Jiu Huang Ben Cao: A Plant Atlas for Famine

Introduction

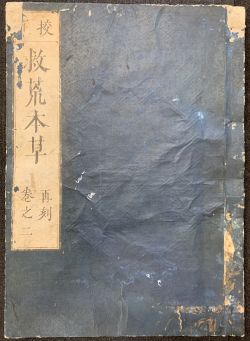

Jiu Huang Ben Cao ("Materia Medica for Famine Relief") was an illustrated botanical manual for plants that could be used for survival during famines, written by Zhu Su in the Ming dynasty. The book has multiple different editions with this particular one likely being the first Japanese edition published around 1716 in Kyoto (京都) by Chōshōdō (長松堂). A total of 414 species of plants were recorded, each with exquisite woodcut illustrations. Among them, 245 types of grass, 80 types of wood, 20 types of grain, 23 types of fruits, and 46 types of vegetable were organized into different sections. The edible parts were further categorized into leaves, roots, fruits, and so on to facilitate identification. The author not only illustrated many of the collected plants, but also described the morphology, growing environment, and processing methods. The book was based on careful observations of collected plants specimens and was considered to be of relatively high academic value by many botanists.

History

Prince Zhu Su was the fifth son of the Hongwu Emperor, who was the founder of the Ming dynasty. He was a talented scholar with a keen interest in medicine. When he was banished to Yunnan in 1389, Zhu witnessed the difficult circumstances people were living in and learned that many of them were suffering from diseases and the lack of medicine. He realized the importance and urgency of compiling prescription books that could be useful for people during famines. Upon returning to Kaifeng, he started organizing a group of scholars, gathering skilled painters, and collecting a large number of books. He also set up a botanical garden to grow various plants that were known from surveys to be edible to conduct observation experiments. Although he was banished to Yunnan once once in 1399, he never stopped his research on prescriptions and plants that could be used in a famine. In 1406, the book Jiu Huang Ben Cao was published.

The original edition contained two volumes. New editions started to emerge in the sixteenth century. The second edition was ordered by Bi Mengzhai, the governor of Shanxi, in 1525. The third edition was printed in 4 volumes in 1555 with woodblocks engraved by Lu Dong. Unfortunately, it mistakenly identified Zhu Su's son, Zhou Xianwang (周憲王), as the author. This error later appeared again in works such as Li Shizhen's Bencao gangmu (本草綱目) and Xu Guangqi's Nongzheng quanshu (農政全書). A few more editions were printed in 1562 by Hu Cheng and in 1586 by Zhu Kun. In 1639, it was reprinted with 413 plants as part of the Xu Guangqi's Nongzheng quanshu (農政全書) published by Hu Wenhuan (胡文焕). Jiu Huang Ben Cao was first published in Japan in 1716, with various manuscript copies also produced. According to Weito Okanishi, a Japanese researcher on Chinese herbalism, the Jiu Huang Ben Cao was highly regarded in Japan during the Tokugawa period (1603-1867) with fifteen research papers on it. The book was translated into English by the English pharmacologist Iborn, who also performed compositional analysis and claimed that the original woodcut of the Jiu Huang Ben Cao was superior to that of the Bencao gangmu. The American botanist , in his book A Short History of Botany, also praised the accuracy of the illustrations and remarked that it surpassed those of the Europe at the time.

Woodblock Printing

Fukurotoji Binding

Innovations

In addition to the edible plants, the book also included some poisonous plants that could be eaten after certain processing when food was rare. It is noteworthy that the book proposed to remove the toxicity of poisonous celandine by cooking it with "clean dirt", a method that is theoretically consistent with the chromatographic adsorption and separation invented by the Russian botanist Tsvet in 1906.

Cultural Implications

This book, along with many others such as the Shenzhenfang (神珍方) and the Puji fang (普濟方), have contributed a lot to the development of traditional Chinese medicine.

Jiu Huang Ben Cao from University of Pennsylvania's Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts [1]

References

- ↑ 顾媛媛. "《十竹斋笺谱》木版水印技艺传承与文化拓展." 艺术百家, no. 5 (2014): 251–252.