Tunnel book depicting a promenade on the Champs-Élysées

Introduction

The University of Pennsylvania’s Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts possesses a colorful, elaborately detailed Victorian-era tunnel book (a type of pop-up book) featuring a three-dimensional layout. This unnamed book, which contains five internal prints with hand-colored etchings and a front and back cover, measures approximately 13 x 19 x 1 cm when closed. It has no author and is cataloged simply as "Tunnel book depicting a promenade on the Champs-Élysées".[1] As the catalog title indicates, this tunnel book depicts people walking along the Champs-Élysées, a world-famous avenue in Paris, France.

The date and location of authorship are not provided; however, the book is thought to have been made during the nineteenth century, but not earlier than 1836, as this is the year when the Arc de Triomphe, which is depicted in the book, was completed after being commissioned by Napoleon Bonaparte thirty years prior to celebrate his victories in war.[2] In the Notes section of the library catalog listing, a comparison is made to a similar 1827 tunnel book depicting an unfinished version of the Arc de Triomphe: Optique No. 4 Promenade de Longchamp (Cf. R. Hyde, Paper Peepshows, cat. 24.)[1] In fact, many nineteenth century tunnel books may have portrayed similar scenes of the Champs-Élysées, differing in details based on the artist and the year created. Historian Ralph Hyde’s book Paper Peepshows: The Jacqueline and Jonathan Gestetner Collection describes Optique No. 4 as depicting “the occasion of the Promenade de Longchamp,” with spectators seated in chairs and looking west toward the Arc de Triomphe, “still lack[ing] its attic storey,” which was added to the monument in 1836.[3]

Due to the popularity of tunnel books in the nineteenth century, it is likely that the Kislak Center tunnel book was created at some point in the mid- to late-1800s, after the Arc de Triomphe was completed. There is no evidence of this book being copyrighted or licensed. It book was acquired by the University of Pennsylvania in 2016, when it was donated by Alan Maxwell Fern (1930) and Lois Fern (1934).[1]

Background

Most modern bound books typically present information in a flat, two-dimensional format. Physical books, however, can take on a wide range of shapes, sizes, and forms, with some having a three-dimensional, interactive design. Over the years, books with three-dimensional pages have been called a variety of names, such as pop-ups, optiques, areaoramas, cosmoramas, peepshows, and tunnel books [4] These books feature images that pop up, fold down, move, rotate, or are arranged in a layered fashion that provides a three-dimensional effect.

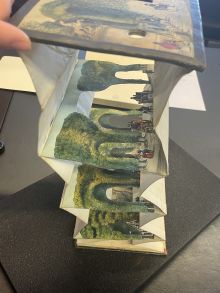

A tunnel book is designed in such a way that the user must actively lift up the cover in order to “read” the book, which often involves looking at pictures rather than reading words. Individual pages are actually detailed cutouts with openings that enable viewers to peer through the pages, all the way to the back of the book. Pages are held together with paper strips that can be folded, allowing the user to open and close the book like an accordian. Openings on the covers (peep holes) invite the viewer to peer inside when the book is pulled open. When looking through these holes and peering at the scene, the user can shift their gaze and viewing angle so that more or different parts of the scene are revealed, making the viewing process more interactive and less static, unlike a piece of two-dimensional art.

In the Victorian era, paper tunnel books featuring colorful, layered scenes that “gave the illusion of depth and motion” became very popular and were mass produced [4]. In her 2002 article for Journal of Design History, scholar and researcher Amy Ogata describes nineteenth-century peepshow books as being common and inexpensive (“if not cheap”), and typically made of “flexible folding paper or linen bellows with lithographed or engraved, and often hand-colored, scenes paced in succession to give the visual effect of receding space."[5]

Structure and Content

The antique tunnel book at the Kislak Center is structured in a manner similar to Victorian-era peepshow books. The front and back covers are pasteboards with prints glued on top; the front cover has three viewing holes and the back cover has one. Individual pages are made of paper and have the prints (etchings colored by hand) directly on the page. Paper strips hold the pages together and enable the book to be opened and closed like an accordian. When opened, the book expands from 1 cm to approximately 51 cm. There is no evidence of marginalia, other than what appears to be a handwritten (and difficult to discern) name on the back of the front cover. Because tunnel books are not like traditional books with words and margins, notes or comments would seem to be unnecessary and take away from their beauty or use as souvenirs, toys, or pieces of art.

One of the pages features a full-page print on both sides of the leaf; however, on the rest of the pages, each print is not a full page but is instead a cutout, carefully designed to display the scene when one pulls the book open, holds it out, and looks into one of three different viewing holes on the front cover or one on the back cover. The middle opening on the front cover is a slightly larger square hole that directs the viewer to the Arc de Triomphe at the end of the Champs-Élysées, while two slightly smaller circular holes to the left and right display the scene from slightly different perspectives. If we look over the top of the front cover, we can see that every page is a part of the scene. If we look over the top of the back cover, we can still see a scene, but we are viewing only one side of the leaf with the full-page print. The pages with detailed cutouts are solely for the view from the front cover, as they help to create a feeling of depth and dimension.

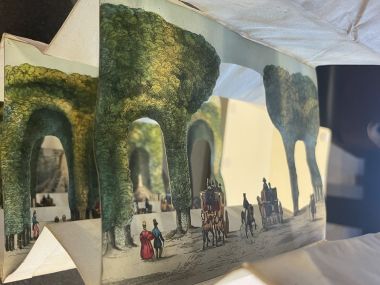

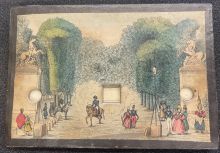

As mentioned earlier, this tunnel book portrays a promenade on the Champs-Élysées in Paris. The scene depicts men, women, and children of varying ages, all in Victorian-era clothing, such as dresses, bonnets, waistcoats, and top hats. Some people are walking while others are on horseback or riding in horse-drawn carriages on the tree-lined avenue. Along with people, trees feature prominently in the images. The trees are a rich green color, indicating a spring or summer scene. The use of bright color is evident throughout the book in each of the different etchings and is especially well-preserved on the covers. Upon peering into the holes on the front cover of the book, the viewer can see crowds of people strolling down the avenue, perhaps on their way to the Arc de Triomphe, which we can see at the very end of the book. The front cover features the Chevaux de Marly, which are sculptures of horses atop tall pedestals on either side of the avenue’s entrance, while the back cover shows people in a park, perhaps the Place e la Porte Maillot, as noted in the library catalog.[1]

Even though there is no author listed for the book, it is possible that the artist who created and painted the etchings was also the one who formatted the book and put all of the pieces together, as the act of creating such a book would require significant attention to detail as to how the book would be used and seen by the viewer. In his book Paper Peepshows, Ralph Hyde notes that several copies of Optique No. 4 Promenade de Longchamp (which closely resembles the Kislak Center tunnel book) have vendor labels indicating that they were produced in Paris.[3] Based on this information, it is possible that the Kislak Center tunnel book was also made in Paris. Hyde also notes that for unnumbered French paper peepshows (or optiques), he has only seen one maker’s name, and has speculated whether this maker may have been responsible for the majority of the unnumbered French optiques.[3]

-

A view of one of the tunnel book’s full-page prints showing the Arc de Triomphe.

-

A view of one of the tunnel book’s pages with detailed cutouts, which gives a feeling of depth.

-

A view of a cutout page showing colorful details. Note the folded paper strips (or bellows).

-

A view of the tunnel book’s images as seen through one of the front-cover peepholes.

Comparison to Optique No. 4 Promenade de Longchamp

The Kislak Center tunnel book and Optique No. 4 Promenade de Longchamp, as described in Paper Peepshows, bear many similarities as well as a few differences. Both books are about the same size (with the Kislak book being slightly larger) and feature a similar number of cutout panels with hand-colored etchings depicting the same Promenade de Longchamp scene. The front covers are nearly identical, yet upon closer inspection, we see a few differences. Optique No. 4 has only one circular viewing hole, as opposed to three on the Kislak book, and while the placement of the horse statues, trees, and people is roughly the same, Optique No. 4 is lacking some figures. For example, a military figure on horseback that is placed prominently on the center of the Kislak book cover is absent on Optique No. 4, and in front of the left pedestal, instead of woman and child, we see a man and a woman. Additionally, and as mentioned previously, Optique No. 4 does not show the Arc de Triomphe in its completed state.

While some of these differences may reflect artistic choices, it is possible that many versions of this particular tunnel book were produced over the years, as the Champs-Élysées was extremely popular. It became known as “a very fashionable spot” in the nineteenth century, serving not only as the setting for the Promenade de Longchamp and other festivals, but also as the site for some of the first world fairs, including the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1855.[6] In his book Illusions in Motion, media archaeologist Erkki Huhtamo explains that in the early 1800s, miniature roll panoramas also featured hand-colored illustrations of the Champs-Elysées and other famous European streets.[7] Hyde points out that Optique No. 4 (and its many versions) represents “the first in another category of peepshow—customs.”[3] In this case, the custom is the Parisian tradition of the Promenade de Longchamp: a social event taking place each year during Holy Week at the Bois-de-Boulogne and the Champs-Élysées. Originally a religious pilgrimage, it soon became a “secular spectacle” that was popular prior to the French Revolution and later revived in the nineteenth century.[8] “Participants were there to see and be seen,” according to the J. Willard Marriott Library’s Rare Book Department, which also possesses a tunnel book called Promenade de Longchamp Optique No. 4, but which is dated ca. 1810.[8] Although there was a divide between the rich and poor in Paris at this time, this event became so socially popular that it brought people together.

The tunnel book in the Kislak Center offers a vivid representation of this Parisian custom, with large crowds of people of all ages gathered on the bustling avenue. Understanding events like the Promenade de Longchamp sheds light on why this occasion may have been the subject of Victorian-era tunnel books. Such a large, celebratory social gathering in the heart of Paris would indeed be the type of event that people would want to record in the form of pictures as a way to commemorate the occasion. Because nineteenth century paper tunnel books were inexpensive, they could be produced in large numbers and sold as souvenirs, thus making them both ephemeral and collectible objects that captured an important moment in time, such as with the colorful promenades that took place each spring on the Champs-Élysées. As such, they would appeal to tourists, travelers, and children alike.

History of Tunnel Books

Raree boxes and the emergence of paper peepshows and tunnel books

In the mid-eighteenth century, peepshows were first made by Martin Engelbrecht in Augsburg, Germanyy, and became especially popular in Europe in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[3] Early forms were not books at all, but rather large boxes with holes on one side that allowed viewers to peer or “peep” in at images painted on panels that were placed inside the box and illuminated from light entering the box.[5] These peepshow boxes were also referred to as raree boxes or “wonder boxes.”[9] At traveling peepshows or raree shows, the raree man would charge people a small fee to peer inside the box while “bringing the scene to life” through storytelling.[10] Peepshows depicted a wide variety of scenes, from landscapes and popular cities to exciting spectacles and historically important events, monuments, and landmarks. Peepshows were not confined to northern Europe, but spread to countries throughout the world, with exhibitions taking place in North Africa, Western Asia, Southeastern Europe, India, China, Japan, and the United States.[7] Erkki Huhtamo states, “the form seems to have originated in Europe and spread elsewhere along trade routes, and in the wake of imperialistic expeditions."[7] While raree men displayed their peepshow boxes, which often contained multiple different images, to large audiences, individuals were able to possess their own smaller peepshow devices for entertainment.[5]

Paper peepshows were first introduced in the 1820s, specifically in Paris, London, and Vienna.[3] Into the nineteenth century, the larger peepshow apparatus began to take various smaller forms, such as the polyorama panoptique (a wooden box with paper bellows), peep eggs (made of alabaster), and tiny panoramas.[5] These forms gave rise to what we now call peepshow or tunnel books. These books, usually made of paper, were inexpensive and portable, making them easier to possess and transport. Paper peepshows often depicted tunnels, bridges, monuments, festivals, and events through colorful cutouts arranged in such a way that peering through the viewing holes gave a person the experience of visiting the place being shown. Such three-dimensional books offered the viewer an opportunity to see a particular place, event, or cultural practice in a uniquely engaging way. These might include Chinese weddings, Turkish feasts, British coronations, French horse races, structures like the Suez Canal or Thames Tunnel, or international expositions.[4]

Common themes, use as souvenirs, and historical significance

These whimsical books were seen as “optical entertainment” for both children and adults alike due to their captivating details, even though some of these details were later found to be factually inaccurate.[3] This did not seem to detract from their appeal. According to the Victoria and Albert Museum, optical devices “were all the rage” in the mid-nineteenth century.[10]. Paper peepshows became sought after keepsakes commemorating national achievements as well as international expositions. Some of the most popular paper peepshows depicted the Thames Tunnel and the Great Exhibition of 1851, which featured the elaborate Crystal Palace. The public was fascinated by the tunnel—considered a feat of modern engineering—as well as the expo, and both led to the creation of a wide range of souvenirs and collectibles, including tunnel books.

Unlike two-dimensional picture books, these three-dimensional interactive objects allowed the viewer to immerse themselves in the spectacle. Ogata states, “The experience of looking into a device that held a magical world in miniature opened up possibilities for apprehending both the physical aspects of the natural world and the power of the imagination.”[5] Reflecting on the power of miniaturization, Huhtamo explains that we should not underestimate the impact of small, ephemeral objects that can we touch, hold in our hands, and become familiar with, as they can provide a much more intimate way of understanding something, as opposed to a larger, “untouchable” format.[7]

According to Ogata, tunnel book peepholes often “approximated the perspective of a visitor to the exhibition,” so they not only served as keepsakes, but also allowed viewers to “relive the visual experience of the exhibition.”[5] As such, Ogata believes these objects took the concept of phantasmagoric illusion (whereby optical illusions and visual tricks create dreamlike representations of physical objects) and made it something real “for popular consumption and collective memory."[5] Because tunnel books present a particular place captured in a moment of time, there is a sense of privatization, as the viewer peering into the book gets their own personal look at something, as if they are there in the moment, just like the other spectators depicted in the artwork. However, the peepshow by nature is an illusory experience for the viewer. Even though it may be depicting an actual place or event, the way in which the pages are aligned creates a dreamlike experience.

Readership

Because Victorian-era paper peepshows/tunnel books were able to “convey a sense of wonder, of depth, of looking at something in a new way,” they appealed to people of all ages.[11] Despite often being categorized as toys, their intended audience was initially everyone, not just children. Indeed, historians have noted that peepshow boxes and books were enjoyed by both adults and youth. Part of their appeal was that the experience of peering into these devices was a personal one. A viewer could feel like they were experiencing the excitement of a world fair, an exotic location, or a marvel of modern technology from the comfort of their own home.

With the Kislak Center’s "Tunnel book depicting a promenade on the Champs-Élysées," the viewer—young or old—could imagine themselves strolling down the crowded avenue with friends and family and enjoying a day of people watching. We can speculate that this book’s readership most likely included people from a wide range of ages, as the illustrations feature mostly adult figures. Readership most likely included Parisians and people from other European cities and towns, perhaps locations that were already familiar with the Champs-Élysées and the Promenade de Longchamp. Because there were likely many versions and copies of this tunnel book, which were not expensive to produce, it most likely was circulated as a type of souvenir.

With the advancement of photographic technology, people found new ways to experience the world. The tunnel book audience shifted as different mediums offered more realistic visions of places and events. As the desire for realistic photographs increased, tunnel books became less valued as a novelty for adults and were considered to be more suitable as a form of children’s entertainment.[5]

Despite paper peepshows diminishing in popularity for adults, they continued to evoke a sense of wonder and evolved into different types of imaginative books for children. In Interactive Books: Playful Media Before Pop-ups, author and researcher Jacqueline Reid-Walsh states that advances in paper engineering led the development of new forms of three-dimensional children’s books—interactive books with moveable parts as well as pop-up books with innovative folded designs that did not require tabs or pulls to create a multidimensional experience.[12] Some of the design elements were borrowed from stationary peepshows and tunnel books. For example, Reid-Walsh says the arrangement of layered cutouts, similar to paper peepshows, could give the appearance of a miniature stage, creating “a complex theatrical viewing experience” for the child.[12] Movable theater books for children, which were first published around 1860, are thought to have originated from traveling peepshow boxes and later, paper tunnel books, continuing the tradition of three-dimensional storytelling.[13]

Victoria and Albert Museum Collection

There is an extensive collection of tunnel and peepshow books at the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London, England. More than 350 of these books were gifted to the museum from collectors Jacqueline and Jonathan Gestetner.[4] The Gestetner’s had possessed the world’s largest collection of 19th-century peepshow books prior to donating them to the museum, which digitized the books to ensure that they can be viewed by the public without being damaged, as many are very fragile[14]. The peepshows in this collection feature a wide range of scenes from Victorian life as well as faraway places and famous events. V&A curator Catherine Yvard, as interviewed by The Guardian in 2016, stated that the books in this collection “offer wonderful insights into social history. Considering that most of them would have been made quite cheaply, it is a miracle that so many have survived”.[14] The collection includes numerous books devoted to the Thames Tunnel and the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, London. In addition to 19th century paper tunnel books, the museum has a few solidly built peepshow boxes that are considered to be precursors to the tunnel books. Two of these are 18th century pieces called “perspective views,” created by German engraver Martin Engelbrecht and featuring vocational scenes, such as a painter’s studio and printing workshop.[10] Additionally, the Gestetner collection contains a piece that is considered one of the oldest tunnel books ever created: a peepshow by H. F. Muller showing a country house and garden, dating back to 1825.[14] After gifting their collection of tunnel books to the V&A, the Gestetner’s commissioned Ralph Hyde to write his book Paper Peepshows.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 tunnel Book Depicting a Promenade On the Champs-Élysées [Place not identified: publisher not identified, n183. https://franklin.library.upenn.edu/catalog/FRANKLIN_9977262814403681

- ↑ Murray, Lorraine. “Arc de Triomphe." Encyclopedia Britannica, 24 Mar. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Arc-de-Triomphe. Accessed 13 April 2023.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Hyde, Ralph, and Erkki Huhtamo. Paper Peepshows : the Jaqueline & Jonathan Gestetner Collection / Ralph Hyde.Woodbridge, Suffolk, England: Antique Collectors' Club, 2015.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Khan, Eve. “Antiquarian Book Fair Offers Victorian Children’s Peep Shows.” New York Times, 2 Apr. 2015. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/03/arts/design/antiquarian-book-fair-offers-victorian-childrens-peep-shows.html?smid=url-share. Accessed 3 Apr. 2023.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 Ogata, Amy F. “Viewing Souvenirs: Peepshows and the International Expositions.” Journal of Design History, vol. 15, no. 2, 2002, pp. 69-82, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3527199. Accessed 3 Apr. 2023.

- ↑ Marsh, Janine. “The History of the Champs-Élysées Paris.” The Good Life France, https://thegoodlifefrance.com/history-the-champs-elysees-paris/. Accessed 14 Apr. 2023.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Huhtamo, Erkki. Illusions in Motion: Media Archaeology of the Moving Panorama and Related Spectacles. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2013.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Rarebooks (J. Willard Marriott Library). “Book of the Week — Promenade de Longchamp, Optique no. 4.” Open Book — News from the Rare Books Department of Special Collections at the J. Willard Marriott Library, The University of Utah, 28 March 2018, https://openbook.lib.utah.edu/book-of-the-week-promenade-de-longchamp-optique-no-4/. Accessed 12 Apr. 2023.

- ↑ Lidington, Tony, et al. “Peepshows: New Perspectives, Moves and Media.” The Magic Lantern, no. 8, Sept. 2016. https://www.magiclantern.org.uk/the-magic-lantern/pdfs/4010062a.pdf. Accessed 3 Apr. 2023.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Victoria and Albert Museum. “Paper peepshows.” V&A, https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/paper-peepshows Accessed 12 Apr. 2023.

- ↑ “An Inside Look at Three Centuries of Tunnel Books.” YouTube, uploaded by UFlibraries, 19 Mar. 2021, https://youtu.be/z46xUTOKz64. Accessed 3 Apr. 2023.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Reid-Walsh, Jacqueline. Interactive Books : Playful Media Before Pop-ups. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2018.

- ↑ Sarlatto, Mara. “Paper engineers and mechanical devices of movable books of the 19th and 20th centuries.” Italian Journal of Library, Archives and Information Science, vol. 7., no. 1, 2016, DOI:10.4403/jlis.it-11610. Accessed 28 Apr. 2023.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Daley, Jason. “This Museum’s Giant Collection of Paper Peepshows Offers a Pinhole into the Past.” Smithsonian Magazine, 8 Aug. 2016, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/museums-giant-collection-of-paper-peepshow-offers-pinhole-into-past-180960012/. Accessed 3 Apr. 2023.