A British Soldier's Photoalbum of India

British Soldier's Photo Album from Journey through Colonial India

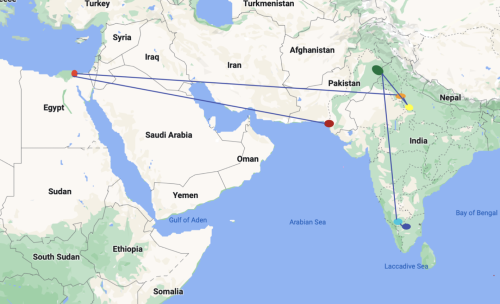

This album was curated by a British soldier from the years 1930 - 1935. The photographs journal the British soldier’s perspective of colonial India. There are 49 pictures of various subjects within modern day India and Pakistan and there are two pictures of Port Said, Egypt. Intricate hand-calligraphed descriptions of the photo subject matter was detailed underneath each picture. The descriptions range from simple geographical location to personal commentary and inside jokes.

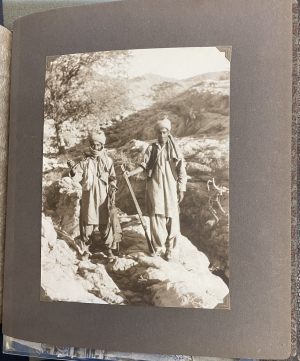

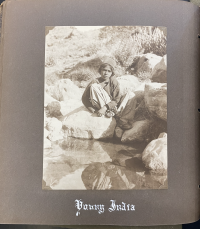

Many of the photographs are of scenic views and architecture and local artistry. There are few depictions of local everyday life and people. Of the few, the portraits appear particularly staged. The book was curated with purpose and care and offers insight into a colonizer’s perspective of his presence in a colonized state.

The creator of the album remains unknown. This photo album is currently at the University of Pennsylvania's Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts collection.

The Book

This album contains pictures from 1930 - 1935. Colonialism in India ended in 1947, so these photographs were obtained pre-independence. Importantly, the pictures include places in both modern day India and Pakistan as they were not yet partitioned at that point.

Photography spread early on in South Asia and German photographers were among the pioneers of early Indian photography. There are records of German photographic studios appearing as early as 1850.[1] Professional photographers ran successful businesses selling photographs to tourists to commemorate their journeys.

At the time of the creation of this specific album, it was fashionable to encapsulate journeys through images, much as it is now, and the British Crown would give soldiers time off from service to photograph colonized areas. These photographs were used as information and representation of the colony. While the identity of the British soldier who created this album remains unknown, much can be extrapolated about his travels, perspective, and interests given the content of the book and the time period and context within which it was created.

The Form and Content of the Album

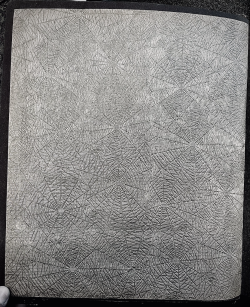

The album itself has a plastic snake leather texture in a dark brown. Yellowed stuffing sticks out of the edges of the frayed cover. There is a thick black rope securing the binding and the inside pages have an animal print pattern. It appears to be a store-bought album that was then carefully hand filled with pictures and annotated. The brand of album, Kodak, is a popular global photography company to this day. The paper is thick and has the feel of cardstock. In between each page is a vinyl sheet designed to protect the contents of the album. The vinyl sheets are impressed with spider webs and spider designs, offering a tactile finish and grip with which to turn pages.

The Signs of Use

There is no marginalia or wear from readers within the battered over. Each photograph is well-preserved. None of the pages are frayed or bent and the photographs have not unattached themselves or faded. Thus, there are no apparent signs of use or viewing. It is possible that the creator of the album intended for the careful preservation of the content by the selection of the specific photo album with a dense, padded cover and vinyl protective sheets. The method of creation even suggests that the creator had longevity in mind: the photographs are neatly glued on every edge and the corners are bracketed onto the pages. Secure and uniform, the form and physical aspects of the book are safeguarding.

Because the content is very well protected and preserved, there is a sense of memorialization and intimacy of the content. This is not to say that the content is without oppressive colonial tendencies: just that it was deeply valued by the creator.

The Photographs

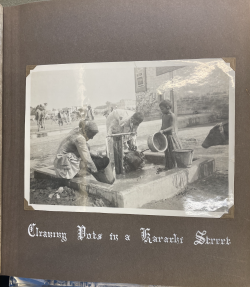

The images range from portraits to close ups of intricate architecture. The photographs transition from glossy to matte over the course of the album. The photograph paper is thick so that when running a finger over the surface of the entire page, it can be clearly discerned what is photographed and what is the original album book paper. Each photograph is meticulously glued to the center of the dark pages. The gluing is seamless and there are thick paper brackets over the corners of the photos. Underneath each photograph is a carefully hand-calligraphed description of the photo. The ink of these inscriptions is white and has a raised texture on the surface of the page. The calligraphy is intricate and looks like it was time-consuming. These descriptions range from simple geographical location to personal commentary and inside jokes.

The content of this album includes a wide variety of subject matter, ranging from architecture and artistry to portraits. The selection of photographs of architectural subject matters is extensive and includes the structures that are the most famous to this day, including the Taj Mahal, the Qutb Minar, and prominent locations. Other particular monuments he chose to curate include the likes of churches, religious structures, and tombs. The album creator was interested in the close up artistry involved in the creation of these buildings and sought to obtain images of arches, pillars, and stonework.

In addition to architectural photography, there were photographs of camels, waterfall scenes, and boats on rivers. These subjects seem to be of particular interest to the creator - there are four separate photographs of camels and one with a close up of the camel’s head and the special caption, “Our friend the camel.” This seems to be comical and perhaps an inside joke among friends.

There were a few portrait photographs within the album as well. People are shown in various ways: from candid in-motion photographs to staged-looking photographs. In one particular photograph of note, the photographer was interested in a scene of two adults and one young child cleaning pots by a well in Karachi. There is a camel and horse drawn carriage in the background and there is writing in Urdu painted onto the walls of a building. A cow sticks its head into the frame of the photograph in the foreground. This is the only view a reader is offered of everyday life in the album: there are no depictions of homes, family interactions, food, or markets in the album. Thus, there is a myopic view of a culture and community.

The final section of the photo album has professionally taken photographs carefully wrapped in plastic tucked before the back cover of the album. These photographs appear to be taken by a professional and purchased and curated by the creator of the album. The one labelled photograph bears the stamp, "Barton Son & Co LTD Photographers." The umbrella company, Barton Son & Co. Pvt. Ltd., is still open to this day. It is based in India and is now primarily a purveyor of silver gift products. [2] The professional photographs included in the back of the album are largely of various buildings and closeups of artistic stonework. The one exception is a group photograph of approximately 100 uniformed men. The words, “Indian Technical Section Karachi 1930” are hand-written in blue ink. It is difficult to discern who took the photographs within the album: it is possible that many were taken by a professional just as it is possible that the curator was an amateur photographer and took the photographs himself.

The Inscriptions

The inscriptions lend themselves to an understanding of who the book is meant for. They seem to demonstrate that this is a personal tome meant to be shared with others. The inscriptions' words share a sense of familiarity with a viewer but it is also understandable for someone who does not know much about the trip.

The creator of the album carefully documents all the places he travels in inscriptions underneath each photograph. His descriptions are largely informational and document a rather convoluted travel journey if the presentation of photographs is supposed to be chronological. Traveling back and forth between Karachi and Delhi multiple times and then to various other locations, this photographer traveled great distances including all the way to Port Said in Egypt and Mysore in Karnataka.

The Colonial Gaze in Photography

The colonial gaze can be described through exoticization, romanticization, sexualization, and more expressed via the lens. Many aspects of this gaze offer themselves as essential contributors to understanding the use of the photograph as ethnographical, racist, staged, and exploitative in this context.[3]

Even the phrase, "colonial gaze" is wrapped up in ideas of looking and the camera. The concept of the "gaze" can refer to the gaze of the camera lens, the person behind the camera, the person in front of the camera, and the person gazing upon the photographs. This multi-faceted complexity mirrors the complexity of the subject matter.

Elizabeth Siegel, a curator of photography at the Art Institute of Chicago, suggests that the real importance of early photo albums is their role as “systems of representation” as indicated by their “ubiquity.” Her research embraces “primary materials long overlooked as marginal or inconsequential and [explores] practices of consumption, reception, and viewing, as well as networks of production.” [4] [5] Thus, the photograph album becomes an important tool in uncovering historical meaning. In the context of colonialism, the subject matter can become tokenized and representational in a way that is oppressive and reductionist of a people, land, and culture.

The Impact

This book offers a unique glimpse into the colonial gaze via an understanding of what a white colonizer and soldier found fascinating about a culture that was foreign and exotic to him. What he chose to preserve, document, exploit, and explore offers insight into the history of colonialism in India. There is much to learn from this text and a further understanding of the historical technology of photography, British India, and the gaze are important steps for the analysis of this book.

The physical form of the book has an impact. The choice to contain these photographs within a photo album as opposed to a hanging photo gallery allows it to be tucked away. Thus, it is convenient and exploited: hidden on a shelf until the creator needs to seem worldly and knowledgeable and mirroring the overarching concept of colonialism. The photo album and consequently the content and culture and people become an intentional tool and means to an end. The content is memorialized but also compact. It is reductionist to the detriment of the subjects and actively benefits the colonizer.

The white calligraphed inscriptions within the album are purposefully descriptive in offering a narrative and giving the feeling of a story book. However, the journey was not a story as real people were the subjects. By reducing images to a phrase within a caption, people, culture, and ideas are pinned down and put behind a glass case. By reducing people to stories, it also removes them from reality and dehumanizes them, subjugating them from new heights. Further, because the captions are intricate and ornate, some focus is removed from the actual photographical content. The author misspells Hindi and Urdu words and names without regard, furthering the form’s impact and clear message that the subject matter is not to be treated with thoughtful care or understanding: it is merely brought into existence for the disposal and use of the creator. Thus, the captions are an essential contributor to the strength of the colonial gaze experienced from this album.

Beyond the physical aspects of the book, the content also contributes to the colonial gaze. The photographer exoticizes and romanticizes the subject matter, and accommodates the subjects to Western culture. The content becomes characterized and humanity and culture are reduced to tropes. This is slightly different from conventional orientalism because it is more private but the aspects of museumification are still highly prominent. The land and people are put on display, both literally and metaphorically. The photographs captured people and culture not as they were living, but in staged and theatrical positions. Thus, its intention is to show people what the White colonizer decided was interesting and exotic and furthers the colonial agenda.

The idea of the afterlife and legacy of an image is important in the history of colonial photography. For example, in post-colonial Gambia, portraiture is discussed as a cherished elegant pleasure that gained new conceptualization after Independence in 1965. It was initially involved as a part of the National Census before gaining greater scope.The burden of portraiture was to make people feel cherished in a similar way to gaining citizenship. Over the years, it progressed into depictions of beauty, advertisements, and Valentine’s Day cards. [6] Thus, photography became essentially linked to ideas of identity and personhood in the wake of colonialism. Photography was a unique source in the afterlife and legacy of this post-colonial state. This is dissimilar to the photography in the photo album discussed here because of the colonial gaze inherent to the work and the time period. While both forms of photography are theatrical and staged, the purpose of this photo album is not to commemorate the people or culture but to bottle it, encapsulate it, and share it with a colonizing homeland. The content is further tucked away in a book, smashed in between pieces of paper, and perhaps wedged between other books on a shelf of other travels and literature. The content is performative in this way and also taken while still under colonial rule, unlike the portrait photography in the Gambian example. Thus, the afterlife and legacy of the photography is very different across the two contexts.

Photographs communicate at the collective human level. A photograph is not sovereign and instead registers everything within the lens as equally important. This, among other inherent aspects of photography, lends itself to the adaptability of the legacy. A photograph can be “[instead of] a repository of attempts at managing the committee’s fantasies of imperial belonging: a repository in which alternative visions of the future (for the equal rights promised by imperial citizenship) could be developed from the same historical negatives.” [7] This idea of shifting content projects a fluid subject matter. Thus, photography is both an art form and a powerful tool and it is learned that photography can tell a narrative and hold sway over perception and history. [8]

A particularly poignant representation of the colonial gaze in this album is in a photograph of three young girls. Two have smiles pasted on their faces while the third looks with narrowed eyes into the lens. All three are balancing clay jugs on their heads and look positioned. The caption below this reads, “Local Beauties at Malir or Karachi.” This inscription is shocking as it describes young girls who cannot be older than twelve years old. The theatrical presentation of ethnography was common in this era of colonial photography and has deep roots in exoticization and the colonial gaze. This idea of exotic also has implicity sexual connotations, made explicit in this specific pedophilic example.

Thus, the author was selective in his curation. Hiding behind light humor and a knowledgeable air, he puts on a careful show. Just as the portraits are staged and theatrical, so is the maker. He becomes the orchestrator and perpetuator of colonial oppression and his own self image.

Notes

- ↑ Derenthal, Ludger, Raffael Dedo Gadebusch, and Katrin Specht, eds. The Colonial Eye: Early Portrait Photography in India. Berlin: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, 2012.

- ↑ Barton,Son & Co. Pvt. Ltd. “About Us.” Barton Son & Co. Pvt. Ltd., https://bartonsgifts.com/pages/about-us.

- ↑ Derenthal, Ludger, Raffael Dedo Gadebusch, and Katrin Specht, eds. The Colonial Eye: Early Portrait Photography in India. Berlin: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, 2012.

- ↑ Mifflin, Jeffrey. “‘Metaphors for Life Itself’: Historical Photograph Albums, Archives, and the Shape of Experience and Memory.” The American Archivist, vol. 75, no. 1, 2012, pp. 225–240., https://doi.org/10.17723/aarc.75.1.y4r1616756345q15.

- ↑ Siegel, Elizabeth. Galleries of Friendship and Fame: A History of Nineteenth-Century American Photograph Albums. Yale University Press, 2010.

- ↑ Buckley, Liam. “Studio Photography and the Aesthetics of Citizenship in The Gambia, West Africa.” Essay. In Sensible Objects: Colonialism, Museums and Material Culture, 61–86. S.l., NY: Berg Publishers, 2006.

- ↑ Smith, Shawn Michelle, and Sharon Sliwinski. Photography and the Optical Unconscious. Durham: Duke University Press, 2017.

- ↑ Smith, Shawn Michelle, and Sharon Sliwinski. Photography and the Optical Unconscious. Durham: Duke University Press, 2017.