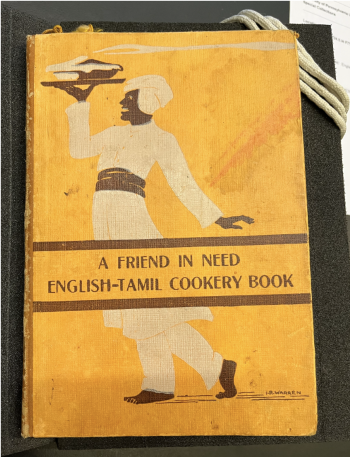

A Friend in Need: English-Tamil Cookery Book

A Friend in Need: English-Tamil Cookery Book is a fundraising cookbook created by the Women’s Workshop of the Friend In Need Society (F.I.N.S.). The book was created and printed in Madras, India, which is currently known as Chennai, India. This copy is currently held at the Kislak Center for Special Collections at the University of Pennsylvania. Printed in 1937 by the Diocesan Press in Vepery, the book contains recipes written in English and Tamil side-by-side, serving as a reference for Tamil-speaking cooks to prepare Western dishes for their British employers. To the contemporary reader, beyond providing recipes, A Friend in Need: English-Tamil Cookery Book presents a view into domestic life in India during British rule and the relationship between the British and natives.

Background

Madras, India

Until 1600, Madras was named Madraspatnam and was a small rural village on the Coromandel Coast.[1] From the early 1600s, the British started to venture into India for spice trade and eventually exerted government control until 1947 when India won independence.[2] Madras was first overtaken by British control in 1636 and it became the location of Britain’s first fortification in India (Fort St. George in 1644, built by the East India Company).[3] Madras became the administrative and military hub of the British East India Company in south India, developing an extensive railway network to promote British-controlled trade. Madras was renamed Chennai in 1996.

A Friend in Need: English-Tamil Cookery Book was published in 1937, during which India was under the control of the British Raj.[4] During this period of direct rule, control of the Indian government was through British viceroys, and British people were in India as part of the military and government. As a result, an increased number of British people moved to India, often with families. They may have established communities such as the Friends In Need Society (F.I.N.S.) to build social and philanthropic networks.

Friend In Need Society (F.I.N.S.)

The Friend In Need Society (F.I.N.S) was the creator of this cookbook. Limited information on this society exists other than the brief description included in the book, one digitized copy of a report released by the society in 1882, and transcripts from 1947 interviews with residents of the F.I.N.S. home.

From the cookbook, F.I.N.S. was founded in 1813 to “assist the deserving poor and to provide a Home for aged, infirm and destitute European and Anglo-Indian Christian of every denomination.” The introduction states that all profits from the sale of the book will go towards the society. The society was headquartered on Poonamallee Road in Madras.

The 1882 report, digitized by the University of London Senate House Library, stated that the society had 57 members. The leadership listed in the report were all men, but there was a Women’s Workshop (who were the creators of this cookbook). The purpose of the Workshop is unclear, but it was possibly a community for the wives of the men who were part of the society. The society appeared to have a close relationship with an unnamed local church led by Bishop Colgan, who approved a “Friend-in-Need Sunday,” during which collections were held for the society. The main purpose of the society appears to be fundraising, which went to support poor Europeans and Anglo-Indians in Madras. The term “Anglo-Indians” meant people with both European and Indian ancestry.[5] The report explicitly states that the society did not benefit the native poor. The society served its target population by both providing pensions and housing to those in need. In 1882, the society provided 245 permanent and 104 temporary pensions (Rs. 2 to Rs. 5 per month) and housed 87 people.

The University of Cambridge Centre of South Asian Studies has an archive of interviews with eight residents of the F.I.N.S. home from 1974. The ethnic backgrounds of the interviewees were European (French and Portuguese) or Anglo-Indian. The residents were previously railway employees or in the army.

Today, F.I.N.S. may exist as an old-age home in Chennai, but it is difficult to say with certainty that the listed organization is the same as the F.I.N.S. who published the cookbook, as the address has changed and the founding date is different.

Printing in India and Madras

Research on printing in India was obtained using Glimpses of Early Printing and Publishing in India by P. A. Mohanrajan, a book on the history of printing in India housed at Van Pelt-Dietrich Library.[6]

A Friend in Need: English-Tamil Cookery Book was printed by the Diocesan Press in Vepery, the oldest printing press in India. Christian missionaries made printing in India widespread in the 1700s, but printing technology was introduced as early as 1577. The technological development of the printing press occurred outside of India and was brought to India by missionaries. Printing in India originated as a means to spread the Christian Gospel to Indians through local languages. As such, most of the printing presses were affiliated with local missions or churches. Additionally, missionaries relied on printed texts explaining the lives and religion of natives. Tamil was the first language in India to be printed.

The first printing press in Madras was introduced in 1757 by Johann Phillip Fabricus, a German Christian missionary. He established the S.P.C.K. Press in Vepery, later renamed to the Diocesan Press. The first works printed at this press were a Hymn Book and Tamil-English dictionary, and movable type was used to print the texts.

Tamil typography was first developed by the Portuguese in 1679 using wooden engraved blocks. Soon after, however, they created a wooden movable type. Modern Tamil typography was developed by Phineas Rice Hunt, a printer from the American Mission Press in 1850. Dissatisfied with existing Tamil typefaces, Hunt designed a new face using metal that gave characters a more regular size, improved alignment, and even spacing. The development of the typeface was completed in 1862. Given the timeline of developments, A Friend in Need: English-Tamil Cookery Book was likely printed using metal moveable type.

Community Cookbooks

A Friend in Need: English-Tamil Cookery Book may be an example of a community cookbook, which was a fundraising strategy originating in the United States during the Civil War.[7] Originally created by Northern women who wanted to raise money to support the Sanitary Commission of the Civil War, churches and other charity organizations later adopted the sale of community cookbooks to raise money for their own causes. Most community cookbooks were locally printed and not copyrighted.[8] Almost all included advertisements at the end of the book to cover printing costs. These cookbooks were almost always produced by women and served as an important avenue for personal development, friendship, and opportunities for public life. The “community” aspect of these cookbooks was emphasized because the recipes were compiled by members of the charitable group and not through professional chefs.

What sets this cookbook apart from most community cookbooks is the professional nature of the book's printing and binding. Most community cookbooks were hand-bound with plastic coil, yet A Friend in Need: English-Tamil Cookery Book appears to be bound at a printing press (see Construction and Material Properties. However, many of the distinguishing features of community cookbooks still apply to this book, such as the sale for fundraising, collaboration among women for creation and publication, and inclusion of advertisements.

Physical Analysis

Metadata

The book was printed in 1937 (unknown month), although the introduction is dated August 1937. The book was sold by the Secretary of the F.I.N.S. Women’s Workshop, but there is no copyright noted. The book was sold for Rs. 2-8, likely on a sliding scale due to the fundraising purpose of the cookbook. There is no listed author, which is common for community cookbooks, but the introduction was written by Ella Nuttall, who is listed as the Chairman of F.I.N.S. Women’s Workshop. The translator of the book is unacknowledged. The illustrations on the front cover of the book and in the introduction are attributed to “I.R. Warren," who has no other searchable works today.

The introduction states that the included recipes are old favorites of members of the Committee and friends, a feature of community cookbooks. Several recipes were also taken from previously published sources, and the Highclerc Cookery Book was cited as one of the sources. There are also recipes from private collections in unacknowledged published sources, but the committee does not list their names and “hopes oversight will be pardoned.”

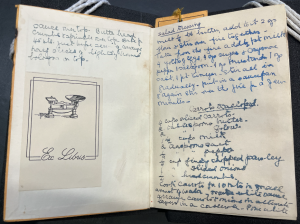

The previous owner(s) of the book is unknown. There is a blank bookplate on the pastedown, titled “Ex Libris.” It seems that only one person annotated the book, if there were multiple owners, as all of the marginalia is the same handwriting. The owner may have purchased and used this book in Madras, given the publication location of the added newspaper clippings (see Marginalia/Clippings). The date when the University of Pennsylvania obtained the book, and the source of the acquisition, are unknown.

Construction and Material Properties

The book is rectangular and in the codex format. The book construction was contemporary with the publication date. The book was bound with a hard cardboard cover, indicating the intentional durability of the construction. The binding appears to be attached to the book using a mesh, and the binding is separating from the flyleaf due to use. On the spine itself, there is a hole with a metal ring reinforcement to allow for a built-in bookmark. The string and bookmark are still intact and functional. The bookmark is attached to a string via a knot, and the string is attached to the spine also with a knot. The bookmark features a brief description of the F.I.N.S.

The book is printed entirely in black ink, other than pages 52-53, which feature a full-color advertisement of SandW Fine Foods (see Ads). The paper in the full-color pages is glossy, which is different from the matte paper in the other sections of the book. Within the book, there are several burn marks spanning pages 1-11 and pages 68-72, potentially demonstrating that this book was actually used in the kitchen while cooking.

For the recipes, English and Tamil are written side-by-side, allowing for seamless communication between the English-speaking “mistress” and Tamil-speaking cook. The book only contains British/Western recipes.

The book has a table of contents with page numbers, which demonstrates that the book is meant for discontinuous reading. However, the table of contents is not translated into Tamil like how the rest of the book is, only allowing the English speaker to find the recipes this way. Possibly, this book was created so the British person who owned the book could look through it to find a recipe, and then show their cook the translation (i.e., the cook may not have been finding recipes on their own).

Each recipe is numbered within each section (numbering restarts with a new section, starting at 1), allowing for quick navigation. There are subsections within each section (for example, “general stock for soup” is 1., but there’s a and b for meat stock vs. vegetable stock)

Intended Audience

This copy was likely used by an English-speaking person living in Madras, given the scattering of English newspaper clippings throughout the book (see Marginalia/Clippings). Based on the introduction of the book, the intended audience was an English-speaking person living in India.

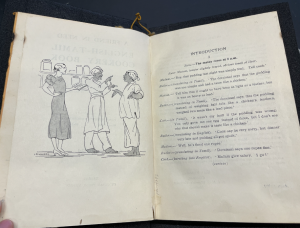

The introduction is written by Ella Nuttall, who is the Chairman of the F.I.N.S. Women’s Workshop in Madras. This is the only section of the book with a directly attributed author; the other recipes are attributed to the committee as a whole. The introduction clearly defines the intended audience and purpose of the book. Recipes from the book are to be selected by the Anglo-Indian mistress in English and given to the Tamil-speaking cook to execute. Additionally, the introduction was not translated into Tamil, which also demonstrates how the book was likely intended to be purchased by a European or Anglo-Indian for the execution of recipes by their Tamil-speaking cook. The introduction also discusses how the book was written in English first, then translated into Tamil. Like most community cookbooks, this book was likely distributed through personal networks of the Women’s Workshop, such as other society members, friends, and family.

Content

Sections

The sections of the books include hors d'oeuvres, soups, fish, entrees, meats, sauces, salads, savouries, puddings (hot and cold), ices, cakes (large and small), scones, sweets, and household hints.

At the start of each section (except for hors d'oeuvres, entrees, sauces, salads, savouries, puddings, ices, cakes), there’s a preface/short explanation of basics of that technique/food group that is also translated into Tamil. This might indicate how the creators of the book assumed that the Indian cooks were not accustomed to Western-style cooking and would need more background information to properly prepare dishes.

The recipe book then lists the recipes. For each food, there is a list of ingredients with measurements and cooking instructions included. There are multiple recipes per page. At the end of the book, after all of the recipes, there are 31 household “hints” and weight/measurement conversions, covering topics such as what to do if mayonnaise curdles.

Marginalia/Clippings

There are extensive notes throughout the book, mostly of additional recipes, likely written by the owner (or one of the owners) of the book. There are annotations on the back of the cover and also flyleaf, as well as throughout the book. At the end of each section, there are two pages for notes, which encourages annotations in the book and using it as a reference or depository for personal recipes. The handwriting is consistent throughout the book, indicating that likely only one person wrote in the book. Some of the ink seems to be bleeding. The annotations/notes are written in different colors, so they were possibly written at different times (i.e., the reader came back to the book at different points to add more recipes). Additionally, because there is space for the readers to add notes after each chapter, the book was likely used as a place to store additional recipes that people encountered. The book was probably read multiple times and used frequently while cooking.

There are also four newspaper clippings written in English located throughout the book.

Ads

At the very end of the book (after the recipes/household tips) is 10 pages of advertisements. There is more info about F.I.N.S. on the first page. All of these ads seem to be for British people living in Madras, which further supports that the intended audience of the book likely were English-speaking people living in Madras, as the advertisements at the end of the book all relate to British/European goods/services that are available in India. Additionally, these advertisements are not translated into Tamil.

Historical Significance

A Friend in Need: English-Tamil Cookery Book provides a poignant view into the relationship the British had with native Indians during the British Raj. Not only does the text of the introduction highlight that the purpose of the book is to put the English-speaking “mistress” in direct communication with the Tamil-speaking cook, but the illustration highlights the dynamic between the two groups. The English-speaking mistress is in a position of power over the native cook by directing his actions, reprimanding him, and fining him. This illustration was created by

Furthermore, the book holds the history of community cookbooks. Beyond a fundraising tactic, community cookbooks are seen as a part of the feminist movement. Although the writers of the books were typically a division of a larger organization (as the Women’s Workshop was of F.I.N.S.), scholars have conceptualized the community cookbook as a way that women reclaimed their subservient roles.[8] Through the collection, production, and distribution of community cookbooks, women were able to reshape their domestic identities by collectively organizing as women, sharing knowledge, and creating an economic sphere.

References

- ↑ Barlow, Glyn. “The Story of Madras.” Project Gutenberg, 1921, https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/26621/pg26621-images.html.utf8.

- ↑ India - The British, 1600–1740. https://www.britannica.com/place/India/The-British-1600-1740. Accessed 25 Apr. 2023.

- ↑ “A Postcard from Madras: A City Born of the Colonial Encounter.” Origins, https://origins.osu.edu/connecting-history/postcard-madras-city-born-colonial-encounter?language_content_entity=en. Accessed 25 Apr. 2023.

- ↑ British Raj | Imperialism, Impact, History, & Facts. 31 Mar. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/event/British-raj.

- ↑ Anglo-Indian | People |. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Anglo-Indian. Accessed 25 Apr. 2023.

- ↑ Mohanrajan, P. A. Glimpses of Early Printing and Publishing in India: Their Contribution Towards Democratisation of Knowledge. Madras: Mohanavalli Publications, 1990. Print.

- ↑ Bower, Anne L. "Our Sisters' Recipes: Exploring "Community" in a Community Cookbook." Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 31, no. 3, 1997, pp. 137-151.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Ferguson, Kennan. “Intensifying Taste, Intensifying Identity: Collectivity through Community Cookbooks.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, vol. 37, no. 3, Mar. 2012, pp. 695–717.