A course of chirurgical operations, demonstrated in the Royal Garden at Paris / by Monsieur Dionis ... ; translated from the Paris edition.: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 97: | Line 97: | ||

The octavo format allows this textbook to be smaller than folio books, which could make it cheaper and more accessible. Another potential benefit of the smaller format is that surgeons can carry and use a more compact book in the surgery room than a bulkier folio book. | The octavo format allows this textbook to be smaller than folio books, which could make it cheaper and more accessible. Another potential benefit of the smaller format is that surgeons can carry and use a more compact book in the surgery room than a bulkier folio book. | ||

<br clear=all> | <br clear=all> | ||

[[File:PT BindingSpineView.jpeg|right| | [[File:PT BindingSpineView.jpeg|right|75px|thumb|Spine of this copy]] | ||

[[File:PT FrontCover.jpeg|left|125px|thumb|Binding on the front cover of this copy]] | [[File:PT FrontCover.jpeg|left|125px|thumb|Binding on the front cover of this copy]] | ||

=== Binding === | === Binding === | ||

Latest revision as of 01:49, 28 March 2024

Introduction

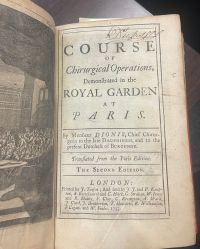

Initially written in French, A Course of Chirurgical Operations, Demonstrated in the Royal Garden at Paris was a transformational medical textbook published in 1707, at the cusp of the transition from medieval to modern-day surgical medicine. Authored by French writer and surgeon Pierre Dionis, the original French book was called Cours d'operations de Chirurgie. It would become very popular nationally and internationally, leading to many editions and translations.

The book provides a detailed description of surgeries that Monsieur Dionis demonstrated at the Jardin Royal in Paris. It is well organized, with each chapter discussing a specific condition and its treatment and a complete description of how to perform the surgery, including images of the tools and anatomical modifications used. He wrote the book to spread knowledge of these specific surgical techniques all over France and eventually the world to improve the general state of medicine and the quality of medical care in Europe.

This specific copy is the English translation of the second edition of Pierre Dionis’s textbook and was published in 1733. It is titled A Course of Chirurgical Operations, demonstrated in the Royal Garden at Paris by Monsieur Dionis ...; translated from the Paris edition and can be found in the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts at the University of Pennsylvania. This textbook helped transform surgical practices all over Europe in the 18th century and set the foundation for the modern state of surgery.

Historical Context

Understanding the state of surgery and medicine before and around Pierre Dionis’s lifetime is crucial for understanding his prominent influences and lasting impact.

Medicine and Surgery - Middle Ages to the 17th Century

The surgical specialty was not respected until after the 17th century due to its poor reputation during Medieval times and the prevailing preference for educated physicians over invasive surgeons.

Medicine was primarily based on traditional Greek medical ideology during the Middle Ages. One of the strongest influences on Medieval medicine was the teachings of the 2nd-century Greek physician Galen.[1] His method of practicing medicine, the Galenic system, was based on theory rather than practical evidence, leading to many flaws in patient care. One of his most prevailing, albeit progress-impeding, theories was his revision of the ancient Greek humoral theory, which posited that the body has four humors (black bile, phlegm, blood, and yellow bile), and an imbalance in any of these humors was the cause of changes in health and behavior.[1] The Galenic-based focus of medicine during the Middle Ages and into the 17th century led to conflicts between the divisions of medical practitioners, particularly physicians and surgeons.[2] Since a theory-based practice was heavily preferred during this period, the public respected general physicians who underwent formal theory-based education. On the other hand, surgery was seen as being inferior because it was more practical and hands-on and seemed barbaric and a last resort.

The field of surgery was emerging more widely beginning in the 16th century, and the "surgeons" during this time were often barbers who also performed surgery and were called "barber-surgeons".[3] Most of them were not formally trained, and they applied Galenic ideology to their treatments, which hindered their understanding of the body. Since the focus was on balancing bodily fluids as the primary treatment method, invasive procedures were not prioritized, which led to an inadequate understanding of internal anatomy and sub-optimal practices.[1]

One of the biggest focuses of the surgeons was reducing pain because they believed pain results from humoral imbalances.[4] To minimize the time pain is felt and reduce the risk of uncontrolled bleeding, surgeons prioritized speed in their surgeries rather than accuracy. However, this led to an extremely high rate of complications -such as a slower rate of healing and increased rate of infection- that further stained the reputation of surgery.[4]

Unfortunately, due to the high error rate of surgery in the Middle Ages and beyond, as well as various widespread public health issues during the Middle Ages (such as the Black Death), the field of surgery had a long-lasting stained reputation, and European society continued to favor religious, medical theories over scientific ones.[1]

Evolution of Surgery Into the 18th Century

The Renaissance was pivotal in prompting a new way of approaching medicine and viewing surgery. However, due to the prevailing Galenic-based ideology, it was not until the 18th century that there was a widespread transformation in the medical approach, and surgeons finally elevated their status in the medical field.[3]

During the Renaissance, a notable trailblazer for transforming surgical practice was a 16th-century French barber surgeon named Ambroise Paré. Though a barber-surgeon, he was one of the first to pioneer an empirical method of surgical practice.[5] While surgeons at the time thought quick but painful surgeries were optimal, Ambroise was able to devise surgical techniques that allowed him to take more time on his surgeries while also minimizing the pain felt by patients. He developed practical techniques to minimize tissue damage, reduce blood loss, and prevent infections, among other improvements.[5] He inspired a new wave of evidence-based surgery.

In the 17th century, surgeons began to focus more on their own academic achievement and specialized set of skills. A notable discovery in the mid-17th century that spurred massive changes was surgeon William Harvey’s revolutionary description of blood circulation that opposed the ancient Galenic theories about circulation.[6] This new theory gave surgeons a more accurate representation of human anatomy and proved the importance of practicing medicine using deductive reasoning, logic, and experimentation rather than ancient Greek theories. Harvery's contribution helped address the long standing problem of uncontrolled bleeding in surgery, allowing surgeons to take more time while performing surgery and reducing the complication rate.[6]

However, these evidence-based practices were still widely unpopular in Europe until many factors increased the appreciation for adept surgeons. A crucial factor was a greater need for specialized surgeons in England towards the end of the 17th century.[2] With developments in trade, the British empire expanded, and thus, they needed more specialized surgeons to maintain workers' health, which was vital in expanding their political reach. For trade, for example, competent ship surgeons were essential to ensure the health of British tradespeople on ships. For war, expert military surgeons were crucial for supporting the army's health as they became involved in more wars.[2] With the increasing importance of surgery, higher standards were being placed on surgeons, and it became harder to be both a Barber and a surgeon.

Throughout the 18th century, there were many more examples of how evidence-based surgical practices allowed for much better outcomes than the Galenic methodology. The improvement of standards for patient care and successful outcomes led to an increase in public approval of such practices and further encouragement for developing specialized surgical training institutions. In England, the distinction between Barbers and Surgeons was legally defined in 1745 when the English government enforced an act of parliament that divided the Company of Barber Surgeons into two separate bodies.[7] Finally, in 1800, a Royal Charter officially created ‘The Royal College of Surgeons in London’, marking one of the first of many such schools specializing in surgery developing in Europe.[7]

The transformational steps taken in the 17th and 18th centuries allowed for a much wider adoption of evidence-based practices, creating the foundation for modern medicine and surgical practices.

Pierre Dionis

Born in 1643 in Paris, Pierre Dionis spent his lifetime dedicated to his profession as a French Surgeon and Anatomist.[3] He would become one of the most influential leaders in the field of surgery. Not much is known about his childhood, but he was known to have always had an interest in medicine. He would go on to study surgery in “Confrérie de Saint-Côme et de Saint-Damien,” the Paris Guild of Surgeons.[3] Once he completed his training, he started as a French army surgeon.[3] In 1672, Dionis was appointed by King Louis XIV to work as a surgeon at the Jardin des Plantes (the botanical garden, or royal garden) and was tasked with performing surgical and anatomic demonstrations at the Royal Garden.[3] The Royal Garden was an institution that was founded by King Louis XIII in order to teach the latest medical science. Dionis’s appointment to this role is a testament to the adept surgical skills he obtained and his strong reputation. Dionis later attained the even more prestigious title of chief court surgeon in 1685, highlighting the king’s ultimate trust in his abilities.[3] He continued as the surgeon to the royal family. While acting as the chief court surgeon, he also was a surgical professor at the Collège de Médecine in Paris.[3]

Throughout his lifetime, Dionis wrote many influential medical books on surgery and beyond, with his magnum opus being A Course of Chirurgical Operations, demonstrated in the Royal Garden at Paris.[3] Unlike many other medical professionals during his time, Dionis was a staunch advocate of groundbreaking ideas that would be widely accepted in future centuries. For example, he vehemently pushed against the Galenic theory of circulation in favor of Harvey's theory. One of his most significant contributions to surgery is how he pushed for using pain relieving techniques when other surgeons at the time believed it was not necessary or futile.[3] His push for pain relief and experimentation with different chemicals and techniques to achieve this would lay the foundation for the invention and adoption of anesthesia in the 19th century.[3]

As a result of his lifelong dedication to spreading his advanced medical and surgical knowledge, he helped push France ahead of Europe regarding surgical practices, and he contributed to significant advancements in the field in the 18th century.[3]

Understanding the Book

Book Content and Organization

Content Overview

“A Course of Chirurgical Operations, Demonstrated in the Royal Garden at Paris/ translated from the Paris edition” presents in-depth information about ten separate demonstrations that Pierre Dionis did in the Royal Garden. The book's title page provides information about this specific copy’s publisher, J. Tonson, publishing location, London, and provides many additional credits to key contributors to creating this book.

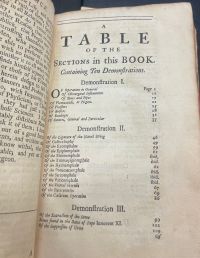

The titles of the first few chapters can be seen in the image of the table of contents. The first chapter, Demonstration 1, provides a general overview of surgical methodology and instructions, with subheadings such as “Of Operations in General.” This is similar to a modern-day textbook's general introduction chapter. The other nine demonstrations seem varied in their breadth and depth of content coverage. For example, sections such as Demonstration III, “Of the Extraction of the Stone,” focused on demonstrations with a particular surgical topic focus, while other sections, such as Demonstration VIII, “Of bleeding, and all that belongs to it,” cover a broad array of techniques under a more general topic.

By having a general chapter at the beginning, followed by clearly organized chapters around various topics, it is clear that Pierre aimed to make this book educational and as comprehensive as possible to convey all of his knowledge to other aspiring surgeons. The specific content and navigational features discussed in the following sections further indicate Pierre’s dedication to increasing the content’s accessibility for readers.

The book's table of contents gives a comprehensive overview of all the chapters and their subheadings, emphasizing the robust organization between different parts of the book. The well-thought-out navigational features are further evident with the defined title page at the beginning of each new chapter, effectively marking the end of the previous section and the start of the next.

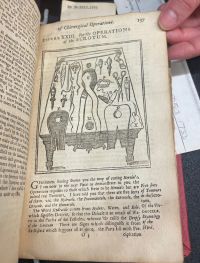

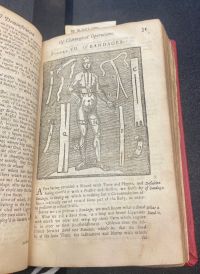

The title pages have a consistent imagery format, with the decorative woodcut and heading font text, as seen in the image to the right of the Fourth Demonstration chapter. Each chapter also has an engraved plate image of the surgical instruments used in the procedures discussed in that chapter, as seen in the images section. These features provide the reader with a clear indication that they are in a new section and a general understanding of what instruments and procedure types they can expect in the rest of the section.

Once past the title page, the content within the chapters is divided into further subdivisions, such as descriptive subheadings, which help organize the chapter's content into organized subsections. This is seen in the image of a page within the Fourth demonstration chapter, where a subheading says “manner of curing Hernia’s” in large, indented, centered, and spaced text that indicates the topic of the new section within that chapter.

The pages within each chapter provide clear markers of relative location in the book. One example is how the pages have page numbers at the top corners. Another example is how for all pages within the chapter, the top of the left page has a heading indicating the specific demonstration (the specific section heading/chapter) you are currently in, and the top of the right page says “of churgical operations.” These markers help the reader quickly understand which section they are in and the relative location within the book regarding page number without having to flip back to the title page or the table of contents.

Printed Marginalia

The only handwritten marginalia in the book appears to be the ownership mark on the title page (the signature in the top right-hand corner).

However, there is ample printed marginalia throughout the book that Pierre Dionis authored. The printed marginalia appear to give quick descriptions of the paragraph's focus. Monsieur Dionis likely included the printed marginalia to ensure readers can absorb his key takeaways. The printed marginalia could help clarify complex medical topics, guide the reader through the key points, reinforce crucial information, and provide quick access to knowledge, among many other benefits.

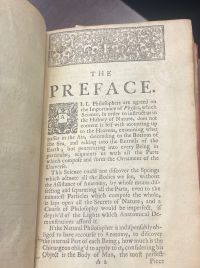

Paratexts

The preface is a direct translation of the original preface written by Pierre Dionis (it is something other than what the translator added). It gives background about the author and the importance of surgical teaching and describes the organizational structure of the information presented in the book. He emphasizes the importance of science and medicine and strongly advocates for people to be exposed to this knowledge. The preface's content suggests that the textbook's primary audience included doctors, surgeons, and medical students during the period. However, Pierre also hopes that anyone in the general public interested in this information will read it. The preface also explains the structure of the book, talking about the focus of each chapter, with many chapters dedicated to a unique demonstration that he did, and he is writing about it so that people who did not witness the procedure can learn about it.

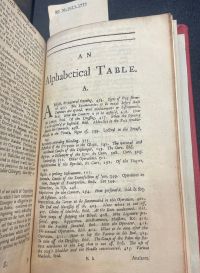

At the book's end is a section called "An Alphabetical Table," which is the modern-day equivalent of an index. This index is the English translation of Pierre Dionis’s original index section. Similar to the purpose of a modern-day index, this section provides a list of key terms discussed in the book in alphabetical order and the pages they are found on. It even includes the sentences each term is a part of.

Illustrations

Woodcut imagery is used at the beginning of each section, as seen in the image of the Preface, which improves the aesthetics of the chapters while emphasizing the beginning of a new section, both of which improve the reading experience.

Additionally, the book contains many illustrations to enhance readers' understanding, with descriptive visuals supplementing the content in the chapters. The beginning of each chapter generally has an image of the tools used in that surgery, as seen in the engraved plate image on the right. These images are sometimes engraved plate images. Each instrument in the pictures is labeled with letters referred to within the text so that the author can explain all of the image features in great detail. There are also more images throughout the chapter that help clarify complex topics, such as images that provide anatomical representations of the body, where each tool will be used on the body, and what happens with each described procedure.

Material Features

Substrate

The book's substrate is handmade paper, as evidenced by the chain lines seen when light shines underneath the page.

The pages show some signs of aging and wear and tear, such as brown spots, creases, wrinkles, and minor tears on many pages throughout the book. They also show signs of yellowing and darkening, as seen in the side view. However, given the book's age, the imperfections are much less severe than would be expected if it was circulated among many people and treated without care.

The remarkable condition of this copy's pages indicates that the book may have been in circulation for a short period with limited owners before it was stored somewhere like a library. The lack of handwritten marginalia (except for the one discussed instance) further supports this kind of ownership. It may indicate that it was likely mostly owned by libraries, such as medical school libraries, and checked out by others as needed.

Format

The book has 496 pages and nine unnumbered leaves of plates that are likely meant for notes. It is structured as a codex with an octavo format, which means it is assembled with multiples of 8 pages per gathering. The letters at the bottom of the page in the center are signature marks; they are only present on half of the pages in each gathering because the second one is part of the bifolium.

The octavo format allows this textbook to be smaller than folio books, which could make it cheaper and more accessible. Another potential benefit of the smaller format is that surgeons can carry and use a more compact book in the surgery room than a bulkier folio book.

Binding

The binding seems to be rebounded with newer material and is in excellent condition, with no signs of fading or damage. Additionally, some contemporary pages precede and follow the pages from the initial book. Both signs indicate that the University of Pennsylvania library rebounded the book upon acquisition and added the extra pages during the binding process.

The binding is a thick hardcover with a bumpy texture, likely meant to preserve the integrity of the pages and protect them from external damage while also providing extra grip for those using it. The cover's design is simple: primarily plain red except for the gold text on the spine with the title, author, and name of the library at Penn that rebounded the book.

Historical Significance

A Course of Chirurgical Operations, demonstrated in the Royal Garden at Paris is a significant work in the history of medicine that stands as an example of Europe’s switch from its ancient medical practices to those based more on evidence and reason. This book played an influential role in shaping modern-day medicine and surgery. As mentioned in the historical context section, it was not until the end of the 18th century that the surgical discipline truly separated from its association with barbers and adopted an evidence-based approach to medical practice. This textbook played a pivotal role in this process, as can be seen with how the first edition was published in 1707, and this second edition translated copy was published in 1733, reflecting the increasing desire across Europe to adopt this new surgical practice.

The popularity and influence of this book’s content are evident with the extensive measures publishers took to adapt and spread this knowledge. The fact that this copy is an English translation and a second edition of the original book shows that the original book had enough universal acclaim to make it worth expanding the textbook to new languages and spreading it to countries beyond France. Though Pierre died shortly after publishing the first edition in French, his legacy appears to have only grown more robust in the decades after his death, as indicated by this second edition copy being published in 1733, 15 years after he died in 1718.

As mentioned previously, Pierre Dionis was a staunch advocate of practical, evidence-based medical practices, which is clearly evident in his creation of this textbook, which provides a detailed account of different surgeries he conducted and his thoughts on them. Rather than writing a textbook about applying ancient Greek ideologies and theories to surgery, he made a very practically based textbook. His inspiration from other forward thinkers around his time is very evident in the design of his book, such as how he adopted his predecessor, French barber-surgeon Ambroise Paré's inclusion of imagery of surgical tools at a time when there were not many surgical books with imagery. He also includes information about surgical techniques and methodology developed by previous revolutionary surgeons, such as Harvery’s methods for reducing blood loss with ligatures. He also developed many novel, evidence-based techniques, which he included in this book. The evident popularity of the textbook further indicates how he was the primary expert in such knowledge and was providing information that not many others had seen before.

Ultimately, this textbook is a testament to Pierre’s skill as a surgeon and his commitment to sharing his knowledge and educating others. Monsieur Dionis's teachings through this textbook played a pivotal role in raising the standards for surgical education and practice in 18th-century Europe, and the impact of this textbook is evident in surgery and medicine today.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Hajar, Rachel. "The Air of History (Part II) Medicine in the Middle Ages." Heart views : the official journal of the Gulf Heart Association vol. 13,4 (2012): 158-62. doi:10.4103/1995-705X.105744

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Barry, Jonathan. "John Houghton and Medical Practice in London c. 1700." Bulletin of the History of Medicine, vol. 92 no. 4, 2018, p. 575-603. Project MUSE, https://doi.org/10.1353/bhm.2018.0072.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 Tubbs, R Shane et al. "Pierre Dionis (1643-1718): surgeon and anatomist." Singapore medical journal vol. 50,4 (2009): 447-9.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Walker, Katherine A. "Pain and Surgery in England, circa 1620-circa 1740." Medical History vol. 59,2 (2015): 255-74. doi:10.1017/mdh.2015.2

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Drucker, Charles B. "Ambroise Paré and the birth of the gentle art of surgery." The Yale journal of biology and medicine vol. 81,4 (2008): 199-202.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Aird, William. “William Harvey on The Blood • The Blood Project.” The Blood Project, 16 Jan. 2023, www.thebloodproject.com/william-harvey-on-the-blood/.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Royal College of Surgeons. "History of the RCS." Royal College of Surgeons, www.rcseng.ac.uk/about-the-rcs/history-of-the-rcs/#:~:text=In%201745%2C%20the%20Barber%2DSurgeons,the%20bodies%20of%20executed%20criminals. Accessed 18 Jan. 2024.