La femme heroique, ou les heroines comparées avec les heros en toute sorte de vertus...: Difference between revisions

| (88 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

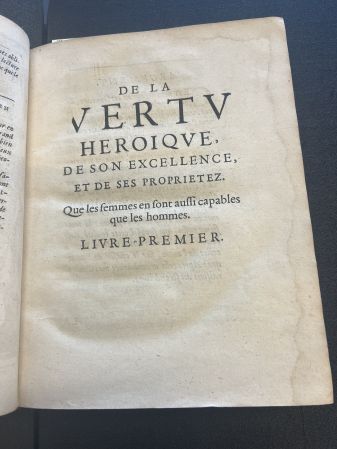

[[File:FirstPageVolumeI.jpeg|300px|thumb|right|Title Page of ''La Femme Heroique'' Volume I]] | |||

==Overview== | ==Overview== | ||

| Line 6: | Line 8: | ||

===Historical Context=== | ===Historical Context=== | ||

Importantly, ''La femme heroique'' was published in the middle of a crisis and transformation within the book industry in France. After the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_Wars_of_Religion French Wars of Religion (1562-1598)], the economy of France destabilized, heavily impacting the book industry. During this time, there was a lack of books being printed. The Postman of the Plantinian Press Théodore Reinsart testified to this when he said that because of the low supply of books he "could not chase the people out of the room where they were books and sometimes there were as many as 50 people there together.” <ref name="malcolm">Walsby, Malcolm. | Importantly, ''La femme heroique'' was published in the middle of a crisis and transformation within the book industry in France. After the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_Wars_of_Religion French Wars of Religion (1562-1598)], the economy of France destabilized, heavily impacting the book industry. During this time, there was a lack of books being printed. The Postman of the Plantinian Press Théodore Reinsart testified to this when he said that because of the low supply of books he "could not chase the people out of the room where they were books and sometimes there were as many as 50 people there together.” <ref name="malcolm">Walsby, Malcolm. "Les étapes du développement du marché du livre imprimé en France du XVe au début du XVIIe siècle." Revue dhistoire moderne contemporaine 673, no. 3 (2020): 5-29.</ref> | ||

Additionally, the few books that were being printed were made with cheaper materials. The book-making industry turned to smaller amounts of gelatin and calcium in the paper making process, thinner paper when publishing books, copper engravings for illustrations instead of [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wood_engraving wood engravings], and even developed a new book format known as the [https://www.biblio.com/book_collecting_terminology/Duodecimo-234.html duodecimo], which saved costs due to its smaller size.<ref name="malcolm"/> On top of the cheaper quality, these books were not being circulated outside of their respective regions due to the economic hardship in France. For example, numerous seventeenth century testimonies corroborate that books published in Paris could not be imported for circulation in other parts of France. <ref name="malcolm"/> | Additionally, the few books that were being printed were made with cheaper materials. The book-making industry turned to smaller amounts of gelatin and calcium in the paper making process, thinner paper when publishing books, copper engravings for illustrations instead of [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wood_engraving wood engravings], and even developed a new book format known as the [https://www.biblio.com/book_collecting_terminology/Duodecimo-234.html duodecimo], which saved costs due to its smaller size.<ref name="malcolm"/> On top of the cheaper quality, these books were not being circulated outside of their respective regions due to the economic hardship in France. For example, numerous seventeenth century testimonies corroborate that books published in Paris could not be imported for circulation in other parts of France. <ref name="malcolm"/> | ||

| Line 18: | Line 20: | ||

The book aligns with other feminist literary works published during the seventeenth century. While French feminism and literature is often linked to the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_Revolution French Revolution]in 1789, writers, both male and female, were publishing important works advocating for equality of the sexes prior to the eighteenth century. In alignment with the book’s focus on moral virtue, other feminist writers during the seventeenth century also advocated for equality with a heavy religious underpinning prior to Du Bosc. | The book aligns with other feminist literary works published during the seventeenth century. While French feminism and literature is often linked to the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_Revolution French Revolution]in 1789, writers, both male and female, were publishing important works advocating for equality of the sexes prior to the eighteenth century. In alignment with the book’s focus on moral virtue, other feminist writers during the seventeenth century also advocated for equality with a heavy religious underpinning prior to Du Bosc. | ||

The most renowned of these writers was the French feminist writer [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marie_de_Gournay Marie de Gouray (1565-1645)]. In her “Equality for Men and Women (1622)” de Gournay argues that men and women are of equal virtue “only by the authority of God himself and of the Fathers who were buttresses of his Church, and of those great philosophers who have enlightened the universe” (55).<ref name="desmond">Desmond, M. | The most renowned of these writers was the French feminist writer [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marie_de_Gournay Marie de Gouray (1565-1645)]. In her “Equality for Men and Women (1622)” de Gournay argues that men and women are of equal virtue “only by the authority of God himself and of the Fathers who were buttresses of his Church, and of those great philosophers who have enlightened the universe” (55).<ref name="desmond">Desmond, M. Equality of the Sexes-Three Feminist Texts of the Seventeenth Century. Oxford University Press, 2013.</ref> Additionally, in her “The Ladies’ Complaint (1626)” De Gournay builds on her religious feminist perspective by outlining the inequality that women in French society experience, which she claims strips women of virtues that men are able to obtain with the privileges they are granted. <ref name="desmond"/> Du Bosc’s ''La femme heroique'' fits well into the religious feminist literary works that were being published during the seventeenth century, setting the stage for the plethora of works that would later be published during the French Revolution in the eighteenth century. | ||

==Material Analysis== | ==Material Analysis== | ||

===Binding=== | ===Binding=== | ||

''La Femme Heroique'' is bound with a leather calfskin cover with | ''La Femme Heroique'' is bound with a leather calfskin cover with black spots and gold tooling. This was a typical binding method used in France during the seventeenth century, as exemplified by other important works published in Paris during this time period like ''Traité de la comedie et des spectacles : selon la tradition de l'église, tirée des conciles & des saints pères''. <ref> “17th century: Refinement in style.” Michigan State University Libraries. https://lib.msu.edu/exhibits/historyofbinding/17thcentury </ref> In ''La Femme Heroique'', gold tooling is used to draw decorative lines on the covers of each volume as well as to separate the spine of the book into six sections. The second section on the spine in each volume includes the name of the book, “LA FEMME HEROIQUE”, in gold and the third section includes the volume of the book, either “TO.I” or “TO.II.” The remaining sections on the spine use gold tooling to create a flower-like design. Such a creative bookbinding aligns with seventeenth century efforts in France to make the binding process rich and beautiful. <ref name="diehl">Diehl, Edith. ''Bookbinding: its background and technique''. Courier Corporation, 2013.</ref> | ||

As was customary during the seventeenth century, the gold tooling for this book was specifically done by a skillful person with several years of experience. This is because gold tooling was a complex process that could easily damage the book or fail if the individual did not have an understanding of the right amount of heat to add to each type of leathered cover. For example, if the heat applied was too hot for a particular leather, the impression would burn the cover of the book. If the heat applied was too cold, the gold would not stick onto the cover, and the gold tooling process would fail. <ref name="diehl"/> Given that the gold tooling on ''La femme heroique'', whether it be the title on the spine of the book or on the decorative lines on the front and back covers, remains intact with no signs of burns, we know that the book was bound by an experienced and skillful person in the book industry during the seventeenth century. | As was customary during the seventeenth century, the gold tooling for this book was specifically done by a skillful person with several years of experience. This is because gold tooling was a complex process that could easily damage the book or fail if the individual did not have an understanding of the right amount of heat to add to each type of leathered cover. For example, if the heat applied was too hot for a particular leather, the impression would burn the cover of the book. If the heat applied was too cold, the gold would not stick onto the cover, and the gold tooling process would fail. <ref name="diehl"/> Given that the gold tooling on ''La femme heroique'', whether it be the title on the spine of the book or on the decorative lines on the front and back covers, remains intact with no signs of burns, we know that the book was bound by an experienced and skillful person in the book industry during the seventeenth century. | ||

<gallery mode="packed" heights=300px> | |||

Image:Cover La Femme HeroiqueHEIC.jpg| Leather Calfskin Cover of ''La Femme Heroique'' | |||

Image:BindingSide.jpeg|Gold Tooling on Side of ''La Femme Heroique'' | |||

</gallery> | |||

===Navigational Features=== | ===Navigational Features=== | ||

''La Femme Heroique'' has several navigational features. First, it has a Table of Contents, labeled “Table de Matieres” to help the readers navigate the lengthy 300+ page two volume book. The Table of Contents is placed at the end of the book, as is common practice in French books. <ref | ''La Femme Heroique'' has several navigational features. First, it has a Table of Contents, labeled “Table de Matieres” to help the readers navigate the lengthy 300+ page two volume book. The Table of Contents is placed at the end of the book, as is common practice in French books. <ref>Nelson, Brent. "Table of Contents." Implementing New Knowledge Environments (INKE). Last modified December 5, 2013. https://drc.usask.ca/projects/archbook/tableofcontents.php.</ref> Additionally, the Table of Contents is only located in Volume II of the book. By placing the Table of Contents with chapters from Volume I and Volume II only in Volume II, the interdependence of the texts is emphasized, with the full understanding of the work being achieved only when the readers engage with both texts continuously and simultaneously. | ||

Nelson, | |||

Secondly, the book has a Table of Chapters, labeled “Table des Chapitres” before the Table of Contents. The Table of Chapters is broken down into two sections - Book I and Book II for each volume. Each section contains the main argument | Secondly, the book has a Table of Chapters, labeled “Table des Chapitres” before the Table of Contents. The Table of Chapters is broken down into two sections - Book I and Book II for each volume. Each section contains the main argument of each chapter of the book. This navigational feature serves multiple purposes. First, it allows the reader to understand the main idea of the book before diving into the detailed content. Second, it provides the reader with an outline of the logical flow of the text offering a roadmap that summarizes the main arguments of the text. Lastly, it allows for the readers to revisit key arguments by quickly locating important discussions. The location of the Table of Chapters only in Volume II further underscores the interconnectedness of both volumes. | ||

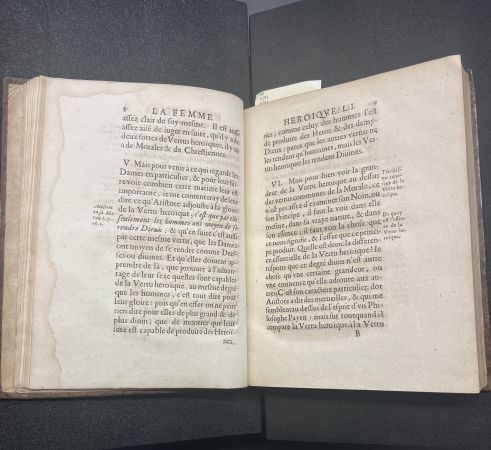

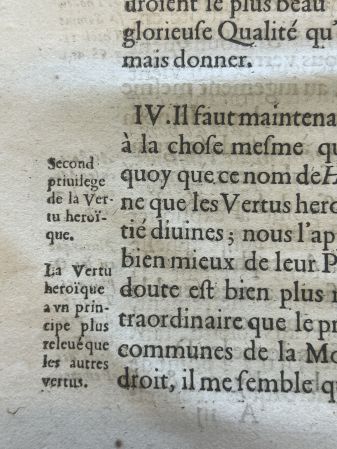

Thirdly, the content in each chapter is broken down into sections with each paragraph assigned a roman numeral. This allows for the reader to process the information of the book in chunks rather than a continuous read like other books. Such a navigational feature aids readers in following the complex arguments presented by Du Bosc in each chapter regarding the equal virtue of men and women, especially given that the text takes on a dense philosophical and religious approach. | Thirdly, the content in each chapter is broken down into sections with each paragraph assigned a roman numeral. This allows for the reader to process the information of the book in chunks rather than a continuous read like other books. Such a navigational feature aids readers in following the complex arguments presented by Du Bosc in each chapter regarding the equal virtue of men and women, especially given that the text takes on a dense philosophical and religious approach. | ||

The book also includes extensive printed marginalia to help the reader navigate through the different points about heroic virtues Du Bosc outlines in each chapter. It is worth noting that during the | The book also includes extensive printed marginalia to help the reader navigate through the different points about heroic virtues Du Bosc outlines in each chapter. It is worth noting that during the this time period printed marginalia was thought to be both useful and counterproductive in Western European texts. On the one hand, marginalia was considered to have several benefits during the printing process. It was useful for making distinctions, translations, interpretations, evaluations and providing clarity for dense texts. <ref name="slights">Slights, William WE. ''Managing readers: printed marginalia in English Renaissance books''. University of Michigan Press, 2001.</ref> On the other hand, many regarded printed marginalia as disruptive to the reading experience with claims that it was irrelevant to the text, “annoyingly coercive” and even an offense “to the eye [and] aesthetics of the text.” <ref name="slights"/> Thus, it is likely that while some readers appreciated the printed marginalia in ''La Femme Heroique'', others believed it detracted from their reading experience. | ||

<gallery mode="packed" heights=300px> | |||

Image:Table of Contents.jpeg|Table of Contents in Volume II of ''La Femme Heroique'' | |||

Image:Table of Chapters.jpg|Table of Chapters in Volume II of ''La Femme Heroique'' | |||

Image:Numbered Sections V and VI.jpeg|Numbered Sections in Volume II of ''La Femme Heroique'' (Sections V and VI) | |||

Image:Printed Marginalia.jpeg|Printed Marginalia in ''La Femme Heroique'' | |||

</gallery> | |||

===Typography=== | ===Typography=== | ||

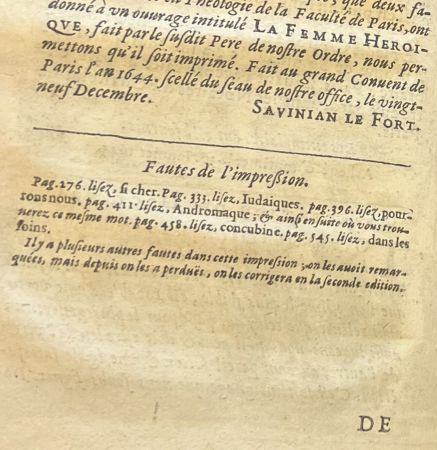

Volumes I and II of ''La Femme Heroique'' include numerous printing mistakes. For example, there are numerous pages with meaningless letters at the bottom, including “ “i i j” or “N n n n i i j” in both volumes. Additionally, there are several instances where similar letters are switched, particularly with the “U” and “V” such as | Volumes I and II of ''La Femme Heroique'' include numerous printing mistakes. For example, there are numerous pages with meaningless letters at the bottom, including “ “i i j” or “N n n n i i j” in both volumes. Additionally, there are several instances where similar letters are switched, particularly with the “U” and “V” such as the words “Brvtvs” and “Conqviesme” in the cover page for Chapter 5 in Volume II, which are supposed be spelled as "Brutus" and "Conquiesme." Lastly, there are incomplete letters due to improper pressing of movable type. This is reflected in incomplete letters like “V” in “ De la Vertev” in the cover page of Chapter 1 in Volume I. Such printing mistakes are explained by the fact that, up until the eighteenth century, European authors were present during the printing process correcting their own work. This often resulted in their work being published with printing errors because authors were “too close to their works to correct them effectively.” <ref name="malone">Malone, Edward A. "Learned correctors as technical editors: Specialization and collaboration in early modern European printing houses." ''Journal of business and technical communication'' 20, no. 4 (2006): 389-424. </ref> That said, European authors during this time period were open to working collaboratively with their readers to correct printing mistakes. For example, authors would request and sometimes compensate readers for pointing out printing mistakes they could correct in future editions, though it is unclear if this was the case with Du Bosc’s ''La Femme Heroique''. <ref name="malone"/> | ||

Importantly, although ''La Femme Heroique'' does not indicate collaboration with readers to address printing mistakes in future editions, it does include an [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erratum errata] list, cautioning the reader of several printing mistakes they will encounter while reading the book. This was a common book feature in seventeenth century Europe. Given rampant printing mistakes in books, authors sometimes offered apologies or long lists of printing corrections at the end of their work. <ref name="malone"/> It is worth noting, however, that the errata list included in ''La Femme Heroique'' is short and does not include all of the printing mistakes aforementioned. The errata list is also only included in Volume 1. | Importantly, although ''La Femme Heroique'' does not indicate collaboration with readers to address printing mistakes in future editions, it does include an [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erratum errata] list, cautioning the reader of several printing mistakes they will encounter while reading the book. This was a common book feature in seventeenth century Europe. Given rampant printing mistakes in books, authors sometimes offered apologies or long lists of printing corrections at the end of their work. <ref name="malone"/> It is worth noting, however, that the errata list included in ''La Femme Heroique'' is short and does not include all of the printing mistakes aforementioned. The errata list is also only included in Volume 1. | ||

<gallery mode="packed" heights=300px> | |||

Image:Random Letters.jpeg|Random Letters at the Bottom of Page in ''La Femme Heroique'' | |||

Image:Switching Letters.jpeg|Switching of the Letter "U" and "V" in "Brutus" spelled in ''La Femme Heroique'' | |||

Image:Incomplete Letters.jpg|Incomplete Letter "V" in ''La Femme Heroique'' (Sections V and VI) | |||

Image:Errata List.jpg|Errata List in Volume I of ''La Femme Heroique'' | |||

</gallery> | |||

[[File:Illustration.jpeg|250px|thumb|right|Set of illustrations in ''La Femme Heroique'']] | |||

=== Illustrations === | |||

''La Femme Heorique'' has multiple elaborate illustrations made through copper engravings - an intaglio printing technique. Importantly, these illustrations come in pairs. Each pair has one illustration of a man as a hero and another of a woman as a heroine with mirrored compositions and similar gestures. <ref> ''Women who ruled: Queens, Goddesses, Amazons in Renaissance and baroque art.'' Ann Arbor, MI: in association with the University of Michigan Museum of Art, 2002.</ref> By portraying a hero and heroine so similarly, these illustrations complement the book’s premise that men and women hold equal virtue. | |||

Because the illustrations were done through the copper engraving process during the seventeenth century, they were likely done by a professional painter rather than goldsmiths as was the case when the practice originated in Germany in the 15th century. <ref>“Copperplate Engraving.” German Prints, accessed May 12, 2024. https://germanprints.ru/reference/techniques/copperplate/index.php?lang=en#:~:text=The%20copperplate%20engraving%20is%20an,the%20surface%20of%20the%20plate.</ref> The book does not specify which French engraver is to be accredited for the illustrations, as prominent French engravers became more widely recognized towards the second half of the seventeenth century and the early eighteenth century. Among these prominent engravers was [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/G%C3%A9rard_Audran Gérard Audran] who is credited for uniting “the use of the graver and the etching point” and [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/G%C3%A9rard_Edelinck Gérard Edelinck] who was the engraver of the highest order during this time period. <ref> Landow, George P. “Copperplate Engraving.” Victorian Web, accessed May 12, 2024. https://victorianweb.org/graphics/kinds/copper.html.</ref> That said, while the engraver in ''La Femme Heroique'' is unknown, the detailed and complex copper engravings offer a glimpse into the period preceding the emergence of more renowned engravers. | |||

==Significance== | ==Significance== | ||

''La Femme Heroique'' is important for several reasons. First, it is significant for its defiance of patriarchal norms of seventeenth century France. Its claim that men and women have equal virtues contributed significantly to the efforts of other feminist writers during this time, such as Marie de Gournay, and set the stage for feminist movements during the eighteenth century. This led to its recognition as one of the greatest feminist literary works in seventeenth century France. Beyond the premise of the book, ''La Femme Heroique'' is significant for its material and aesthetic features. The creative binding with gold tooling and its many navigational features (e.g. Table of Contents, Table of Chapters, Numbered Sections, and Marginalia) emphasize the importance of not only publishing a visually appealing book, but also publishing one that is user-friendly for readers in seventeenth century France. Additionally, the many printing mistakes reveal the significance of the book as an artifact that embodies the history of printing practices in seventeenth-century France. For example, by analyzing the typography in books like ''La Femme Heroique'' | ''La Femme Heroique'' is important for several reasons. First, it is significant for its defiance of patriarchal norms of seventeenth century France. Its claim that men and women have equal virtues contributed significantly to the efforts of other feminist writers during this time, such as Marie de Gournay, and set the stage for feminist movements during the eighteenth century. This led to its recognition as one of the greatest feminist literary works in seventeenth century France. Beyond the premise of the book, ''La Femme Heroique'' is significant for its material and aesthetic features. The creative binding with gold tooling and its many navigational features (e.g. Table of Contents, Table of Chapters, Numbered Sections, and Marginalia) emphasize the importance of not only publishing a visually appealing book, but also publishing one that is user-friendly for readers in seventeenth century France. Additionally, the many printing mistakes reveal the significance of the book as an artifact that embodies the history of printing practices in seventeenth-century France. For example, by analyzing the typography in books like ''La Femme Heroique'' one is able to understand the drawbacks of allowing authors to correct their own work during the printing process. | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

Latest revision as of 20:41, 12 May 2024

Overview

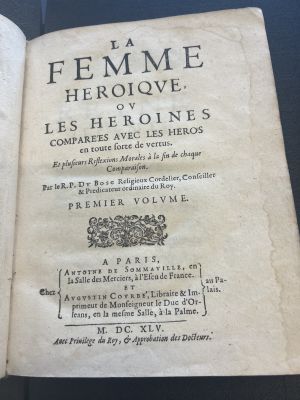

La femme heroique, ou les heroines comparées avec les heros en toute sorte de vertus : Et plusieurs reflexions morales à la fin de chaque comparaison is a two volume French book authored by Jacques Du Bosc. The book was published in 1645 by Antoine de Sommaville in Paris, France and currently resides in the University of Pennsylvania’s Kislak Center for Special Collections. This book is premised on the idea that men and women hold equal virtues. It is considered to be one of the greatest feminist literary works of seventeenth century France.

Background

Historical Context

Importantly, La femme heroique was published in the middle of a crisis and transformation within the book industry in France. After the French Wars of Religion (1562-1598), the economy of France destabilized, heavily impacting the book industry. During this time, there was a lack of books being printed. The Postman of the Plantinian Press Théodore Reinsart testified to this when he said that because of the low supply of books he "could not chase the people out of the room where they were books and sometimes there were as many as 50 people there together.” [1]

Additionally, the few books that were being printed were made with cheaper materials. The book-making industry turned to smaller amounts of gelatin and calcium in the paper making process, thinner paper when publishing books, copper engravings for illustrations instead of wood engravings, and even developed a new book format known as the duodecimo, which saved costs due to its smaller size.[1] On top of the cheaper quality, these books were not being circulated outside of their respective regions due to the economic hardship in France. For example, numerous seventeenth century testimonies corroborate that books published in Paris could not be imported for circulation in other parts of France. [1]

That said, the recovery that followed the collapse of the book industry further into the seventeenth century opened possibilities for previously published works like Du Bosc’s to gain new audiences and recognition as the market stabilized. Among the most notable aspects of France’s recovery in the literary sector was the transition from Lyon to Rouen as the second typographic hub of France in the middle of the seventeenth century. Other cities in France also experienced literary transformations like the city of Troyes, which developed the "blue library." Several cities also adopted the designation "official printer to the king." Printers became conduits for the king's speech and authority, while others formed alliances with local bishops, among other affiliations. [1]

Overall, La femme heroique was published during a transformative period in the literary world of France. While it is likely that the success of the book, like many others, was initially limited due to the economic challenges that plagued the industry, the recovery of the book market would eventually allow it to reach a wider audience. This revival and the evolving dynamics of the literary landscape during the seventeenth century highlight the resilience and adaptability of the book industry in France.

Genre History

The book aligns with other feminist literary works published during the seventeenth century. While French feminism and literature is often linked to the French Revolutionin 1789, writers, both male and female, were publishing important works advocating for equality of the sexes prior to the eighteenth century. In alignment with the book’s focus on moral virtue, other feminist writers during the seventeenth century also advocated for equality with a heavy religious underpinning prior to Du Bosc.

The most renowned of these writers was the French feminist writer Marie de Gouray (1565-1645). In her “Equality for Men and Women (1622)” de Gournay argues that men and women are of equal virtue “only by the authority of God himself and of the Fathers who were buttresses of his Church, and of those great philosophers who have enlightened the universe” (55).[2] Additionally, in her “The Ladies’ Complaint (1626)” De Gournay builds on her religious feminist perspective by outlining the inequality that women in French society experience, which she claims strips women of virtues that men are able to obtain with the privileges they are granted. [2] Du Bosc’s La femme heroique fits well into the religious feminist literary works that were being published during the seventeenth century, setting the stage for the plethora of works that would later be published during the French Revolution in the eighteenth century.

Material Analysis

Binding

La Femme Heroique is bound with a leather calfskin cover with black spots and gold tooling. This was a typical binding method used in France during the seventeenth century, as exemplified by other important works published in Paris during this time period like Traité de la comedie et des spectacles : selon la tradition de l'église, tirée des conciles & des saints pères. [3] In La Femme Heroique, gold tooling is used to draw decorative lines on the covers of each volume as well as to separate the spine of the book into six sections. The second section on the spine in each volume includes the name of the book, “LA FEMME HEROIQUE”, in gold and the third section includes the volume of the book, either “TO.I” or “TO.II.” The remaining sections on the spine use gold tooling to create a flower-like design. Such a creative bookbinding aligns with seventeenth century efforts in France to make the binding process rich and beautiful. [4]

As was customary during the seventeenth century, the gold tooling for this book was specifically done by a skillful person with several years of experience. This is because gold tooling was a complex process that could easily damage the book or fail if the individual did not have an understanding of the right amount of heat to add to each type of leathered cover. For example, if the heat applied was too hot for a particular leather, the impression would burn the cover of the book. If the heat applied was too cold, the gold would not stick onto the cover, and the gold tooling process would fail. [4] Given that the gold tooling on La femme heroique, whether it be the title on the spine of the book or on the decorative lines on the front and back covers, remains intact with no signs of burns, we know that the book was bound by an experienced and skillful person in the book industry during the seventeenth century.

-

Leather Calfskin Cover of La Femme Heroique

-

Gold Tooling on Side of La Femme Heroique

La Femme Heroique has several navigational features. First, it has a Table of Contents, labeled “Table de Matieres” to help the readers navigate the lengthy 300+ page two volume book. The Table of Contents is placed at the end of the book, as is common practice in French books. [5] Additionally, the Table of Contents is only located in Volume II of the book. By placing the Table of Contents with chapters from Volume I and Volume II only in Volume II, the interdependence of the texts is emphasized, with the full understanding of the work being achieved only when the readers engage with both texts continuously and simultaneously.

Secondly, the book has a Table of Chapters, labeled “Table des Chapitres” before the Table of Contents. The Table of Chapters is broken down into two sections - Book I and Book II for each volume. Each section contains the main argument of each chapter of the book. This navigational feature serves multiple purposes. First, it allows the reader to understand the main idea of the book before diving into the detailed content. Second, it provides the reader with an outline of the logical flow of the text offering a roadmap that summarizes the main arguments of the text. Lastly, it allows for the readers to revisit key arguments by quickly locating important discussions. The location of the Table of Chapters only in Volume II further underscores the interconnectedness of both volumes.

Thirdly, the content in each chapter is broken down into sections with each paragraph assigned a roman numeral. This allows for the reader to process the information of the book in chunks rather than a continuous read like other books. Such a navigational feature aids readers in following the complex arguments presented by Du Bosc in each chapter regarding the equal virtue of men and women, especially given that the text takes on a dense philosophical and religious approach.

The book also includes extensive printed marginalia to help the reader navigate through the different points about heroic virtues Du Bosc outlines in each chapter. It is worth noting that during the this time period printed marginalia was thought to be both useful and counterproductive in Western European texts. On the one hand, marginalia was considered to have several benefits during the printing process. It was useful for making distinctions, translations, interpretations, evaluations and providing clarity for dense texts. [6] On the other hand, many regarded printed marginalia as disruptive to the reading experience with claims that it was irrelevant to the text, “annoyingly coercive” and even an offense “to the eye [and] aesthetics of the text.” [6] Thus, it is likely that while some readers appreciated the printed marginalia in La Femme Heroique, others believed it detracted from their reading experience.

-

Table of Contents in Volume II of La Femme Heroique

-

Table of Chapters in Volume II of La Femme Heroique

-

Numbered Sections in Volume II of La Femme Heroique (Sections V and VI)

-

Printed Marginalia in La Femme Heroique

Typography

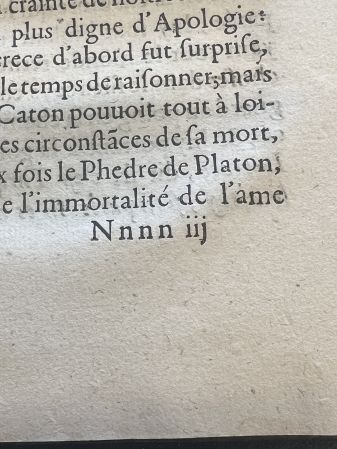

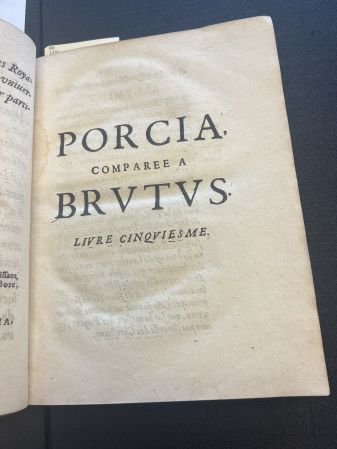

Volumes I and II of La Femme Heroique include numerous printing mistakes. For example, there are numerous pages with meaningless letters at the bottom, including “ “i i j” or “N n n n i i j” in both volumes. Additionally, there are several instances where similar letters are switched, particularly with the “U” and “V” such as the words “Brvtvs” and “Conqviesme” in the cover page for Chapter 5 in Volume II, which are supposed be spelled as "Brutus" and "Conquiesme." Lastly, there are incomplete letters due to improper pressing of movable type. This is reflected in incomplete letters like “V” in “ De la Vertev” in the cover page of Chapter 1 in Volume I. Such printing mistakes are explained by the fact that, up until the eighteenth century, European authors were present during the printing process correcting their own work. This often resulted in their work being published with printing errors because authors were “too close to their works to correct them effectively.” [7] That said, European authors during this time period were open to working collaboratively with their readers to correct printing mistakes. For example, authors would request and sometimes compensate readers for pointing out printing mistakes they could correct in future editions, though it is unclear if this was the case with Du Bosc’s La Femme Heroique. [7]

Importantly, although La Femme Heroique does not indicate collaboration with readers to address printing mistakes in future editions, it does include an errata list, cautioning the reader of several printing mistakes they will encounter while reading the book. This was a common book feature in seventeenth century Europe. Given rampant printing mistakes in books, authors sometimes offered apologies or long lists of printing corrections at the end of their work. [7] It is worth noting, however, that the errata list included in La Femme Heroique is short and does not include all of the printing mistakes aforementioned. The errata list is also only included in Volume 1.

-

Random Letters at the Bottom of Page in La Femme Heroique

-

Switching of the Letter "U" and "V" in "Brutus" spelled in La Femme Heroique

-

Incomplete Letter "V" in La Femme Heroique (Sections V and VI)

-

Errata List in Volume I of La Femme Heroique

Illustrations

La Femme Heorique has multiple elaborate illustrations made through copper engravings - an intaglio printing technique. Importantly, these illustrations come in pairs. Each pair has one illustration of a man as a hero and another of a woman as a heroine with mirrored compositions and similar gestures. [8] By portraying a hero and heroine so similarly, these illustrations complement the book’s premise that men and women hold equal virtue.

Because the illustrations were done through the copper engraving process during the seventeenth century, they were likely done by a professional painter rather than goldsmiths as was the case when the practice originated in Germany in the 15th century. [9] The book does not specify which French engraver is to be accredited for the illustrations, as prominent French engravers became more widely recognized towards the second half of the seventeenth century and the early eighteenth century. Among these prominent engravers was Gérard Audran who is credited for uniting “the use of the graver and the etching point” and Gérard Edelinck who was the engraver of the highest order during this time period. [10] That said, while the engraver in La Femme Heroique is unknown, the detailed and complex copper engravings offer a glimpse into the period preceding the emergence of more renowned engravers.

Significance

La Femme Heroique is important for several reasons. First, it is significant for its defiance of patriarchal norms of seventeenth century France. Its claim that men and women have equal virtues contributed significantly to the efforts of other feminist writers during this time, such as Marie de Gournay, and set the stage for feminist movements during the eighteenth century. This led to its recognition as one of the greatest feminist literary works in seventeenth century France. Beyond the premise of the book, La Femme Heroique is significant for its material and aesthetic features. The creative binding with gold tooling and its many navigational features (e.g. Table of Contents, Table of Chapters, Numbered Sections, and Marginalia) emphasize the importance of not only publishing a visually appealing book, but also publishing one that is user-friendly for readers in seventeenth century France. Additionally, the many printing mistakes reveal the significance of the book as an artifact that embodies the history of printing practices in seventeenth-century France. For example, by analyzing the typography in books like La Femme Heroique one is able to understand the drawbacks of allowing authors to correct their own work during the printing process.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Walsby, Malcolm. "Les étapes du développement du marché du livre imprimé en France du XVe au début du XVIIe siècle." Revue dhistoire moderne contemporaine 673, no. 3 (2020): 5-29.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Desmond, M. Equality of the Sexes-Three Feminist Texts of the Seventeenth Century. Oxford University Press, 2013.

- ↑ “17th century: Refinement in style.” Michigan State University Libraries. https://lib.msu.edu/exhibits/historyofbinding/17thcentury

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Diehl, Edith. Bookbinding: its background and technique. Courier Corporation, 2013.

- ↑ Nelson, Brent. "Table of Contents." Implementing New Knowledge Environments (INKE). Last modified December 5, 2013. https://drc.usask.ca/projects/archbook/tableofcontents.php.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Slights, William WE. Managing readers: printed marginalia in English Renaissance books. University of Michigan Press, 2001.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Malone, Edward A. "Learned correctors as technical editors: Specialization and collaboration in early modern European printing houses." Journal of business and technical communication 20, no. 4 (2006): 389-424.

- ↑ Women who ruled: Queens, Goddesses, Amazons in Renaissance and baroque art. Ann Arbor, MI: in association with the University of Michigan Museum of Art, 2002.

- ↑ “Copperplate Engraving.” German Prints, accessed May 12, 2024. https://germanprints.ru/reference/techniques/copperplate/index.php?lang=en#:~:text=The%20copperplate%20engraving%20is%20an,the%20surface%20of%20the%20plate.

- ↑ Landow, George P. “Copperplate Engraving.” Victorian Web, accessed May 12, 2024. https://victorianweb.org/graphics/kinds/copper.html.