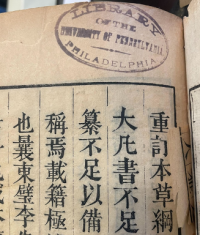

芥子園重訂本草綱目:a reprint version in Qing Dynasty of the Bible of Traditioanl Chinese Medicine

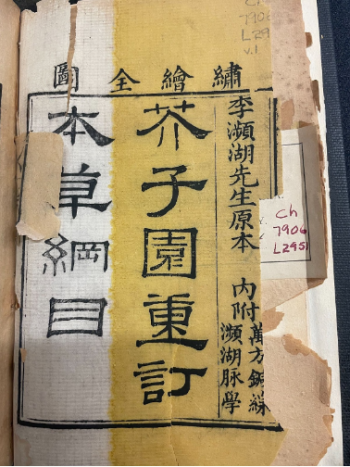

Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu (本草綱目) is one of the most famous encyclopedia for Chinese Traditional Medicine, known as the “Compendium of Materia Medica”. It has huge historical significance in Chinese Medicine, and is regarded as “the highest academic achievement among all ancient Chinese Medicine literature” [1] up to the 16th century. The original version of Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu was written, summarized and edited by the famous herbalist, physician and pharmacologist, Li Shizhen (李时珍), in the late 16th century during Ming Dynasty of China. The book has 52 volumes in total, and was first published in 1596 during Ming dynasty in Nanjing, China[2]. The version of the book demonstrated here is a Re-print version published in 1657 during Qing Dynasty, nearly 60 years after the first publication of the original Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu. It was published by Li-Yu (李渔), a famous playwright and novelist in the Qing dynasty, who used the name of his mansion and also his own publishing company, “Jie-Zi-Yuan” (芥子園), as the publisher name for this re-print.

This particular version of Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu is named as Jie-Zi-Yuan-Chong-Ding-Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu (芥子園重訂本草綱目), and is especially interesting to explore not only because it allows us to understand more about the development of traditional Chinese Medicine, more importantly, the re-print version itself provides invaluable information about the history of publishing, copyright and authorship in China during Ming and Qing Dynasty. This book was collected by Penn Library around early 1900s, and its circulation history at Penn is also very interesting.

Historical Significance

Historical Significance of Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu in Chinese Traditional Medicine

Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu (本草綱目) is one of the most comprehensive Medical Books ever written in the history of Traditional Chinese Medicine. The original author, Li-Shi-Zhen (李时珍) completed the first draft in 1578 during the Ming Dynasty when China was governed by emperor Wanli (万历)[3], and it took Li-Shi-Zhen nearly 27 years to finish compiling and editing the book to its final published version.[3]. Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu has unique historical significance in Chinese Traditional Medicine because of its comprehensive medical literature list, and also the innovative classification system developed by Li-shi-zhen to better classify, and understand the medical properties of objects with an evidence-based approach.

Comprehensive Medical Knowledge coverage through extensive reading

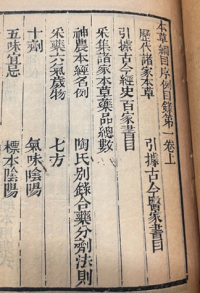

Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu is an encyclopedic work heavily based on the results and conclusions from previous medical literature in Chinese Traditional Medicine up until the 16th century. In order to have sufficient knowledge to complete such a huge project, the author Li-shi-zhen searched for probably “more than 800 different sources” [4], extensively read and reviewed numerous medical literature, especially the ones on herbal medicine.

Before citing the literature in his book, Li-Shi-Zhen evaluated the conclusions in previous literature through comparison with his own observation and practices in medicine. Among all the medical literature that was cited in Beng-Cao-Gang-Mu, Herbal medicine literature had the most abundant sources. There were 42 kinds of herabl medicine sources cited in Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu, and 9 of them were books written in the same dynasty (Ming Dynasty), including 3 of Li-Shi-Zhen’s own work, as well as 6 other books: Ben-Cao-Fa-Hui本草发挥,Ben-Cao-Ji-Yao本草集要,Shi-Wu-Ben-Cao食物本草,Shi-Jian-Ben-Cao食鉴本草,Ben-Cao-Meng-Quan本草蒙筌,Ben-Cao-Hui-Bian本草汇编.[5]

If Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu is published today, it would be the “medical review” article where clinical physician and scientists get their background knowledge. The idea behind a “review” and Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu is the same: it is a comprehensive compilation and careful selection of knowledge from previous work based on extensive reading. Li-Shi-Zhen was able to equip himself with sufficient knowledge to ensure the credibility of the content cited and written in Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu. As a physician and a herbalist himself, he also had the opportunity to have the latest information in the medical field through his own medical education as well as his practicing experiences, which all enabled him to examine the credibility of previous knowledge and fill in the gap between previous and present work through critical thinking.

Innovative classification system for medicine

Another key feature of Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu that contributes to its historical significance is the innovative classification system of the medical objects. Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu has included 11,096 medical treatment recipes with 1,094 plant-based drugs, 276 mineral-based drugs, and 444 anima material-based drugs for different diseases[5]. It also features 1892 different medical objects, dividing them into 16 outlined classes and further into 60 sub-class categories[5]. Compared to Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu, previous Chinese Medical work only covered a small number of medical objects: for example, in Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing, another famous Chinese medicine encyclopedia that was written back in the Han Dynasty (which was 6 dynasties before the Ming Dynasty), it only included 365 medical objects [1]. The reason for Li-Shi-Zhen to be able to cover such a large number of medical objects in Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu is that additional medical objects were added into this book. These medical objects were found in regions that were not part of the Chinese Empire before Ming Dynasty [6], and were probably imported from foreign countries, such as jasmine, camphor, and tulips. They were most likely to enter China through trading via the silk-road, which was a commercial trading network connecting the east to the west established in Han Dynasty, and continued through the Ming Dynasty. Through commercial trading and exchange with foreign countries for about 6 dynasties, there must be more novel medical objects imported and exchanged through the trading, so that’s probably why in Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu, more medical objects were documented than previous work.

Besides a more comprehensive range of medical objects covered, the system to classify these medical objects is also ground-breaking in the history of Traditional Chinese Medicine, which drives the development of Modern Chinese Medicine. Before Beng-Cao-Gang-Mu, the way to classify medical materials and objects mainly followed the classification system described in Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing: the Three-Grade Classification[5]. All the medical objects were classified as either high, medium or low grade according to their toxicity, properties, medical applications and efficacies [1]. However, in Beng-Cao-Gang-Mu, Li-Shi-Zhen developed a much more sophisticated and empirical classification system by dividing the major classes of medical objects further into different sub-categories according to their natural habitat, morphology, chemical properties, medical properties, and treatment efficacies. For example, within the class of herbs, Li-Shi-Zhen further classified the herbs into: mountain herbs, fragrant herbs, marshland herbs, poisonous herbs, aquatic herbs, stone herbs and moss[4]. This sub-classification of herbs was based on their size, structures, natural habitats, fragrance properties, and medical effects. Compared to the general classification system used in Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing, which only had three categories and did not differentiate medical objects based on their individual properties, Li-Shi-Zhen’s classification in Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu was based on more comprehensive research on the properties and background of these herbs, which enabled him to develop a more accurate classification system.

This classification approach is also significant in the development of modern scientific thinking in China. The classification is not simply based on observation of the difference in object morphology, in addition to that, it incorporates evidence from previous documented use of medical object, reported efficacies and physician Li-Shi-Zhen’s own judgement from his medical practice, addressing the subtle differences among different medical objects. This empirical approach [3] demonstrates an early form of evidence-based and critical thinking skills that play an important role in scientific research today.

Promotion of Chinese Medicine in the Ming Dynasty

The Ming Dynasty was the second last imperial dynasty of China lasting from 1368 to 1644, ruled by 16 emperors from the Hongwu Emperor (real name Zhu Yuanzhang) who established the Ming Dynasty, to the Chongzhen Emperor, the last emperor of Ming Dynasty.

During the Ming Dynasty, the highly centralized government structure provided great social stability, which led to the flourishment of both artistic and intellectual inspirations [7]. The emperor, as well as the governors of states and provinces (who were the relatives of the emperor), were starting an initiative to promote medicine and healthcare by actively pushing the compilation and publication of medical literature, either by themselves, or through collaborations with certified physicians[5].Examples of medical works published under this initiative include Jiu-Huang-Ben-Cao (救荒本草) by state governors Zhu su and Zhu Quan.

History of Original Authorship, copyright and Reprint

History of Authorship

Li-Shi-Zhen (1518-1593) finished his medical education in his twenties, and start working as a medical official and physician in the medical institution later on. The medical institution was located in the palace of a state governor named Zhu Ying Xian (also known as King or Prince Chu). Li-Shi-Zhen was working in the department called “Good Doctor Department (良医所)”[5], and was motivated by the massive compilation and publication processes going on for other medical works. He presented his idea of writing, summarizing, and compiling the medical compendium to governor King Chu, but was turned down by the governor. He finally left his job in the medical institution and started working on Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu on his own – it took him nearly 27 years to finish editing and writing the whole book[3]. The first draft of this book was finished in 1578, but it was not published and printed after Li-Shi-Zhen’s Death, by a publisher named Hu Chenglong in Jingling, Nanjing (the formal capital of China before the third Ming emperor). There are some discrepancies in the exact year recorded when the first version of Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu was printed: some scholars suggested that it was printed in 1593, during Li-Shi-Zhen’s last year, and the contents were proofread and verified by Li’s family [8]. Other scholars have suggested that the first version was printed in 1596[9].

Copyright and Reprint in the Qing Dynasty

The Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) is the last imperial dynasty in China, and it follows the Ming Dynasty. The Qing Dynasty was established by Manchu with a highly centralized government structure and had huge social turbulence in its later years.

The original version of Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu underwent a re-organization and revision in 1640, right before the establishment of Qing Dynasty. It was re-recognized by people in the Qing Dynasty after this revision and was very frequently re-printed during Qing Dynasty, having “at least 15 editions”[9]. The recorded editions of Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu during Qing Dynasty were around 1658, 1684 and 1717[9].

Interestingly, the re-print version here was published in 1657, which was just around the first edition period documented during the Qing Dynasty for Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu. This Re-print version was published by a publisher named “Jie-Zi-Yuan(芥子園)”.

The history and origin behind the Re-print publisher Jie-Zi-Yuan (芥子園)

Jie-Zi-Yuan (芥子園) is not the name of a person, instead, it is actually the name of the mansion where a famous novelist and playwright named “Li-Yu (李渔)” from the Qing Dynasty resided. Li-Yu wrote a lot of short novels, essays, and comedic works, but was also a dedicated publisher. Jie-Zi-Yuan was located in Nanjing, which was the former capital of China before the third emperor of Ming Dynasty. After that, the later emperors moved the capital to Beijing, which is the capital of China today. Nanjing was the cultural center in China during Ming and Qing Dynasty where a lot of famous writers, poets, and artists lived. The publishing industry flourished in Nanjing starting from Ming Dynasty when the first emperor of Ming (Zhu-Yuan-Zhang, known as Hong-Wu Emperor) recruited craftsmen who specialized in woodcut printing to be trained in the publishing companies in Nanjing, leading to the development of the publishing industry. [10]

Before moving to Nanjing, Li Yu’s novels, plays and literature works were pirated by publishers from other parts of China, and he was really frustrated. Attracted by Nanjing’s prosperous publishing industry with its standardized publishing process and protection for copyright, he moved to Nanjing around 1657[10], established his own publishing company using the name of his mansion, and run the company with help from his son-in-law. Worth noting, this re-print version of Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu was published in 1657- the time matched exactly with the approximate time when Li Yu moved to Nanjing. Li-Yu not only published his own work but also a lot of other famous or popular books in his own publishing company in order to attract customers. Since Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu was re-recognized in Qing Dynasty and was still very famous, that’s probably why Li-Yu decided to re-print and publish this work in his own publishing company.

Book Feature

Substrate

The substrate of this book is paper. The first page of this book with publisher information was made with a different kind of paper than the rest of the pages. The paper used for this page has a cream-white color. The chain lines on the paper indicate that the paper was probably hand-made. This kind of paper is actually very similar to a type of paper called “Xuan paper” (宣纸), or “rice paper” in China, which is primarily used for printing and artistic purposes such as chinese water painting and calligraphy. During Qing Dynasty, the paper-production industry expanded very rapidly[11]. The Xuan paper used here was probably made of the bark of elms, which was one of the major materials for xuan paper [12], or rice or bamboo which were used in earlier times.

Also, if we compare the font of the text in this title page with that in the rest of the book, the difference in the regularity of the font suggests that the Chinese Characters on this title page were probably hand-written using ink and soft brushes. The use of “Xuan paper” for this title page also agreed with this hypothesis because Xuan paper was mainly used for practicing Chinese Calligraphy and was suitable for hand-writing using Chinese soft Brushes. The rest of the pages in this book were made from another type of paper with a yellow and brown color.

The paper from this book is extremely fragile and crispy - when I was examining the book, I had to be very gentle when carrying the pages, otherwise, the pieces from the pages would immediately fall apart. The fragility of the paper is probably due to 2 reasons: First, The book was published in 1657, which was 366 years ago, so the material probably degraded and that’s why the paper is so fragile. Second, probably it’s also because the paper is hand-made, so it lacks industrial processes or additions to strengthen it.

Format

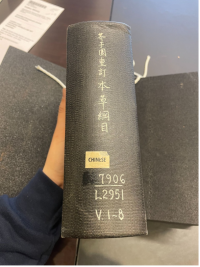

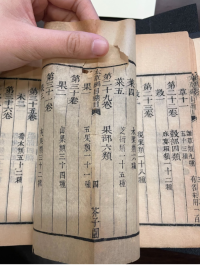

The original Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu has 52 volumes in total, but only 47 volumes are collected by the Kislak Center at Pennand bound into 6 “books” in codex format, each containing 8 volumes. The re-print demonstrated here is book one with the first 8 volumes of Jie-Zi-Yuan Reprint Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu.

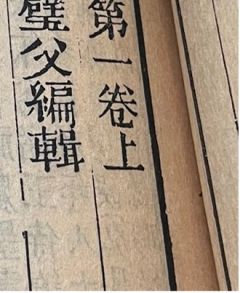

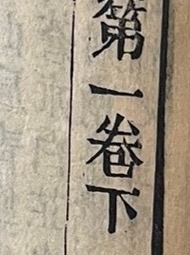

The original format of Jie-Zi-Yuan Reprint Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu is probably separated as individual volumes. The numbers from “1” to “8” on each volume of the book suggest that the volumes were separated before the library binding.

Binding

The library re-binding combined every 8 volumes of the original book together into a new book in codex format. The book now has a hardcover, with information including the title of the book, library identification number, language category as well as volume number recorded on the spine.

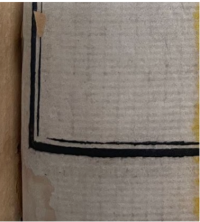

Though the library combined the volumes and bound them together in a codex format, the original binding of Jie-Zi-Yuan Reprint Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu did not follow any traditional bibliographic formats. It is an example of a traditional Chinese binding that combines “thread binding” and “Wrapped back binding” which originated from “butterfly binding”. “Butterfly binding” was developed in the Tang dynasty (618 to 907) and became popular in the Song dynasty (960 to 1279). In butterfly binding, each printed sheet of paper was folded in half. The printed pages faced directly to each other, and these sheets were pasted together to form a book[13].At the first glance, the volumes of this Jie-Zi-Yuan Reprint Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu seem to be bound by butterfly binding, but the folded edge of the sheet of the paper is facing outward in this book – this suggests that it is bound most likely by wrapped-back binding. Wrapped-back binding was widely used in the Ming Dynasty, and it originated from butterfly binding. The only difference between butterfly and wrapped-back binding is that the folding of the sheet of paper is reversed in Wrapped-back, so the printed pages are on the outside, with the edges of the paper facing inside and being bound together. Most importantly, with wrapped-back binding, the fold on the sheet is now at the fore-edge of the book[13]– this corresponds to what we’ve seen on the fore-edge of this book. Normally books with “butterfly” or “wrapped-back” binding paste the pages together, but this book applies “thread binding” instead of pasting- the pages are sewn together with threads. Thread binding is used to prevent insect harm to the paste[13]. From the picture we can clearly see traces of white threads used to sew the sheets together.

Book Use

The wrapped-back binding of this book helps navigate the readers when they are reading the book. The area folded on each sheet of paper contains information about the chapter title, chapter number, and volume number (in order, from top to down). Unlike books with butterfly binding where the fold is inside, in this book, wrapped-back binding enables the fold on the sheet to face outwards and be at the fore-edge of the book. This really helps the reader to better navigate the content of a long catalog book, knowing which chapter and volume they are at while reading. Also, it helps the readers to find desired information much more quickly, as they can easily navigate to the content they are looking for using the information on the fore-edge fold.

Vertical Margins

Another element from this book object that might help the readers to navigate the content is the vertical line (or the vertical margin) on each page. These vertical margins are very similar to the margins that appeared on the letter practicing books, and they help organize the texts into a clearer structure. These vertical margins separate the texts into distinct columns, and help prevent the texts from overlapping with each other - this feature helps the readers to navigate the contents better as they will have a better sense of the flow of the content. Also, the vertical margins suggest that the texts are meant to be read from top to down, which navigates the reader to read in this order.

The right-most vertical margin on the page is much thicker than the other lines in between the texts, which suggests that the contents start from here, on the right side of the page, and navigates the readers to read in a right-to-left and top-to-down order.

This mechanism informs us about the different expectations readers have in terms of the order in which they should read the text - different readers under different cultures may have different expectations towards the way in which the texts are ordered. In most Western books, the texts are written and meant to be read horizontally, from left to right, but in books from East Asia, the texts are often written and read from right to left and organized in vertical columns. This mechanism tells us that probably the readers are assumed and expected to be comfortable with reading from top to down, right to left - but if the readers are coming from a culture in which the texts are organized in horizontal order, these vertical columns and margins will help them re-orient the way they read the texts and navigate them through the whole book.

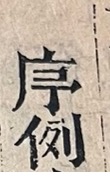

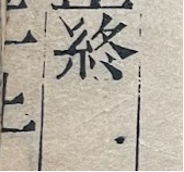

Repetitive Notation marking start and end of each chapter and volume

Other elements this book has which help readers navigate are the repetitive notations marking the beginning, end, and the location of the content within the whole volume. These notations are consistent in the meaning they represent throughout the whole book, and are used repetitively in every volume. Common examples of these notations are : 上 (first half of content), 下 (last half of content), 序 (beginning), and 终 (end). They help the readers to navigate different contents from the different chapters and volumes of this book. This mechanism tells us that probably the readers are expecting different volumes of the book to discuss different contents and aspects of Chinese herbal medicine, so all these notations will navigate them and inform them about where they are in the book.

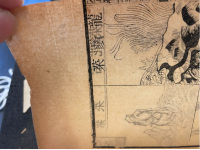

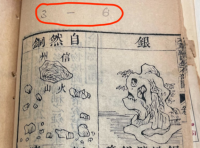

Annotations

There are number annotations in the margin area for the graphic sections of this book - surprisingly, the numbers annotated align well with the actual total number of graphs on each page, and recur on every single page of the volumes with pictures in this book. This suggests that probably one of the readers ordered all the graphs by assigning individual numbers to every one of them. These number annotations tell us that the graphic section of this book was probably read in the order by which the graphs appeared on each page. The readers do not jump between different pages and different graphs - instead, they view the graphs in an anti-clockwise order on each page, and followed page by page. It is unknown by whom these annotations were written, as there were no names recrode. But these number annotations were written in pencil, so probably they were annotated by a more modern reader, probably not until the 1900s when pencils became a popular writing tool.

Book Circulation History

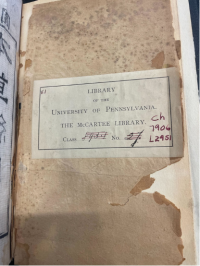

The former owner of Jie-Zi-Yuan Reprint Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu (芥子園重訂本草綱目) was McCartee Divie Bethune (1802-1900). He was born in Philadelphia, and was a Protestant Christian medical missionary[14], and also the U.S. diplomat to China. He traveled to China in 1843, opened mission and organized Protestant Church, and also worked as an interpreter as well as a temporary American Consul in China before his return to the U.S. around 1880s [15]. The time when McCartee traveled to China was during late Qing Dynasty, right after the first opium war (from 1839 to 1842). During these years, there were huge transformations in regime and social structure and the social environment was highly turbulent in China. Since McCartee was a medical missionary, he probably collected this book during his medical work and research when he was in China as Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu was one of the most important books in Traditional Chinese Medicine History.

McCartee donated Jie-Zi-Yuan Reprint Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu (芥子園重訂本草綱目) to Penn, and after that, the book was circulated among different Penn Libraries until today, as evidenced by different bookplates and library stamps on the page. The exact time when McCartee donated the book to Penn was unknown, but it was most probably around late 19th century and early 20th century. The bookplate from McCARTEE library was probably the oldest bookplates among all the ones. This bookplate appears on the first page of every single volume of this book, which suggests that Penn Library first collected this book in separate volumes. The library was name after McCartee because he donated a lot of books to Penn, and was probably around late 19th century. The other bookplate and the book-stamp were probably from mid 1900s. The bookplate with “University of Pennsylvania, rare book and manuscript library” is the most up-to-date one and is probably from the 21st century when the kislak center for special collections, rare books and Manuscripts was built.

Evidence of Readership

Interestingly, this book was first placed in regular shelves when Penn Library first collected it. The borrowing card, showing that somebody borrowed it in 1970 and 1974, shows evidence of readership back in 1900s. This borrowing card suggests that book is still on the regular shelf where people can take and read it freely in the 1970s – probably the book had more readers back in the 1900s when it was still on the regular shelf than today. The bookplate from Kislak suggested that this book was probably not identified as rare book and protected until the 21st century. After it was collected by Kislak center, the book is identified as a rare book and finally being properly protected.

Referrences

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Zhao, Z., Guo, P., & Brand, E. (2018). A concise classification of bencao (materia medica). Chinese medicine, 13, 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13020-018-0176-y

- ↑ Theobald, U. (n.d.). Bencao gangmu 本草綱目. Retrieved May 3, 2023, from Ulrich Theobald website: http://www.chinaknowledge.de/Literature/Science/bencaogangmu.html

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Cao, B., Mu, G., & Zhang, H.-M. (n.d.). Memory of the world register. Retrieved May 3, 2023, from Hustoj.com website: http://orcp.hustoj.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Ben-Cao-Gang-Mu%E3%80%8A%E6%9C%AC%E8%8D%89%E7%BA%B2%E7%9B%AE%E3%80%8B.pdf

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Theobald, U. (n.d.). Bencao gangmu 本草綱目. Retrieved May 3, 2023, from Ulrich Theobald website: http://www.chinaknowledge.de/Literature/Science/bencaogangmu.html

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Yang, D., & Yang, X. (2019). Historical background of Ben Cao gang mu (《本草纲目》 Compendium of Materia Medica). Chinese Medicine and Culture, 2(1), 32. doi:10.4103/CMAC.CMAC_8_19

- ↑ p14, Wood, F. (2003). The silk road: Two thousand years in the heart of Asia. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=Z5eyku1AmkoC&oi=fnd&pg=PA7&dq=silk+road&ots=kEIDaOfOYW&sig=z21rug6yqzrODQBQbS9oX4xOqGU#v=onepage&q=silk%20road&f=false

- ↑ p21, Ho, S.-Y. (n.d.). The Ming Dynasty : a renaissance in medical thought. Retrieved May 3, 2023, from Yale.edu website: https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2719&context=ymtdl

- ↑ Ben cao gang mu: Wu shi er juan, fu tu er juan. (1603). Jiangxi Sheng: Zhang Dingsi.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Dorr, S. D. /. (n.d.). Li shizhen: Scholar worthy of emulation. Retrieved May 3, 2023, from Itmonline.org website: http://www.itmonline.org/arts/lishizhen.htm

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 新华日报. (2018, March 30). 古都南京有部千年阅读史. Retrieved May 3, 2023, from Com.cn website: http://news.sina.com.cn/o/2018-03-30/doc-ifystnux4294357.shtml

- ↑ 王楠. (n.d.). Xuan Paper Making Techniques. Retrieved May 3, 2023, from Chinaculture.org website: http://en.chinaculture.org/2014

- ↑ 宣纸. (n.d.). Retrieved May 3, 2023, from https://web.archive.org/web/20110707094406/http://www.ahlib.com/ahlib/tszy/gongyimeishu/wenfangsibao/xuanzhi.htm?subfcode=007090110

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Introduction to Chinese traditional book making - Victoria and Albert museum. (2011, January 11). Retrieved May 3, 2023, from Vam.ac.uk website: http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/journals/conservation-journal/issue-38/introduction-to-chinese-traditional-book-making/

- ↑ (N.d.-b). Retrieved May 3, 2023, from Cornell.edu website: https://ecommons.cornell.edu/bitstream/handle/1813/29911/Z199_20_0929.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- ↑ Divie Bethune McCartee. (2022, May 10). Retrieved May 3, 2023, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Divie_Bethune_McCartee#cite_note-Twentieth-1