Grand Musical Staircase

Introduction

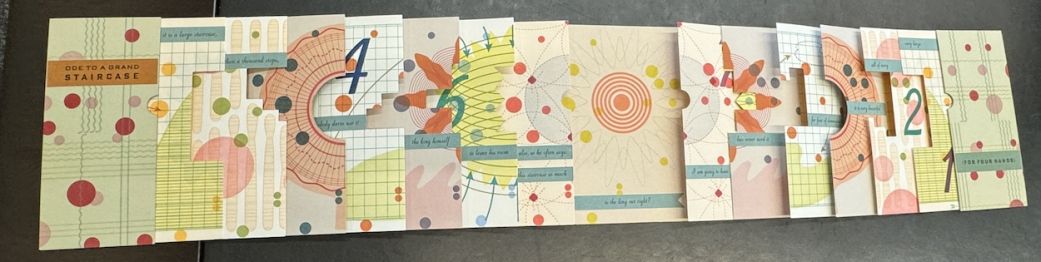

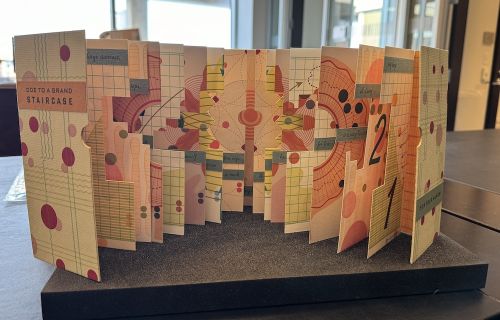

Julie Chen and Barbara Tetenbaum’s “Ode to a Grand Staircase (For Four Hands)” is an artist’s book inspired by the work of Erik Satie, a French composer whose work influenced early twentieth-century music. [1] This artist’s book was published in 2001 by the Flying Fish Press (Berkeley, CA) via Julie Chen [2] and the Triangular Press (Portland, Oregon) via Barbara Tetenbaum. [3] The artists’ book is a multi-layered visual narrative inspired by Erik Satie’s music, specifically “Marche du Grand Escalier” (March of the Grand Staircase), composed in 1914. The book can be rearranged into an accordion-like shape representing a grand staircase. Colorful images and cut-outs comprise the book’s pages, as well as text taken from “Marche du Grand Escalier” that Satie included in his scores. [4] Penn Libraries acquired copy number 69 of this artists’ book via the Amy Comegys Memorial Fund and the Ruth and Marvin Sackner Fund for the Arts of the Contemporary Book Collections. [4] The book is located in the Kislak Center for Special Collections at the University of Pennsylvania.

About the Authors

Julie Chen

Julie Chen is an Asian American book artist and educator from California who established the Flying Fish Press in 1987 while she was a graduate student studying Book Art at Mills College in Oakland, California. She publishes her work via this imprint in small editions which are displayed in museums and libraries all around the world, including the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Museum of Modern Art. [6] Julie conducts extensive research about certain topics, people or regions before designing her artists’ books. She uses letterpress printed images and cards to assemble her books, and usually designs a box covering for each work. She started making these books when she was in her mid-twenties, and describes the book-making process as constantly having many different moving parts in progress that eventually come together as one unified piece. [7] Her artists’ books do not have much separation between structure and content. She has collaborated with other artists such as Barbara Tetenbaum and Lois Morrison. She teaches Book Art at Mills College in Oakland, California. [7]

Barbara Tetenbaum

Barbara Tetenbaum is a visual artist who explores reading through print, animation and installation. She founded the Triangular Press in 1979 to publish her works and has received two Fulbright Fellowships and other career rewards. For 25 years she led the Book and Print Department at Oregon College of Art and Craft and is now a Visiting Professor of Studio Art at Reed College. [9]

Artists’ Books

"Ode to a Grand Staircase (For Four Hands)" is an artist's book, which is unlike any of the books we would normally read today – they vary vastly in format and many are not meant to or cannot be read in a conventional textbook-style manner (from left to right). Artists have enhanced texts by adding decorative elements and illustrations throughout history. The introduction of the printing press is what made the evolution of illustrative formats such as woodcuts and engravings possible, and the mass production of books began. [10] In the early twentieth century in France, the illustrated book reached its height with printed illustrations by famous artists like Picasso. [10] The modern artists’ book genre took these concepts and “manipulate[d] the book into a work of art that conveys an idea in a visual and tactile format.” [10]

Jessica Pigza, Associate Director of the Yale Special Collections and Public Programs in the Arts Library, states that the first forerunner to this genre was British poet, printmaker and painter William Blake (late 1700s – early 1800s). [11] Although he did produce books in the traditional format, he aimed to integrate the text and visuals on every page like book artists today, and accomplished this by developing a new printing method. Like the book artists of the 1960s, Blake “seek[ed] a means of bringing the production of illustrated texts under his own control so that he could become his own publisher, independent of commercial publishers and letterpress printers.” [11] This change in the author also being the publisher and printer was very significant in the history of book-making and printing, as this tended to remain separate at the time. It can be seen today that book artists like Julie Chen and Barbara Tetenbaum establish their own presses to publish their works – for example, “Ode to a Grand Staircase” was both created and published by the authors via the Flying Fish Press and the Triangular Press.

Pigza mentions that Blake is sometimes overlooked in the discussion of the history of modern artists’ books. Instead, the first mention of the integration of visual arts in a book format is from France in the 1890s, where Ambroise Vollard, a Parisian art dealer, “use[d] … the book format to showcase the work of an artist, the livre d’artiste.” [11] These works still contained the “standard distinction of image and text,” although they did not fit the genre of artists’ books we have today. [11] Starting in the 1910s, Russian Futurists started to “mak[e] books as art, in much the same spirit of the 1960’s in America.” [11] The Italian Futurist movement of the 1910s and the German Bauhaus movement of the 1920s-30s were integral in using typography to help merge text and image together. [11] Many photographic books emerged in the German New Realism movement, and the “ethical and political concern for the function of art in society” from the European Dada movement (1910s-1920s) set the foundation for the idea underlying modern artists’ books in the 1960s. [11] The modern notion of artists’ books took form Post-WWII in Europe and in 1960’s America. [11] New technological advances also helped streamline book production, building upon the notion of a “‘democratic’ form of art, with complete control over production and distribution.” [11]

Like other artists’ books today, “Ode to a Grand Staircase” draws upon these new technological advances that have allowed for its creation, publication and dissemination, all by the authors themselves, a contrast from how printing and publishing first operated. [4]

Inspiration from Erik Satie

Erik Satie was a French composer in the late 1800s and early 1900s. [13] He studied at the Paris Conservatory for a short while and then studied at Schola Cantorum. [13] His work is tied to the Dada and Surrealist artistic movements and “disregards traditional forms and tonal structures,” much like how artists’ books defy the traditional book form. [13]

“Ode to a Grand Staircase” was inspired by Satie’s works, and the text throughout the artists’ book “is derived from the musical directives and silent librettos” throughout his scores. [4] The story itself is from Satie’s “Marche du Grand Escalier,” which can be listened to via this video, which contains the corresponding sheet music. The song itself very much resembles the back-and-forth movement of a march up and down a staircase with the repeated pattern of notes of different intervals ascending and descending on the piano keys.

Satie’s music can be listened to via the University of Pennsylvania’s Naxos Music Library, where the eccentricity and “avant-garde … fusion of art and life” are extremely apparent in his Trois Gymnopédies. [14] His differing style of music during his time reflects Chen and Tetenbaum’s own artists’ books, representing a whole different genre of communicating and presenting subject matter in completely new formats.

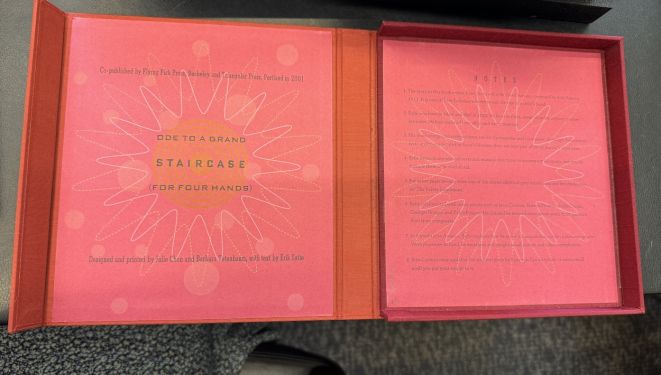

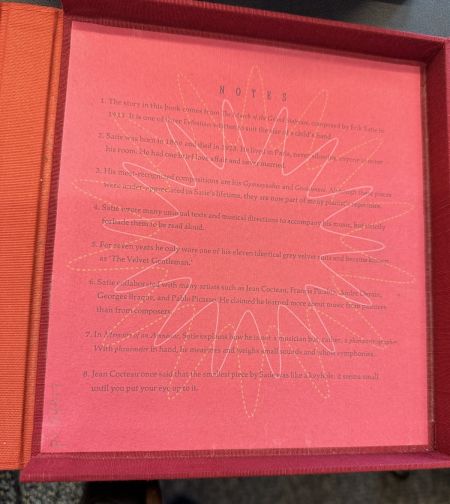

On the inside of the red cloth-covered box the artists’ book is stored in, the authors list 8 facts about Satie as a tribute to his inspiration. They include his most accomplished works (his ‘’Gymnopaedies’’ and ‘’Gnossiennes’’) and details about how he lived, including the fact that he never let anyone enter his room and that he had one love affair in his life. They also mention that he “wrote many unusual texts and musical directions to accompany his music, but strictly forbade them to be read aloud,” and these musical directives are included within “Ode to a Grand Staircase.” [4]

Content and Structure

Substrate

This artists’ book comes in a red cloth-covered box with a magnetic closure, which opens up to what might be considered a title page on the left and notes on the right about Erik Satie, who inspired the creation of this book.

-

Top of box cover

-

Inside of box cover

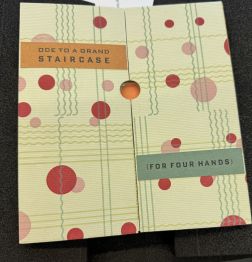

The artists’ book itself is made of box lining paper and “letterpress printed cut card panels attached to concertinas on both sides [of the book] creating two spines.” [15] These materials are different from the paper used for regular books today or the parchment and papyrus substrates we have studied in class from the past. Chen and Tetenbaum are using different artistic techniques to assemble a book as an art piece, and they are the ones that are designing, printing and putting together every single copy.

-

Front of artists’ book

-

Artists’ book unfolded, showing letterpress printed cut card panels arranged in a staircase arrangement

Format

Readership

References

- ↑ Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Erik Satie". Encyclopedia Britannica, 5 Apr. 2024, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Erik-Satie. Accessed 11 May 2024.

- ↑ Chen, Julie. Flying Fish Press Website. Flying Fish Press, 2023, Berkeley, CA, https://flyingfishpress.com/. Accessed 11 May 2024.

- ↑ Tetenbaum, Barbara. “Triangular Press ~ Oregon.” Vamp & Tramp, Booksellers, LLC, 13 July 2022, http://www.vampandtramp.com/finepress/t/triangular.html. Accessed 11 May 2024.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Chen, Julie, Erik Satie, and Barbara Tetenbaum. Ode to a Grand Staircase (for Four Hands). Berkeley, Calif.: Flying Fish Press , 2001.

- ↑ Julie Chen. Center for Book Arts, https://centerforbookarts.org/people/julie-chen. Accessed 11 May 2024.

- ↑ “Julie Chen.” National Museum of Women in the Arts, https://nmwa.org/art/artists/julie-chen/. Accessed 11 May 2024.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Flying Fish Press Website. Flying Fish Press, https://flyingfishpress.com/. Accessed 11 May 2024.

- ↑ Barbara Tetenbaum. Reed College, https://www.reed.edu/faculty-profiles/profiles/tetenbaum-barb.html. Accessed 11 May 2024.

- ↑ “Faculty Profiles - Barbara Tetenbaum.” Reed College, https://www.reed.edu/faculty-profiles/profiles/tetenbaum-barb.html. Accessed 11 May 2024.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Doumato, Lamia. Text As Inspiration : Artists' Books and Literature. Washington, D.C.: Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, 2011.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 11.8 Pigza, Jessica. “Book Art Resources: Brief History of Artists’ Books.” Yale Library, https://guides.library.yale.edu/c.php?g=295819&p=1972527. Accessed 11 May 2024.

- ↑ Erik Satie. Hulton Archive/Getty Images. Encyclopaedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Erik-Satie. Accessed 12 May 2024.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Erik Satie". Encyclopedia Britannica, 5 Apr. 2024, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Erik-Satie. Accessed 13 May 2024.

- ↑ Satie, Erik, and Bruno Fontaine. Erik Satie. Paris: Aparte, 2015.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named“book”