A Brief State on the Province of Pennsylvania

A Brief State on the Province of Pennsylvania (A brief state of the province of Pennsylvania : in which the conduct of their assemblies for several years past is impartially examined, and the true cause of the continual encroachments of the French displayed, more especially the secret design of their late unwarrantable invasion and settlement upon the River Ohio : to which is annexed, an easy plan for restoring quiet in the public measures of that province, and defeating the ambitious views of the French in time to come in a letter from a gentleman who has resided many years in Pennsylvania to his friend in London.) is a 1756 pamphlet authored by William Smith. The pamphlet was printed in London and was sold to the public. Smith writes the pamphlet in the form of a letter to an unaddressed recipient in London, and consists of Smith describing and criticizing the policies and actions of the Pennsylvania Assembly during armed conflict with French and Native American forces.

Background

William Smith

William Smith was born in Aberdeen, Scotland in 1727.[1] As an adult, he originally was a teacher in Scotland before transitioning to teaching in the American colonies. He tutored in Long Island before publishing an essay on education that was titled “A General Idea of the College of Mirania”, which was read and appreciated by Benjamin Franklin.

Separately, he was a clergyman in the Anglican Church and became a Reverend in 1754. Due to Smith’s background in teaching natural philosophy and logic, as well as Franklin’s concurrence with his opinions laid out in his essay, the pair collaborated on the establishment of the Academy of Philadelphia, which soon became the College of Philadelphia, and later, the University of Pennsylvania. Franklin and Smith later disagreed over the right of the elected Pennsylvania Assembly to govern over the colony; while Franklin affirmed the power of the Quakers, who were elected to the assembly, Smith held the opinion that William Penn, the proprietor of Pennsylvania, should hold control over the colony. William Smith was publicly critical of the Quaker government, and was especially enraged at their pacifism in the wake of repeated attacks by the French and Native Americans.[2]

French and Indian War

The direct historical context behind A Brief State can be understood through the violence of the French and Indian War, which consumed most of the focus of the American Colonies at the time. The war lasted from 1756 to 1763 [1] and constituted a part of the major worldwide armed struggle between England and France. Around the time that Smith wrote A Brief State in 1755, a group of American and British soldiers were handily defeated while trying to attack the French and Native-held Fort Duquesne. Native American raids into Pennsylvania from the Ohio Valley became common, and the Pennsylvania Provincial Government often did not intervene adequately to protect the colonists who lived near the frontier between Indian and Colonial lands. One example of this was the Penn’s Creek Massacre on October 16, when Delaware Indians attacked the British Penn’s Creek settlement, killing 14 and capturing 11. [3] Afterward, when other settlements on the frontier requested aid from the Provincial Government, these requests were denied, leading to over 2,000 Pennsylvanians being taken captive by Native Americans between 1755 and 1765.[3] Through 1754 and 1755, the Provincial Government repeatedly refused to assert their claim to the Ohio River Valley after encroachments on the territory by both the French and Native Americans, to the anger of many residents, such as William Smith.

Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly

The Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly in Philadelphia found itself in a highly contentious situation. While the British requested further financial aid from the Pennsylvanian government in order to more adequately protect settlements near the Ohio Valley and assert British dominance over the area, the Assembly, led by Quakers, felt that this action was antithetical to their faith. The Quakers were a religious group that preached tolerance and pacifism. Upon the founding of the province of Pennsylvania, a charter was originally granted to Quaker William Penn, who designed the colony with religious tolerance and equality in mind. Even when negotiating with the Native Americans, Penn preached acceptance and tolerance for their ideals. The Quaker Assembly felt that their mission was to carry these ideals forward and preach pacifism in the face of warfare, and this led to the lack of financial support from the body for military operations near the border with the Native Americans.[1] Due to the Assembly’s power to control the finances of the Pennsylvania colony, this translated into little to no additional funds supporting colonists who lived near the frontier of the French and Indian War, and little protection aside from unincorporated citizen militias. William Smith’s pamphlet was written in this context, with Smith’s past criticism and disdain for the pacifism of the Quakers further informing his opinion that the Assembly should take a more active role in supporting colonial settlements in Western Pennsylvania.

Smith's Political Opinions

This pamphlet seems to be a piece of a larger narrative regarding William Smith’s distaste for Quaker ideals, likely stemming from his own upbringing and work within the Anglican Church.[2] This most notably includes the pacifist sentiment of Quakerism, which he seems to vehemently oppose, especially when it led to the Pennsylvanian Assembly refusing to financially support the defensive and offensive military efforts of the British. In this pamphlet, Smith decrees that the encroachments of the French and lack of action by the Assembly is due to several primary issues. First, he ties the inaction of the Assembly to the fact that in his eyes, it had become overly democratic in its decision process.[4] Potentially due to his British upbringing and Anglican ideals, he repeatedly stated that he felt more autocratic leadership, as seen in England, would be beneficial to the colonies as it would be more efficient in protecting the colonists. Second, he takes issue with the fact that the Assembly had the power to directly set the salary of the Governor, who was appointed by the proprietary Penn family. Smith stated in this pamphlet that he saw this ability as a source of inordinate power, theorizing that the Assembly could withhold funds from the Governor as a means of forcing him to support their legislation.[4] Third, Smith paints the Quakers as taking pride in going against the wishes and positions of the British crown[4], implying that their actions could be treasonous. In the main body of the pamphlet, Smith attacks the motivations of the Assembly, using their lack of financial support for British military operations to imply that the Quakers were not concerned with the safety and well-being of Pennsylvanians, or any colonists in general. Smith correctly points out in his pamphlet that it is somewhat antithetical to the purpose of colonial governments that the Assembly would take little to no action when their own borders were encroached on and citizens were killed or taken as prisoners. Smith’s loyalty to the British crown and respect for Anglican ideals are clear throughout this piece and there is a palpable Loyalist slant in his retelling of events.

Substrate and Physical Copy

-

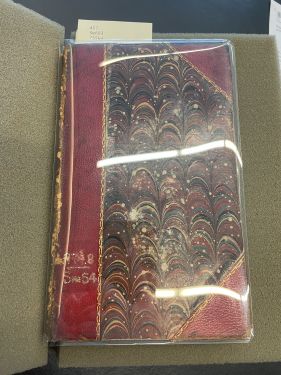

Front cover of the book

-

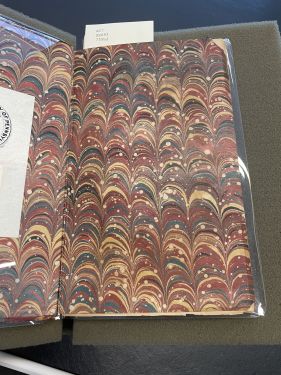

Marbled end page inside the front cover

Marbled Paper

This particular copy of A Brief State is in the form of a bound book. The front and back covers and endpapers are covered in marbled paper with hues of red, blue, yellow, and black. The corners of the covers and the spine of the book are covered in red Moroccan leather. Both of these attributes were seemingly added for a decorative purpose. For some background regarding marbled paper, it is produced using water or another solution which has colored ink floating on top of it. Paper or other substrates can then be placed on top of the surface of this bath, and the ink transfers onto the material, creating marble-like texture. [5] Historically, marbled paper was not seen in America until the end of the 18th century and beginning of the 19th century. When marbled paper first arrived in America, it was imported from European countries such as Britain, Germany, and France, and was not made domestically. As American craftsmen began to learn the craft of paper marbling, the domestic work seen throughout the States was considerably less detailed and more simplistic than the European product. [5]

Applying this knowledge to this pamphlet, it seems that the marbled paper used for the covers and endpapers are of American origin, due to the consistent colors used and highly repetitive and simple design as compared to European counterparts. This would mean that the paper used for the cover and endpapers of this book originated from America in the mid-18th century, hinting that this copy of the pamphlet was rebound into a book.

Paper Quality

The main body of the book, which includes all of the writing, is printed on thin, speckled, lightly colored pages. The paper is not uniform, indicating that paper pulp was used to create these pages. The printing on the pages is colored black with no variations in color and no embellishments. There is no evidence of marginalia aside from marks that bear the “University of Pennsylvania Library” name on the first few pages with print. The first few pages in both the beginning and end of the book are blank, and are considerably darker, thicker, and less speckled than the rest of the book. The difference in quality between the body of the book and the blank pages in the beginning and end indicate that these blank pages were added later, further bolstering the case that this book was originally printed as a pamphlet and was later rebound by someone who wanted to save it for a longer period.

Binding Characteristics

Regarding the binding of this book, there is a gap between the original binding of the pamphlet and the spine of the book through which the inner working of the book can be seen. It appears that the pamphlet itself was crudely stab-stitched, perhaps to save time or funds, and when the pamphlet was rebound into its current form, it was glued into the spine of the “shell” of the book. This is confirmed by the fact that if the pamphlet were bound directly into the spine of the book, rather than glued, the separation between the paper and the spine would mean that the pages of the pamphlet would be falling out, but the pamphlet in its current state is held together with the stab-stitching even though it is coming apart from the spine, presumably due to the deterioration of the glue holding the binding and pamphlet together.

Printing

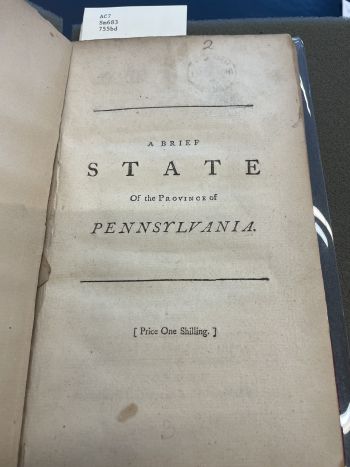

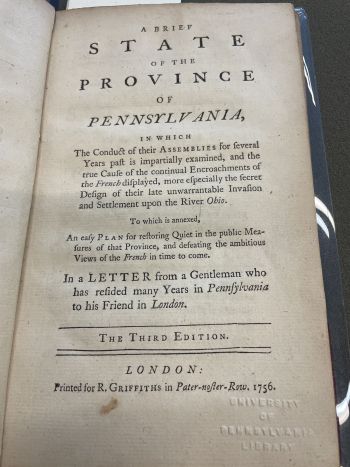

The pamphlet itself has a few interesting markings that help to cement its origin and purpose. On the first printed page, the price of “One Shilling” is printed. This was a common price for fiction books over 100 pages in 1756, but not for short pamphlets totaling 47 pages, which would usually have considerably lower prices. [6] This high price indicates that the pamphlet was intended to be consumed by more affluent and educated individuals. On the next page, where the full title of the book is printed, there is a note that says “London: Printed for R. Griffiths in Pater-noster-Row, 1756.” This note is important for several reasons. First, it confirms that while this pamphlet was written in Pennsylvania by William Smith, it was printed in London. Second, it states the location of publication as Paternoster Row, which was an area in London where many printing houses and publishers were located. Third, it identifies the publisher as Ralph Griffiths, who was a notable publisher who owned a publishing shop in St. Paul’s Churchyard, and afterward in Paternoster Row in London. [7]

Rebinding and Pamphlet Use

It is evident that this pamphlet was rebound into the form of a book as shown by the marbled paper decorations that were not available when the pamphlet was published, the difference in quality between the pamphlet itself and the blank papers in the beginning and end of the book, and the visible stab-stitching of the pamphlet that was seemingly glued into the spine of the book. Additionally, the stab-stitching and thin, speckled, and plain pages suggest that this pamphlet was not made for a decorative purpose, but rather to be distributed quite quickly to a large swath of readers.

Conclusions and Significance

The characteristics of the pamphlet indicate that it was printed for the purpose of mass distribution, which is in concurrence with the overall subject matter of the pamphlet, which was a recent political event that William Smith sought to provide his strong opinion on. The notably expensive price [6] assigned to this pamphlet, along with the fact that the pamphlet was written in Pennsylvania while it was printed and distributed in London, both indicate that this pamphlet was not made for Pennsylvanian readers but was intended for wealthy Londoners. William Smith expressed the opinion often in his pamphlet that the Pennsylvanian Assembly was subverting and purposefully disobeying the authority of the British government [4], and it seems that this pamphlet was intended to create similar feelings of anger in Britons who were in the middle to upper classes of society and were potentially affiliated with the Crown. The inflammatory language used throughout the pamphlet reflects Smith’s potential frustration that the British Government was not chastising the Pennsylvanian Assembly for refusing to contribute to military operations, and his purposeful publication of the pamphlet in London, rather than in Philadelphia, indicates that the pamphlet was intended to circulate amongst high society in England, which may not have direct knowledge of circumstances in colonial Pennsylvania. This lack of direct knowledge provided William Smith to speak about the French and Indian War from his own Loyalist and Anglican perspective and disguise his controversial opinions as an objective retelling of events; as the pamphlet title says itself, Smith believes that he has “impartially examined”[4] the Assembly and revealed the “true cause of the continual encroachments of the French”.[4]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Kutz, Kim. “A Battle in Quaker Pennsylvania: Reading a Document of the French and Indian War.” Penn State University Libraries, April 26, 2021. [1]

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 1. Smith, William, Papers, 1755-1803 [2]

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Denaci, Ruth Ann. “The Penn's Creek Massacre and the Captivity of Marie Le Roy and Barbara Leininger.” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 74, no. 3 (2007): 307–32.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Smith, William. A Brief State of the Province of Pennsylvania: In Which the Conduct of Their Assemblies for Several Years Past Is Impartially Examined, and the True Cause of the Continual Encroachments of the French Displayed, More Especially the Secret Design of Their Late Unwarrantable Invasion and Settlement upon the River Ohio: To Which Is Annexed, an Easy Plan for Restoring Quiet in the Public Measures of That Province, and Defeating the Ambitious Views of the French in Time to Come: In a Letter from a Gentleman Who Has Resided Many Years in Pennsylvania to His Friend in London. London: Printed for R. Griffiths ., 1756.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Wolfe, Richard J., and Sidney E. Berger. Marbled Paper: Its History, Techniques, and Patterns : with Special Reference to the Relationship of Marbling to Bookbinding In Europe and the Western World. Second edition.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Hume, Robert D. “The Value of Money in Eighteenth-Century England.” Huntington Library Quarterly 77, no. 4 (2014): 373–416.

- ↑ Roberts, W. The Book-Hunter In London: Historical and Other Studies of Collectors and Collecting. With Numerous Portraits and Illustrations. Chicago: McClurg, 1895.