Footnotes

There are many different types of notes, including endnote, footnotes, and margin notes; each type note can serve a different purpose and has different advantages and disadvantages. An endnote is a note that appears at the end of a work and is organized sequentially in relation to where in the work the reference appears. While endnotes do not disrupt the reader or the layout of the page, the reader must flip or scroll to the end of the work in order to see the corresponding note. A footnote is a note placed at the bottom of the page corresponding to the item cited in the text above.[1] Footnotes are beneficial because the notes are easily located on the same page the reader is already looking at. However, this causes a major disadvantage: footnotes can clutter a page and negatively impact the visual. In many cases, footnotes may take up over half of the page.

Margin notes are similar to footnotes in that the note also appears on the same page as the text being cited; however, margin notes appear in the margin of the page in a location corresponding to the point of the text cited. While margin notes are easier to follow than footnotes, they may waste much more physical space on the paper and change the layout of the page much more drastically. Footnotes are usually flagged by numbers in square brackets or superscript or symbols. Traditionally, the order of symbols went: asterisk (*), dagger (†), double dagger (‡), section sign (§), pipe (‖), pilcrow (¶), and, finally, manicule (☞).[2]

History & Uses

In the context of history and academia, the footnote is used to both identify both the primary source and proves that the historian or academic has examined all relevant sources and constructed a new argument based on them. Leopold von Ranke, a 19th-century German historian, championed the idea of citations: footnotes must be used for primary documents to say explicitly what happened. He is considered to be by many the founder of modern historiography. [3] Before his time, historians would have inserted personal opinions and referenced unreliable secondary sources in the footnotes of their work. Von Ranke insisted that that every narrative about the past must rest on systematic analyses of the sources; in short arguments must be supported by tangible evidence, which was a revolutionary idea at the time. [4]

Footnotes and endnotes may be called upon for a variety of different uses, and different disciplines often have different guidelines for their use. The government website for NASA lays out in its footnote guidelines that footnotes should be used in instances such as to acknowledge intellectual debts or indication of the source of information, need it be referenced. Footnotes can also be used to clarify the author’s arguments from that of another writer.[5] Other government offices may provide their own footnote guidelines.[6]

Harper & Brothers Revised Old Testament

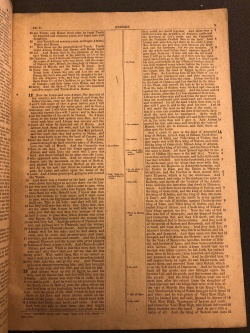

Harper’s Franklin Square Library’s Revised version of the Old Testament (Lea Collection. D.2.10-11) utilizes both foot and margin notes to display information to the reader.[7]

In the 1885 periodical, the text is formatted into two columns per page with two columns in the middle for margin notes. Short, explanatory notes appear in the inner margins, marked by superscript numerals, that reset back to 1 at the top of each column.

At the bottom of certain columns are critical footnotes that are flagged by symbols that follow the traditional pattern of *†‡ etc. The editor of the periodical is able to best organize the information he is trying to convey to the reader by printing explanatory notes as margin notes and critical notes in the footnotes. The explanatory notes, which appear more frequently and are needed more by the reader, appear in the margins so that they are more easily referenced. The critical notes are relegated to the footnotes because they appear infrequently and are needed less for the reader’s understanding of the text. It is likely that the editor chose to use footnotes and margin notes instead of footnotes and endnotes because they wanted to use less paper to keep the costs on this relatively cheap periodical down and extra paper needed to print endnotes would not have helped.

The Furness Shakespeare collection

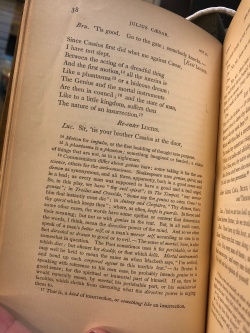

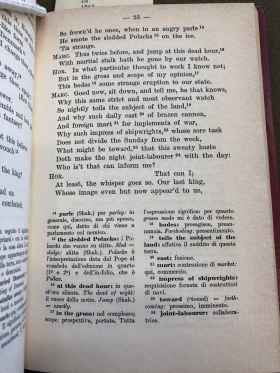

The Kislak Center at the University of Pennsylvania Libraries has many rare editions of Shakespeare, including many from the Furness Shakespeare collection that have extensive footnotes. The collection includes an Italian copy of Hamlet, printed by the International Publishing Company of Turin in 1965 (PR2807.A2 C4 1965), that features Italian footnotes to an English text.[8]

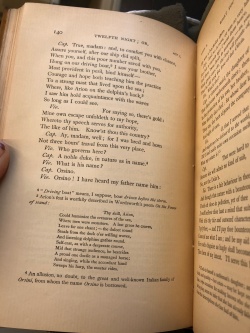

An introductory page that features phonetic symbols to help Italian readers properly pronounce Shakespearean English includes two footnotes, marked by “*” and “**” give notes on vowels and consonants for the reader. Interestingly, these are the only notes in the book marked by symbols, and they do not use the traditional symbol pattern of *†‡§, etc. In the text of the play, footnotes are used to clarify words or phrases that may be confusing to the Italian reader. Notably, these notes are in Italian while the actual text of the play is in English. These textual footnotes are marked by superscript numerals and are organized into two columns at the bottom of the page. At the end of each scene the numbering of the footnotes is reset, so in some scenes the footnotes reach upwards of one hundred. While the footnotes in this edition of Hamlet are in Italian, these notes are mostly explanatory. On page 23, a note clarifies for Italian readers that “mart: contrazione di market: qui, commercio;” this note both translates and clarifies English jargon for Italian readers. A note on page 39 explains the English phrase “I doubt some foul play” that may be confusing for non-native speakers. An 1881 edition of The Complete Works of William Shakespeare; Harvard Edition, revised by Henry Hudson, (90 1880H) uses a slightly different tactic for the organization of its notes. In this edition the footnotes are also marked with superscript numbers but appear in one column at the bottom of the page.[9] The numbering of the footnotes also restarts at the beginning of each page. While these footnotes are described as “explanatory foot-notes” on the title page, they take on a much more extensive and editorial than in the Italian edition of Hamlet discussed above.

A note from page 181 of Hamlet, includes a note with a quote from Dr. Issac Ray which describes him as “a man of large science and ripe experience in the treatment of insanity, says of Hamlet’s behavior” that “‘it betrays the excitement of delirium,– the wandering of a mind reeling under the first stroke of disease.’” While this note is helpful for the reader to better understand text, it is a note that is more than simple analysis and is used to comment on the text in a way that is more reminiscent of the way footnotes were used prior to Leopold von Ranke’s views on modern documented historiography. A note of this style would never have appeared in the 1965 Italian edition of Hamlet.

Because these notes are lengthier, the footnotes section of the page often takes up half of the page in the dramas such as Julius Caesar and Hamlet. The comedies, As You Like It and Twelfth Night, feature fewer and shorter footnotes, but they too contain notes that are more editorial than the Italian edition was. One note on page 140 of Twelfth Night, contains an eleven-line excerpt of a Wordsworth poem in order to explain the reference to Arion, a creature from Greek mythology, that appears in the text of the play. This edition of Shakespeare’s works also contains extensive critical endnotes at the end of each play. These endnotes contain information about differences between this edition and previous editions of the play. These notes can be very helpful to the reader because of the fluid nature of Shakespeare; many sections of what we consider to be officially the words of Shakespeare did not appear in the First Folio as noted in a critical note on Act I, Scene I of Hamlet. This endnote specifies about one line containing the word “climature” that “The quartos have climatures. Not in the folio.” By organizing the explanatory and critical notes in this way, the reviser, Henry Hudson, makes this edition accessible for first time readers and Shakespeare scholars alike. Additionally, it is useful that the endnotes are organized for each play at the end of its text. There are two plays per volume and 20 volumes in the complete set, so positioning the endnotes at the end of each play made them more accessible for the reader.

The Significance of the History of Early Chemistry

A 1965 paper by Allen G. Debus, The Significance of the History of Early Chemistry (QD14 .D423), exhibits footnotes that that reflect the style of modern documented historiography that Leopold von Ranke started.[10] The footnotes in this paper contain extensive information on the works referenced an where they were found. Note 17 on page 45 contains background information on the “current state of the study of Islamic alchemy” which the author mentions only briefly in the paper itself. While these footnotes are presented in a more formal academic style than the Harvard edition of Shakespeare’s works discussed above, they still contain more than citations alone. Note 53 on page 52 contains expanded information on medieval alchemists that is not included in the text above. This paper exemplifies the downsides of footnotes; on many pages, the footnotes take up over half the page. The benefit of this kind of extensive footnote is that it allows the reader to see immediately and in full the sources from which the information comes, any other background information needed, and how to find these sources for themselves.

It is important too to consider the target audience of a piece of work when formatting the footnotes. The audience of Debus’s paper would have likely been scientific historians who would’ve already had a baseline knowledge of the subject and may have been interested in reading the references themselves. In contrast, the audience of the two editions of Shakespeare discussed above would have been a greater range of armature Shakespeare readers to Shakespeare scholars. The notes are organized so that basic information necessary for the comprehension of the plays appeared as footnotes on the pages they were needed while critical notes, which would have been more useful for scholars, appeared at the end of each play.

Notes

- ↑ USC Libraries Research Guide, Footnotes or Endnotes? https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/notes

- ↑ Sherman, William H. Toward a History of the Manicule. 2005 http://www.livesandletters.ac.uk/papers/FOR_2005_04_001.pdf

- ↑ Grafton, Anthony. The Footnote: A Curious History. [Rev. ed.]. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1997.

- ↑ Major, David. Anthony Grafton Defends the Footnote, Princeton Alumni Weekly. https://paw.princeton.edu/article/anthony-grafton-defends-footnote

- ↑ Cermak, Bonni, Jennifer Troxell. Guide to Footnotes and Endnotes for NASA History Writers. https://history.nasa.gov/footnoteguide.html

- ↑ U.S. Government Printing Office Style Manual: Chapter 15 - Footnotes, Indexes, Contents, and Outlines. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/GPO-STYLEMANUAL-2008/html/GPO-STYLEMANUAL-2008-17.htm

- ↑ The Revised version of the Old Testament: with marginal notes and the readings preferred by the American revisers printed as footnotes in four parts – Part 1: Genesis- Deuteronomy. Harper & Brothers 1885, from Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Pennsylvania.

- ↑ Shakespeare, William. Hamlet. Società editrice internazionale, Turino, 1965, from Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Pennsylvania.

- ↑ Shakespeare, William. The complete works of William Shakespeare: with a life of the poet, explanatory foot-notes, critical notes, and a glossarial index, volumes V and XIV. Ginn & Heath, 1881, from Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Pennsylvania.

- ↑ Debus, Allen G. The Significance of the History of Early Chemistry. The Journal of World History, 1965, from Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Pennsylvania.