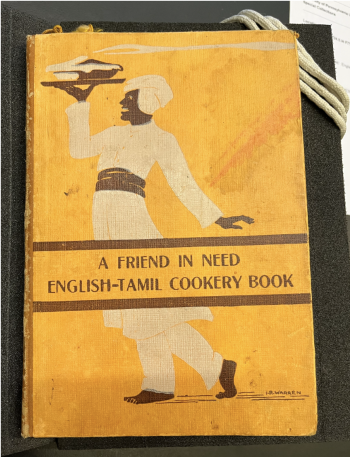

A Friend in Need: English-Tamil Cookery Book

A Friend in Need: English-Tamil Cookery Book is a fundraising community cookbook created by the Women’s Workshop of the Friend In Need Society (F.I.N.S.). The book was created and printed in Madras, India, which is currently known as Chennai, India. This copy is currently held at the Kislak Center for Special Collections at the University of Pennsylvania. Printed in 1937 by the Diocesan Press in Vepery, the book contains recipes written in English and Tamil side-by-side, serving as a reference for Tamil-speaking cooks to prepare Western dishes for their British employers. To the contemporary reader, beyond providing recipes, A Friend in Need: English-Tamil Cookery Book presents a view into domestic life in India during British rule and the relationship between the British and natives.

Background

Madras, India

Until 1600, Madras was named Madraspatnam and was a small rural village on the Coromandel Coast.[1] From the early 1600s, England started to venture into India for spice trade and eventually exerted government control until 1947 when India won independence.[2] Madras was first overtaken by British control in 1636 and it became the location of Britain’s first fortification in India (Fort St. George in 1644, built by the East India Company).[3] Madras became the administrative and military hub of the British East India Company in south India, developing an extensive railway network to promote British-controlled trade. Madras was renamed Chennai in 1996.

A Friend in Need: English-Tamil Cookery Book was published in 1937, during which India was under the control of the British Raj.[4] During this period of direct rule, control of the Indian government was through British viceroys, and British people were in India as part of the military and government. As a result, an increased number of British people moved to India, often with families. They established communities such as the Friends In Need Society (F.I.N.S.) to provide social and philanthropic networks.

Friend In Need Society (F.I.N.S.)

The Friend In Need Society (F.I.N.S) was the creator of this cookbook. Limited information on this society exists other than the brief description included in the book, one digitized copy of a report released by the society in 1882, and transcripts from 1947 interviews with residents of the F.I.N.S. home.

From the cookbook, F.I.N.S. was founded in 1813 to “assist the deserving poor and to provide a Home for aged, infirm and destitute European and Anglo-Indian Christian of every denomination.” The introduction states that all profits from the sale of the book will go towards the society. The society was headquartered on Poonamallee Road in Madras.

The 1882 report, digitized by the University of London Senate House Library, stated that the society had 57 members. The leadership listed in the report were all men, but there was a Women’s Workshop (who were the creators of this cookbook). The purpose of the Workshop is unclear, but it was possibly a community for the wives of the men who were part of the society. The society appeared to have a close relationship with an unnamed local church led by Bishop Colgan, who approved a “Friend-in-Need Sunday,” during which collections were held for the society. The main purpose of the society appears to be fundraising, which went to support poor Europeans and Anglo-Indians in Madras. The term “Anglo-Indians” meant children with both European and Indian ancestry.[5] The report explicitly states that the society did not serve the native poor. The society served its target population by both providing pensions and housing to those in need. In 1882, the society provided 245 permanent and 104 temporary pensions (Rs. 2 to Rs. 5 per month) and housed 87 people.

The University of Cambridge Centre of South Asian Studies has an archive of interviews with eight residents of the F.I.N.S. home from 1974. The ethnic backgrounds of the interviewees were European (French and Portuguese) or Anglo-Indian. The residents were previously railway employees or in the army. Today, F.I.N.S. may exist as an old-age home in Chennai, but it is difficult to say with certainty that the listed organization is the same as the F.I.N.S. who published the cookbook, as the address has changed and the founding date is different.

Printing in India and Madras

Research on printing in India was obtained using Glimpses of Early Printing and Publishing in India by P. A. Mohanrajan, a book on the history of printing in India housed at Van Pelt-Dietrich Library.[6]

A Friend in Need: English-Tamil Cookery Book was printed by the Diocesan Press in Vepery, the oldest printing press in India. Christian missionaries made printing in India widespread in the 1700s, but printing technology was introduced as early as 1577. The technological development of the printing press occurred outside of India and was brought to India by missionaries. Printing in India originated as a means to spread the Christian Gospel to Indians through local languages. As such, most of the printing presses were affiliated with local missions or churches. Additionally, missionaries relied on printed texts explaining the lives and religion of natives. Tamil was the first language in India to be printed.

The first printing press in Madras was introduced in 1757 by Johann Phillip Fabricus, a German Christian missionary. He established the S.P.C.K. Press in Vepery, later renamed to the Diocesan Press. The first works printed at this press were a Hymn Book and Tamil-English dictionary, and movable type was used to print the texts.

Tamil typography was first developed by the Portuguese in 1679 using wooden engraved blocks. Soon after, however, they created a wooden movable type. Modern Tamil typography was developed by Phineas Rice Hunt, a printer from the American Mission Press in 1850. Dissatisfied with existing Tamil typefaces, Hunt designed a new face using metal that gave characters a more regular size, improved alignment, and even spacing. The development of the typeface was completed in 1862. Given the timeline of developments, A Friend in Need: English-Tamil Cookery Book was likely printed using metal moveable type.

Community Cookbooks

A Friend in Need: English-Tamil Cookery Book is an example of a community cookbook, which was a fundraising strategy originating in the United States during the Civil War.[7] Originally created by Northern women who wanted to raise money to support the Sanitary Commission of the Civil War, churches and other charity organizations later adopted the sale of community cookbooks to raise money for their own causes. Most community cookbooks were locally printed and not copyrighted.[8] Almost all included advertisements at the end of the book to cover the costs of printing. These cookbooks were almost always produced by women and served as an important avenue for personal development, friendship, and opportunities for public life. The “community” aspect of these cookbooks was emphasized by the fact that the recipes were compiled by members of the charitable group and not through professional chefs.

Physical Analysis

Metadata

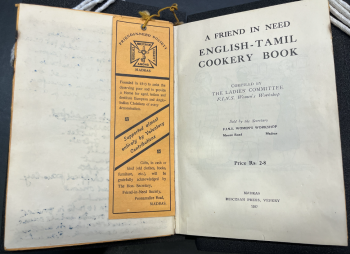

The book was printed in 1937 (unknown month), although the introduction is dated August 1937. The book was sold by the Secretary of the F.I.N.S. Women’s Workshop, but there is no copyright noted. There is no listed author, which is common for community cookbooks, but the introduction was written by Ella Nuttall, who is listed as the Chairman of F.I.N.S. Women’s Workshop. The translator of the book is unacknowledged. The illustration on the front cover of the book is attributed to “I.R. Warren.”

The introduction states that the included recipes are old favorites of members of the Committee and friends, a feature of community cookbooks. Several recipes were also taken from previously published sources, and the Highclerc Cookery Book was cited as one of the sources. There are also recipes from private collections in unacknowledged published sources, but the committee does not list their names and “hopes oversight will be pardoned.”

The previous owner(s) of the book is unknown. There is a blank bookplate on the pastedown, titled “Ex Libris.” It seems that only one person annotated the book, if there were multiple owners, as all of the marginalia is the same handwriting. The owner may have purchased and used this book in Madras, given the publication location of the added newspaper clippings (see Marginalia/Clippings). The date when the University of Pennsylvania obtained the book, and the source of the acquisition, are unknown.

Construction and Material Properties

The book is in the codex format and is rectangular. The book construction was contemporary with the publication date. The book was bound with a hard cardboard cover, indicating the intentional durability of the construction. The binding appears to be attached to the book using a mesh, and the binding is separating from the flyleaf due to use. On the spine itself, there is a hole with a metal ring reinforcement to allow for a built-in bookmark. The string and bookmark are still intact and functional. The bookmark is attached to a string via a knot, and the string is attached to the spine also with a knot. The bookmark features a brief description of the F.I.N.S.

The book is printed entirely in black ink, other than pages 52-53, which feature a full-color advertisement of SandW Fine Foods (see Advertisements). The paper in the full-color pages is glossy, which is different from the matte paper in the other sections of the book. Within the book, there are several burn marks spanning pages 1-11 and pages 68-72, potentially demonstrating that this book was actually used in the kitchen while cooking.

Intended Audience

Content

Sections

Marginalia/Clippings

test

Historical Significance

References

- ↑ Barlow, Glyn. “The Story of Madras.” Project Gutenberg, 1921, https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/26621/pg26621-images.html.utf8.

- ↑ India - The British, 1600–1740. https://www.britannica.com/place/India/The-British-1600-1740. Accessed 25 Apr. 2023.

- ↑ “A Postcard from Madras: A City Born of the Colonial Encounter.” Origins, https://origins.osu.edu/connecting-history/postcard-madras-city-born-colonial-encounter?language_content_entity=en. Accessed 25 Apr. 2023.

- ↑ British Raj | Imperialism, Impact, History, & Facts. 31 Mar. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/event/British-raj.

- ↑ Anglo-Indian | People |. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Anglo-Indian. Accessed 25 Apr. 2023.

- ↑ Mohanrajan, P. A. Glimpses of Early Printing and Publishing in India: Their Contribution Towards Democratisation of Knowledge. Madras: Mohanavalli Publications, 1990. Print.

- ↑ Bower, Anne L. "Our Sisters' Recipes: Exploring "Community" in a Community Cookbook." Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 31, no. 3, 1997, pp. 137-151.

- ↑ Ferguson, Kennan. “Intensifying Taste, Intensifying Identity: Collectivity through Community Cookbooks.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, vol. 37, no. 3, Mar. 2012, pp. 695–717.