"Common Sense", Early Edition - Thomas Paine

Backgroung

Introduction

"Common Sense" by Thomas Paine, published in January 1776, is arguably one of the most influential pamphlets in American history. Its vigorous argument for the American colonies' independence from Great Britain galvanized public opinion like no other work of the period. This entry explores "Common Sense" through a rare preserved example of a 1776 copy of Thomas Paine's "Common Sense", the impact it had on the American Revolution, and its lasting legacy in shaping democratic ideals. This particular copy of "Common Sense" is currently housed at the University of Pennsylvania libraries, a testament to its historical and cultural significance. It was generously donated by Mrs. Angel Stengel [1], reflecting the continued interest in preserving and studying revolutionary-era texts. The history of its ownership prior to this donation remains less clear, adding an element of mystery to its past and underscoring the importance of such donations in academic and public historical collections.

Historical Context and Relevance

"Common Sense," the pivotal pamphlet by Thomas Paine, emerged at a critical juncture in American history, becoming one of the most influential texts in the lead-up to the American Revolution. Its production and publication were timely, coinciding with a growing discontent among the American colonists towards British rule. Thomas Paine, an English-born American political activist and writer, arrived in Philadelphia in November 1774. He brought with him a background in radical and revolutionary ideas, having been influenced by the Enlightenment thinkers of his time. Paine was deeply troubled by the inequalities and injustices observed under British governance. By late 1775, amidst escalating tensions between Britain and its American colonies, Paine began writing "Common Sense."

The pamphlet was written in a span of just a few months. Paine's arguments were clear and persuasive, advocating for complete independence from Britain rather than mere reconciliation. He presented his case in a straightforward manner, appealing not only to the intellectuals but also to ordinary colonists, making the complex political theories accessible to the masses. His pamphlet was also constantly read aloud[2], consumed by people of all backgrounds, from scholars to the illiterate. This was the main allure of "Common sense," it provided a compelling argument to those who were unsure about independence, presenting a strong and clear case that nudged them decisively toward supporting a break from Britain[2]. "Common Sense" was published on January 10, 1776, by Robert Bell in Philadelphia. The timing was critical as it capitalized on the colonists’ rising frustration following the battles of Lexington and Concord and the ongoing siege of Boston. Paine's work mainly argued two things: firstly that the 13 colonies would be better off if they were independent from England, and secondly that they should establish a modern democratic republic (criticizing monarchies)[3].

The pamphlet sold over 100,000 copies in its first months, spreading like wildfire through the colonies and playing a significant role in shaping public opinion[4]. "Common Sense" not only encouraged the common people of the American colonies to support the cause of independence but also influenced key decision-makers in the Continental Congress. As tensions escalated, Paine’s "Common Sense" continued to inspire and mobilize the colonists, setting the stage for the drafting of the Declaration of Independence in July 1776. The impact of Paine’s writing cannot be overstated; it provided the philosophical foundation that guided the revolutionary movement and altered the course of history.

Publication History: Controversy and Consequences

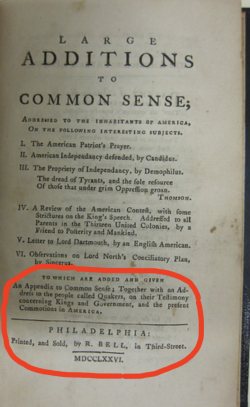

"Common Sense" was published anonymously in Philadelphia under the alias "Englishman," a strategic decision by Paine due to the seditious nature of the text. The pamphlet’s impact was immediate and profound, selling over 100,000 copies in just 3 months (comparable to the sales of a Harry Potter release in modern times), and amounting to around 500,000[4] by the end of the revolution, a staggering number for the period considering the right bearing population of the colonies at the time was around 2 million. Its affordability, at just two shillings, allowed it to spread widely and quickly among the colonies. The choice of Robert Bell as the publisher, a radical printer known for his willingness to take on controversial projects, was crucial in ensuring the pamphlet reached as many readers as possible. Bell's promotional strategies and the broad distribution of the pamphlet played a key role in its success and influence. But as "Common Sense" gained traction Paine and Bell's collaboration would be cut short due to friction between the two. Paine was disappointed after Bell informed him there were no profits (which he intended to donate to the independence movement). Feeling betrayed he immediately cut ties with R. Bell seeking other printers. R. Bell in an attempt to get back at Paine would start printing his own edited copy called, "Large Additions to Common Sense."[5] As the controversy escalated, Bell's actions, driven by a mix of spite and commercial ambition, only served to fuel the public's interest in "Common Sense." His unauthorized edition, featuring additional materials not penned by Paine, aimed to capitalize on the pamphlet's burgeoning popularity. This edition, marketed as being substantially larger due to these "Large Additions," was Bell's attempt to outshine Bradford's authorized version and reclaim his stake in the pamphlet's success. However, Bell's efforts were undermined by Paine's decision not to copyright the work, granting freedom for it to be reprinted by anyone. This allowed for widespread dissemination beyond Bell's control, further democratizing the revolutionary ideas Paine wrote. Despite Bell's initial pivotal role in the distribution of "Common Sense," his relationship with Paine deteriorated irreparably, highlighting a tumultuous chapter in the history of American revolutionary literature. This public dispute not only kept "Common Sense" in the news, increasing its visibility, but also underscored the complexities of publishing in revolutionary times. [5]

Unveiling a Unique Copy of 'Common Sense'

Introduction

This specific copy of "Common Sense" housed at the University of Pennsylvania represents a curious and potentially unique artifact in the history of this revolutionary text. While initially appearing as a typical early edition possibly published by Robert Bell pre-fallout with Thomas Paine, further examination reveals significant deviations that suggest it may be a post-fallout, unauthorized, or even forged edition.

Physical Condition and Material Analysis

- Substrate and Quality: The paper used in this edition is traditional, likely linen rags, consistent with 18th-century printing practices. This book is a codex, its bibliographical format is most likely cuarto due to its size and structure. It is more on the smaller ends of the books with a cover page, introduction, and main bulk of the text following. However, the quality of printing is notably cruder than other known copies published by Bell. There are formatting inconsistencies and typographical errors that are uncharacteristic of Bell's earlier, more carefully produced editions.

- Binding and Structure: The book has been rebound, which is evident from the spine label bearing Thomas Paine’s name—a detail not original to the period when anonymity was crucial for Paine. The rebinding and the presence of a pristine University of Pennsylvania pastedown contrast with the considerable wear and damage observed in the textblock, suggesting a history of significant use and perhaps less careful storage.

- Annotations and Marks of Ownership: The cover page of the book bears the handwritten name "Sam Norton" and the year "1776." This inscription likely represents the owner's assertion of possession and perhaps a demonstration of the book's value to him. Writing one's name on a book was a common practice to claim ownership and prevent theft, and in the context of revolutionary literature like "Common Sense," it might also reflect a personal endorsement of the ideas within. This act of marking can imply the book's importance to its owner and signify its role as a valued object of influence and personal connection during a transformative period in American history.

Printing Anomalies and Authenticity Concerns

- Large Additions and Formatting: Page 44 includes the "Large Additions to Common Sense," indicative of a post-fallout edition attributed to Bell. The nature of these additions and the overall poorer print quality lead to questions about the edition's authenticity. The disparities in formatting and the presence of numerous errors could imply that this is not a genuine Bell edition but rather a pirated version created to capitalize on the pamphlet’s popularity.

- Comparison with Authentic Copies: Contrasts with verified Bell editions reveal significant differences. This copy’s cruder execution suggests it could be the work of a different printer who may have acquired the text and attempted to replicate Bell’s additions without the same level of skill or access to quality printing tools.[1]

Copyright and Licensing Implications

Lack of Copyright: Thomas Paine’s decision not to copyright "Common Sense" was motivated by his desire for widespread dissemination over profit.[6] This edition, regardless of its authenticity, aligns with Paine’s intent in that it represents another vector for the spread of revolutionary ideas. The possible unauthorized nature of this edition highlights the complexities of copyright in the period and illustrates how Paine’s work was subject to interpretations and reproductions that varied widely in fidelity to the original. Paine's back and forth with R.Bell eventually added further spotlight to the already famous pamphlet, even leading to the creation of possible forgeries like the following overall adding to Paine's cause.

Historical and Cultural Significance

- The Challenge of Measuring Impact: The presence of unauthorized or forged editions like this one complicates efforts to fully understand the dissemination and impact of "Common Sense." Forgeries indicate high demand and the persuasive power of Paine’s arguments, yet they also muddy historical records about the pamphlet’s reach and readership. The variation in quality among different editions could affect the reception and interpretation of its content, posing challenges for historians trying to trace its influence accurately.

- Reflections on Authorship and Copyright: The complexities surrounding the copyright, or lack thereof, of "Common Sense" reflect early attitudes toward intellectual property and the sharing of revolutionary ideas. Paine’s decision not to copyright his work facilitated its widespread reproduction, both authorized and unauthorized, which was crucial for the spread of revolutionary sentiments but also led to variations that could dilute or alter the original message.

- Broader Implications for Revolutionary Media: This unique edition highlights the role of print media as a tool for revolution. "Common Sense" not only spread revolutionary ideas but also demonstrated the power of the written word in mobilizing public opinion against tyranny. The existence of variations and forgeries underscores the pamphlet’s ubiquity and the lengths to which individuals would go to access and propagate its content.

Conclusion: The Legacy of "Common Sense"

This examination of a unique edition of "Common Sense" at the University of Pennsylvania underscores the complexities and the enduring influence of this revolutionary text. As a pivotal document in American history, Thomas Paine's pamphlet catalyzed the movement towards independence and showcased the power of print media to shape public opinion and spur societal change. The anomalies in this specific copy—such as the inclusion of "Large Additions" and the apparent crude printing—highlight the frenetic demand for Paine's ideas and the lengths to which publishers went to meet this demand. This edition not only reflects the vibrant print culture of the 18th century but also illustrates how the spread of revolutionary ideas often transcended the constraints of copyright and conventional publication methods.

In essence, "Common Sense" was more than just a pamphlet; it was a manifesto that played a crucial role in transforming simmering colonial unrest into a full-blown revolution. Its widespread dissemination, facilitated by Paine's deliberate avoidance of copyright, ensured that his calls for independence reached a broad audience, significantly impacting the course of American history. This specific edition's journey—marked by physical wear, annotations, and historical context—enriches our understanding of its impact and serves as a reminder of the power of print media to influence political and social landscapes. Through its analysis, we gain deeper insight into the revolutionary era and the instrumental role of "Common Sense" in shaping the destiny of a nation.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Penn Libraries, Common sense : addressed to the inhabitants of America, on the following interesting subjects. I. Of the origin and design of government in general, with concise remarks on the English Constitution. II. Of monarchy and hereditary succession. III. Thoughts on the present state of American affairs. IV. Of the present ability of America, with some miscellaneous reflections / written by an Englishman. ; [Two lines from Thomson]., (UPenn, Libraries),https://franklin.library.upenn.edu/catalog/FRANKLIN_9959205633503681

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 ,Kiger, Patrick. “How Thomas Paine’s ‘common Sense’ Helped Inspire the American Revolution.” History.Com, A&E Television Networks, 28 June 2021, www.history.com/news/thomas-paine-common-sense-revolution.

- ↑ “Thomas Paine’s Common Sense.” Ushistory.Org, Independence Hall Association, www.ushistory.org/us/10f.asp#:~:text=He%20argued%20for%20two%20main,Paine%20avoided%20flowery%20prose. Accessed 5 May 2024.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 NCC Staff. “Thomas Paine: The Original Publishing Viral Superstar.” National Constitution Center – Constitutioncenter.Org, 10 Jan. 2023, constitutioncenter.org/blog/thomas-paine-the-original-publishing-viral-superstar-2#:~:text=Common%20Sense%20sold%20120%2C000%20copies,American%20populations)%20was%202.5%20million.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Mulder, Megan, et al. “Common Sense, by Thomas Paine (1776).” ZSR Library, 10 Oct. 2016, zsr.wfu.edu/2011/common-sense-by-thomas-paine-1776/.

- ↑ History.com editors. “Thomas Paine: Quotes, Summary & Common Sense.” History.Com, A&E Television Networks, 9 Nov. 2009, www.history.com/topics/american-revolution/thomas-paine.