Royal Library Concordance, page 105

View FullscreenWhen the household presented Charles with the King’s Harmony in May 1636, he was greatly pleased with its handiwork – so much so that he reportedly wondered aloud whether they might also make him a concordance of the books of Kings and Chronicles using their novel cut-and-paste method of composition. Thus a new genre of book was born at Little Gidding, the Old Testament concordance.

Little Gidding made three such concordances: the requested book of Kings and Chronicles, made for Charles I around 1637, now at the British Library; a Pentateuch concordance of the five books of Moses presented to Archbishop William Laud in 1640, now in the library of St. John’s College, Oxford; and a second Pentateuch concordance made for Prince Charles in 1642, now in the Royal Library at Windsor. The Prince may have requested his own Pentateuch after seeing Laud’s. A plan for a second book of Kings and Chronicles and a bundle of materials for another Pentateuch concordance are also extant in the Ferrar Papers at Magdalene College, Cambridge. With the exception of the first concordance made for King Charles, all of these books were made after the patriarch Nicholas Ferrar’s death and so prove that the household’s bookwork was not dependent upon his instruction, as earlier scholars often assumed, but in fact was a highly collaborative enterprise.

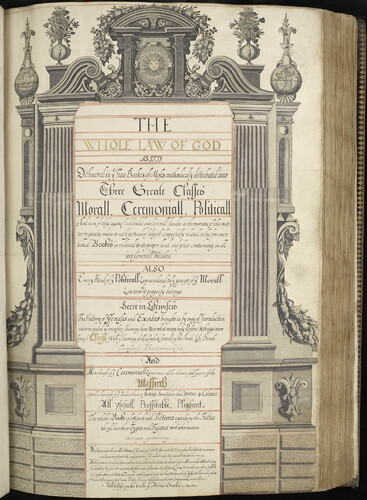

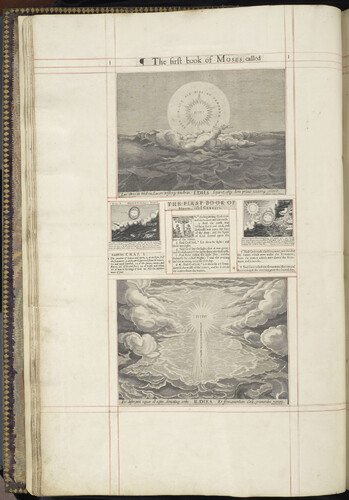

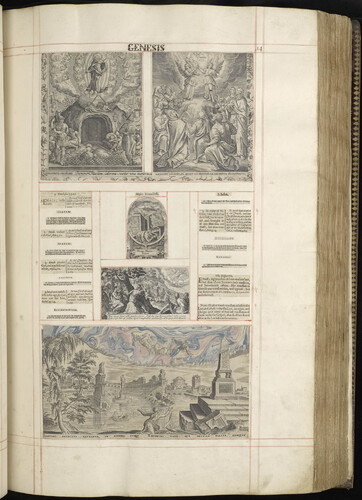

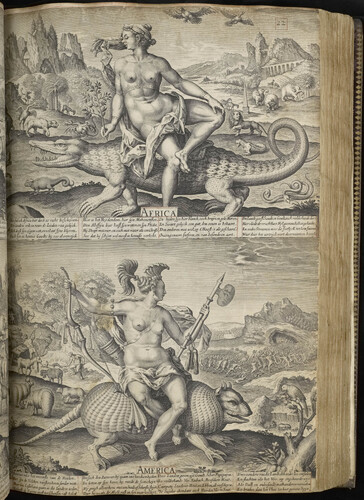

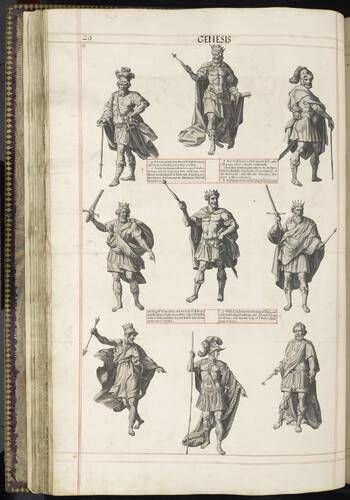

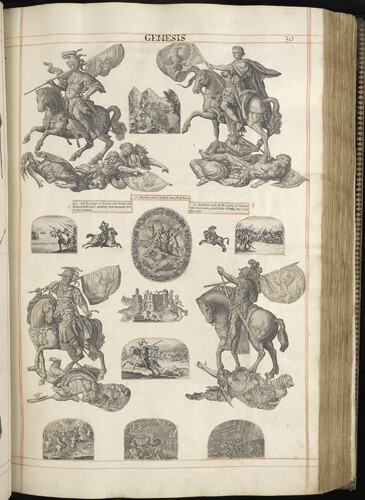

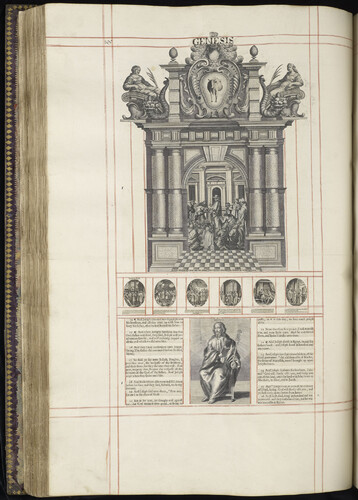

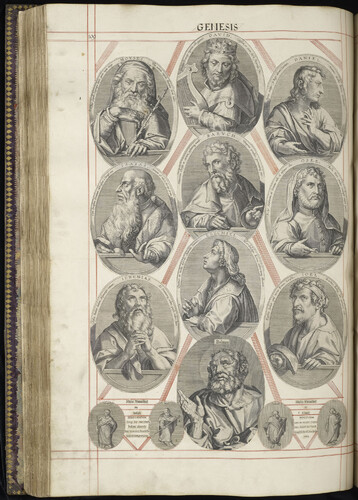

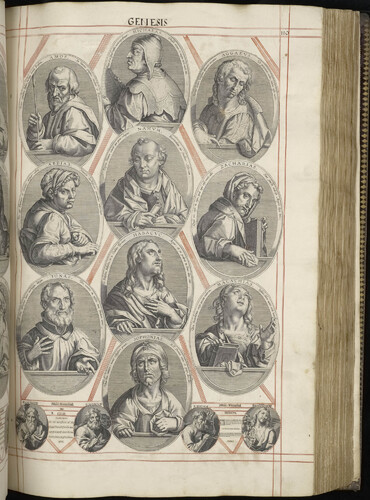

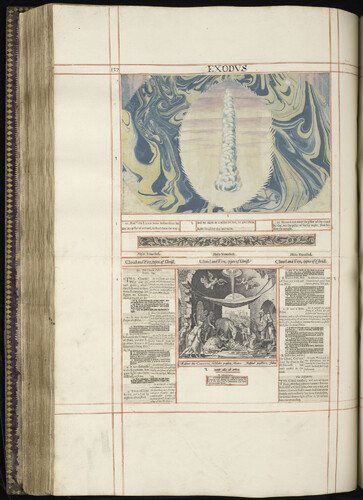

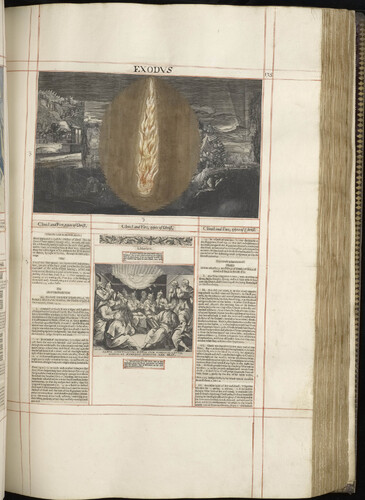

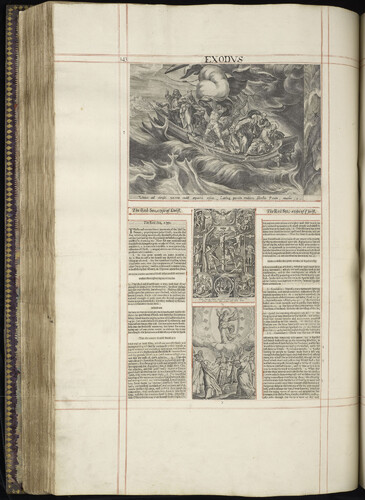

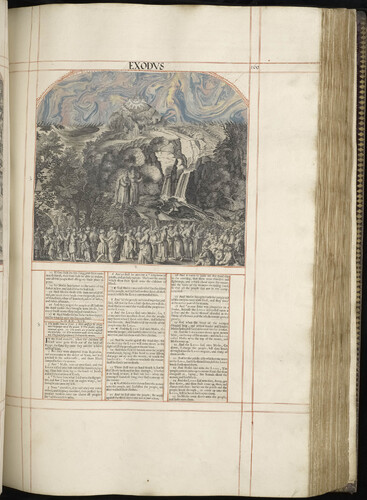

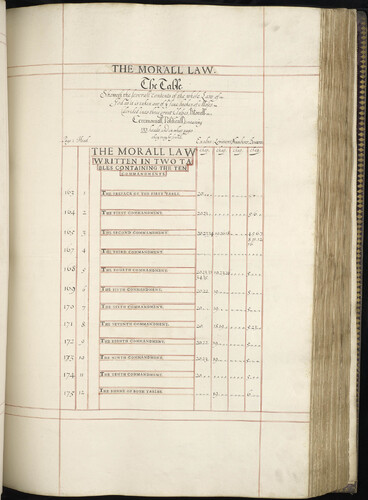

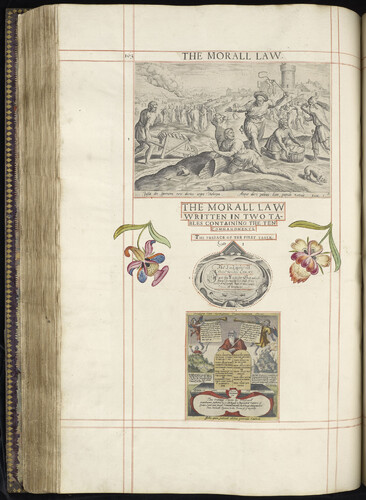

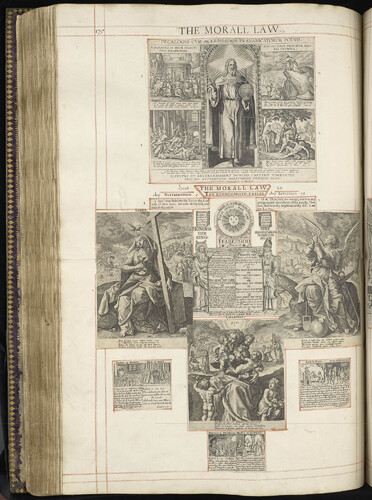

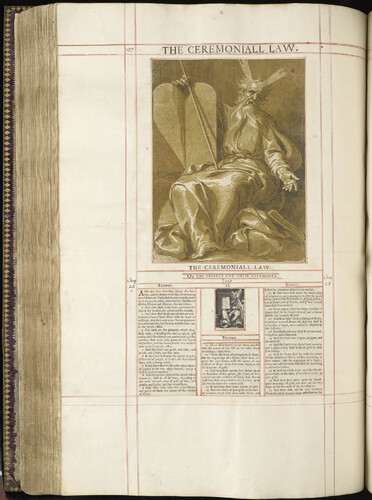

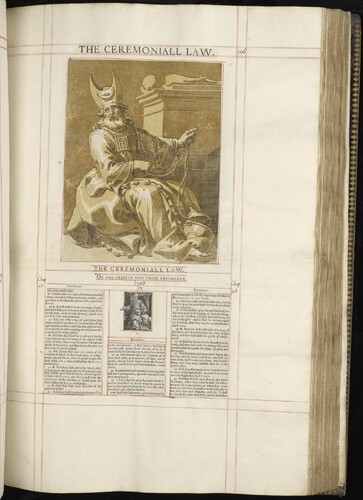

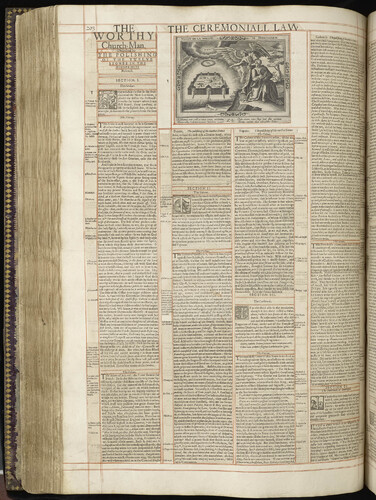

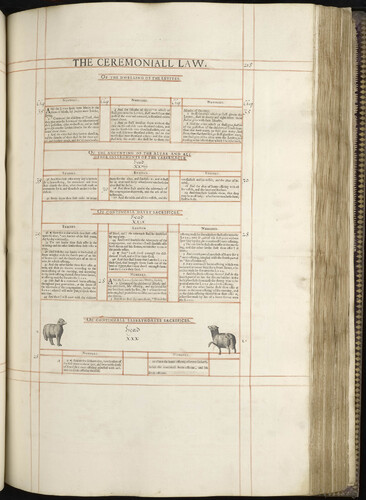

According to the Royal Library, the Pentateuch concordance made for Prince Charles – several images of which are included here – “is the last, largest, and most magnificent volume made by the community.” It is enormous: over two feet tall, with over 450 pages and 1,000 engravings. It weighs more than 52 pounds. Aside from its sheer size, though, it is one of the more complexly assembled concordances. Like the Pentateuch concordance made for Laud, it functions as an index of all the laws of the books of Moses, or the first five books of the Bible. These are divided, in the style of a commonplace book, under the headings of “Moral,” “Ceremonial,” and “Political” law. Excerpts from works on typology, including William Guild’s Moses Unvailed (1620) and Thomas Tailor’s Christ Revealed (1635), are pasted throughout this index. Hand-colored engravings and woodcuts, serrated slices of marbled papers, and exquisitely cut figures also make an appearance in this volume. The variety of texts, page layouts, and imagery attest to the households’ advances in their cut-and-paste-method of composition, their “new kind of printing.” By 1642, the Ferrars and Collets knew the power of this new technology and, more, had the tools and skills to utilize it.

Sadly, Prince Charles never got to enjoy the book himself. He and his father, the King, got a preview of the volume as it was being made in 1642, when they stopped at Little Gidding on their journey northward. (It was 1642, and they were fleeing London in hopes of shoring up support in the more loyal North.) The civil wars that followed prevented Prince Charles from ever receiving the book, and for many years it was hidden behind a false wall in a cupboard in a home near Hatfield. It finally came to the Royal family in 1953, when its then-owners presented it to Queen Elizabeth II.

While the entire volume remains to be digitized, the Royal Library has provided the public with several high-resolution scans and granted permission to the editors to include them in this digital network of Little Gidding harmonies. We include them here, with links to source images when known, to give a sense of the artistry of the household’s later bookwork. More about this book may be discovered at the Royal Library’s website.