level of wealth.[7] The book was eventually adopted by the Capuchin monks of Belfast who included the novel in their libraries. The book was largely targeted at a British audience in an attempt to persuade public opinion away from discriminating against the Irish, so the book may have been an unnecessary read for most Irish inhabitants.

References

- ↑ Hutchinson, Francis, and Samuel Powell. A Defence of the Antient Historians : with a Particular Application of it to the History of Ireland and Great-britain, and Other Northern Nations : In a Dialogue Between a Protestant and a Papist, an Englishman and an Irishman. Dublin: Printed by S. Powell for John Smith and William Bruce, booksellers ..., 1734.

- ↑ Dudley, Fred A. “The Impact of Science on Literature.” Science, vol. 115, no. 2990, 1952, pp. 412–15. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1678182. Accessed 29 Apr. 2023.

- ↑ Burke, P., "The spread of Italian humanism", in The Impact of Humanism on Western Europe, ed. A. Goodman and A. MacKay, London, 1990, p. 2.

- ↑ Easton, Phoebe Jane. Marbling : a History and a Bibliography. Los Angeles: Dawson's Book Shop, 1983.

- ↑ Craig, Maurice. “Eighteenth-Century Irish Bookbindings.” The Burlington Magazine, vol. 94, no. 590, 1952, pp. 132–36. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/870818. Accessed 7 Apr. 2023.

- ↑ Flood, W. H. Grattan. “Music-Printing in Dublin from 1700 to 1750.” The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, vol. 38, no. 3, 1908, pp. 236–40. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25513925. Accessed 29 Apr. 2023.

- ↑ Kennedy, Máire. “‘Politicks, Coffee and News’: The Dublin Book Trade in the Eighteenth Century.” Dublin Historical Record, vol. 58, no. 1, 2005, pp. 76–85. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/30101540. Accessed 29 Apr. 2023.