John Gay's Polly (1729)

Introduction

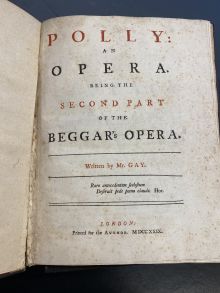

John Gay’s 1729 edition of Polly was the sequel to Gay’s more well-known opera, The Beggar’s Opera. Published in 1729 in London, hot off the heels of The Beggar’s Opera, Polly, and Gay himself, were the subject of controversy and public excitement given the deviant and scandalous content of Gay’s writing. This printing of Polly was acquired by Penn sometime between the late 20th and early 21st century and is currently cataloged as EC7 G2524 729p in the Rare Book Collection of the Kislak Center for Special Collections at the University of Pennsylvania.

Background

John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera was produced on stage in London in 1728 as a satirical ballad opera discussing complex, but controversial, themes such as moral corruption, capitalism, and inequality. Gay’s opera combined “high and low art” by using the medium of the opera to discuss themes not typically deemed proper in high-brow society circles. [1] It was generally accepted that Gay’s opera was a critique of Sir Robert Walpole’s administration. Eventually, upon hearing that Gay had written a sequel to the The Beggar’s Opera, titled Polly, Sir Walpole banned the opera from being performed even after Gay went to great lengths to provide him with a copy for his pre-approval. [2]

Gay’s three-page preface at the beginning of this print edition of Polly reveals much about the controversy surrounding Polly’s antecedent The Beggar’s Opera and allows Gay to reveal his intentions behind printing Polly. It is important to note that the inclusion of this preface allowed Gay to “break the fourth wall” so to speak and communicate his sentiments regarding the banning of his work from the public performance and his hopes for Polly. A sense of authorship and ownership are brought to the page through this preface—two themes that become central to the analysis of Polly as a text and an artifact of popular culture.

Self-Printing in the Eighteenth Century

The imprint page reveals that this edition of Polly was “printed for the author” a term that reveals much about the status of authorship and ownership in 18th-century printing culture. The actual printer of this edition of Polly was William Bowyer, a printer who was a partner of his father’s printing business. [1] The Bowyers typically published scientific works of significance, political pamphlets, and advertising bills. While the Bowyers took charge of the literal printing of Polly, Gay was financially and legally responsible for the production of Polly as a public work. [3] Gay’s experience in publishing Polly highlights the challenge of distinguishing between the functions of bookseller, printer, and publisher in the 18th century. The eighteenth-century English book trade was dramatically different from what we know of as the market for books today. [3] In the 18th century, it was the author’s prerogative to take his work to print and assume all responsibility for defending one’s right to copy through their own means even with the existence of the Copyright Act. [3] This analysis aligns with Gay’s decision to take Polly to the press himself. This edition of Polly was “published for the author” meaning that he was financially responsible for the printing and publishing of this book. [3] Furthermore, he was socially responsible for its circulation, effectively taking on any potential backlash from the Lord Chamberlain following his statement of disdain for Gay’s previous works.

Interestingly the imprint page offers some insight into the political or social tension surrounding a printed work. Typically a complete imprint included place of publication, name of printer, copyright-holding bookseller, and the publisher responsible for distributing or selling the text. [3] In this edition of Polly only the place of publication, ‘London’, can be found on the imprint page and indicates that it was “published for the author” meaning that John Gay was himself responsible for the publishing of the text.

At this point Gay had the money, his name, and social excitement behind him as he sought to publish Polly. [1] The Beggar’s Opera had made him a following on the arts scene, guaranteeing success or at least anticipation for his future works. The production of the opera itself made him a healthy sum of money with which he could invest in printing Polly. [1] Furthermore, the Lord Chamberlain’s ban on Polly’s performance allowed Gay to direct any money he would have invested into Polly’s production into printing and publishing costs.

Piracy & The Statute of Anne

Once an author published their work they were vulnerable to illicit pirating of their texts despite the passage of the Statute of Anne. [4] It seems that given the notoriety and anticipation of Polly following the Lord Chamberlain’s performance ban, some number of booksellers pirated it. In response to the pirating of Polly in the early years, Gay put an advertisement in The Daily Post on April 11, 1729, not a month after his publishing, proclaiming that these pirated editions and their booksellers were under prosecution. [1] The eventual injunction awarded to Gay listed 16 printers and booksellers. [1]

Writers and authors did not rely heavily on the Statute of Anne to protect their works from being pirated. [4] Rather they sought other means. Gay seemed to have even partnered with some of the pirates in an attempt to reclaim at least a portion of his lost profits. As noted, Gay published Polly with his own funds, choosing to publish a quarto volume with 31 copper plates of music. His printer, William Boyer printed 10,500 copies. [1] Only a week after the book allegedly was put up for sale on April 3, 1729, Gay had begun advertising in public press that his book had been pirated and injunctions had been imposed through the courts accordingly. [1] Fascinatingly some of the cheapest pirated copies seem to have been produced within a four-day period—a shocking feat, reflective of London’s printing capacities at this time. [1] The author notes that at least 21 London booksellers were engaged in the pirating of Polly.

However, despite Gay’s claims in the newspapers, the Court of Chancery had not followed through on the injunction until June 12th of that year, and really Gay hadn’t even filed for the injunction until June 3rd. [1] Gay’s actions lead us to question why he first turned to public announcements via ephemeral newspapers rather than a more permanent solution via the courts. The answer lies in a greater trend by authors who saw the provisions from the Statute of Anne as an inadequate way to protect their work.

One might also note that Gay’s public dealings regarding piracy might have added to the allure for potential readers—surely an opera banned by the Lord Chamberlain and widely circulated via piracy must’ve been worth the read. As the saying goes, all press is good press, and in this case, Gay’s announcement in the papers was certainly, and literally, press. John Gay’s actions regarding matters of copyright indicate the limited impact of the Copyright Act of 1709 or the successive Statute of Anne in 1710. [4] The Copyright Act and Statute of Anne were largely ineffective because they required that authors register their works with the Stationers’ Register in order to have their works protected against copyright infringement. [4] Even if a writer were to register their works, the punishments sought by the Court of Chancery were suboptimal and ineffective because they did little to recover their loss in revenue. [4]

Gay seems to find himself in a unique position because the printing of Polly was the only avenue through which this opera circulated for public consumption, there was to be no staging of the show. Thus, his revenue from Polly was entirely dependent on his ability to publish in print and profit from his work. Authors of the 18th century had a distinctly different relationship to copyright and ownership, relinquishing any sense of ownership once their works had been sold to booksellers. The relationship authors had with their work was markedly different from what we conceptualize as author ownership and copyright in the modern era.

Material Analysis and Music Printing

Material Analysis

In a correspondence with Jonathan Swift, Gay described the format and production of the book as follows: “The play is now almost printed, with the music, words, and basses, engraved on thirty-one copperplates…I print the book at my own expense, in quarto, which is to be sold for six shillings, with the music.” [5]

This printed edition of Polly includes both the written text of the play as well as the accompanying music. Given that Gay was unable to stage Polly during his lifetime, printing Polly was an opportunity to provide consumers with both the written text as well as the musical sheets that would have accompanied the play on stage. The book thus functions as two books contained within the format of one.

The book in its entirety includes navigational mechanisms like page numbers and folio labeling that would have assisted the printer in organizing the pages in order. As pictured on the right, the text of the opera has its own separate page numbering and once a reader reaches the second half of the book that includes the music, the page numbering begins anew.

The substrate of the book is standard for mid-18th-century printing. The book is a codex in quarto format; its pages are laid on paper, bound in leather, with gold illumination on the cover. This edition of Polly was well cared for with some exceptions in the binding. The book was rebound at some point with new flyleaves that we believe have 19th-century marbling. Given the presence of margin space we believe that the book was likely only rebound once.

Musical Printing

The process for printing text versus printing music was quite different; although technologies for printed texts were progressing quite rapidly after the introduction of moveable type, music sheets required much finer attention to detail. To produce music by hand one had to write the notes, and if the songs included lyrics, such texts needed to be accounted for as well. Musical printing progressed slightly behind, but parallel to the printing of texts. Following the rise of moveable type, musical printers attempted to utilize this technology through the early 18th century but found themself with unsatisfying results. [6] Musical printers instead preferred to use freehand engraving techniques to produce printed sheet music up until the end of the 18th century. [6]

As noted by Gay in his correspondence with John Swift, the sheet music as composed by Johann Christoph Pepusch and included in the printing of Polly was produced by engraving the music on copper plates. The process known as intaglio progressed roughly as follows: engraving text or music into the plate backward, covering the plate in ink, allowing the ink to pool in the engravings, wiping the plate clean leaving only the engravings inked, and then using a press to transfer the ink from the plate to paper using pressure and suction. [6] This process would have been highly-detail oriented and time-consuming, but one must remember the importance of this work to Gay and the lengths he would have gone to in order to immortalize Polly.

Readership and Provenance

Prior to The University of Pennsylvania’s acquisition of this edition of Polly, the most recent owner was Henry H. Bonnell. Bonnell was a University of Pennsylvania alumni and prominent book collector who had a particular interest in the Brontë sisters. It is fascinating to think why or how editions of Polly might have found their way into collections alongside authors like the Brontës. While John Gay was certainly known for his work during the period in which The Beggar’s Opera was staged, in our modern era his works are not as widely known or even consumed. Nonetheless, The Beggar’s Opera and Polly are immortalized in text as artifacts of popular culture. Polly alone tells its own fascinating story surrounding its publishing. After understanding the context of Polly’s printing one might ask what kinds of consumers were reading the first copies of Polly or preserving them in the decades and centuries that followed. In fact, the previous owner before Henry H. Bonnell can be deduced from the bookplate pictured on the right.

Alice Kuhling previously owned this edition of Polly sometime in 1905. Her bookplate can be found inside the book on the front pastedown page. We know she must have either been responsible for commissioning a rebinding of the book or she acquired it after it was rebound given that her bookplate can be found on the marbled pastedown. When thinking of the readership of Polly, Alice Kuhling’s bookplate provides some insight. Bookplates helped identify the owner of a book but they also captured the personality or literary interests of the reader themselves. [7] Many bookplates depict shelves or stacks of books in which one can actually make out the titles of the books on the spines. This level of detail was intentional and when readers commissioned their bookplate they likely requested that particular titles be made visible. Kuhling’s bookplate includes author surnames like Dante and Byron. Often bookplates were a signaling tool for intelligence and extensive reading. [7] Ultimately, the presence of Kuhling’s bookplate on the first edition of Polly reflects the status of this book as a notable artifact of popular culture.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 Sutherland, James R. "‘Polly’ among the Pirates." The Modern Language Review 37, no. 3 (1942): 291–303. Accessed April 11, 2023.

- ↑ Gay, John, Polly: an Opera: Being the Second Part of The Beggar's Opera. London: Printed for the author, 1729.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Downie, J.A. "Printing for the Author in the Long Eighteenth Century." Essays and Studies 66 (2013): 1-24. Boydell & Brewer Inc.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Suarez, Michael F., S.J. "To What Degree Did the Statute of Anne (8 Anne, c.19, [1709]) Affect Commercial Practices of the Book Trade in Eighteenth-Century England? Some Provisional Answers About Copyright, Chiefly from Bibliography and Book History." In Studies in Bibliography and Booklore V, edited by Michael F. Suarez, S.J., 67-88. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2013.

- ↑ Correspondence of Jonathan Swift, ed. by Harold Williams, 5 vols (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1963‒64), pp. 11, 215 (30 August 1716).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 "Printing Processes." Parlorsongs. Accessed April 30, 2023. http://parlorsongs.com/insearch/printing/printing.php

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 O'Hagan, Lauren Alex. "Shelfies as Identity Performances in Edwardian Britain." BAVS News, August 2, 2021. https://bavs.ac.uk/news/shelfies-as-identity-performances-in-edwardian-britain/