A Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practicall Musicke

Overview

A Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practicall Musicke[1] is a collection of popular music theory concepts of the 16th century for educational use. It was written and compiled in 1597 by Thomas Morley, a compatriot of Shakespeare and 16th century English composer from the short-lived but intense Madrigal School of music.

Later Reprints

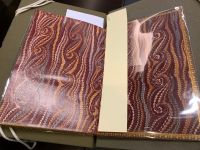

The copy housed in the University of Pennsylvania's Van Pelt rare book collection, however, was printed in 1608 by Humfrey Lownes. Lownes was a relatively prodigious printer, working often with his brother Matthew (a bookseller/distributor). He printed predominantly religious texts with 234 of the 386 items he issued being theological, before later moving into literature and music.[2] Van Pelt’s copy of the book, however, does not seem to be in its original binding, rather it seems to have been rebound in the 1800s (the inside cover designs and outer binding being consistent with designs of the time).

Physical Attributes

The book was printed in the form of a folio, and is comprised of a combination of diagrams, sheet music, and writing (mostly in the form of a dialogue that echoes a teacher/student relationship to aid the book’s educational purpose). The book was printed through a combination of woodblocks (predominantly for the title page and the insignias at the beginning of chorales), and movable type (for the written portions and sheet music). The majority of the book is formatted as the dialogue with sheet music, all of which is written in mensural notation, interspersed throughout in order to provide examples of what is being discussed. The book ends, however, with a compilation of several multi-voiced chorales in a section at the end. These chorales are often four to six part harmonies formatted with different groups of voices being oriented in different directions on the page, to maximize the number of people that could stand around the book and read its music. [3]

Printing Techniques

Although the technique for printing music is extremely close to the technique for printing words in its steps, it requires an entirely different set of characters, therefore only specialized printing shops could print music, as it required 400-500 characters beyond what the average printer would have. [4] To print the sheet music, each note would be in a sense one unit—the head, stem, and five staff lines all being the same piece of type—and the printer would design the page by placing note by note next to each other (from left to right in reverse of course). There was a unique character for each note in terms of both pitch and time value. For symbols such as rests, clefs, and accidentals, the printer would have to create the staff from scratch, consisting of four staff lines resembling dashes and the symbol somewhere in their midst. [3] In addition to just printing the right notes, special attention had to be paid to the spacing of the music to make sure it is readable during a performance (any musician knows that reading a sheet of squeezed together notes with no bar markings or demarcations is near impossible), so to aid this there were pieces that were just blank staff lines and measure markers to space out the music. [3]

Because of the increased cost in needing to have so many specialized characters, corners were cut where they could be in order to save some money. The observant viewer will notice one such shortcut which is that the stems were drawn connecting to the middle of the notes’ heads rather than their sides as was convention. Before printing, all notes (regardless of if they were up-stem or down-stem) were drawn with the stem on the same side (Bernstein), however, in order to do this in print would have required double the characters, and by drawing the stems in the middle, the characters could be flipped upside down in order to be either the note’s down-stem or up-stem version.

Impact on Modern Convention

This is a case of technology altering content by its limitations—eventually later in the 1600s, the stems moved back to the sides of the notes, however, to maintain the economical advantage of the notes being reusable, the stem is just on opposite sides of the head depending on whether it is up-stemmed or down-stemmed (up-stem notes have the stem on the left side, down-stem on the right). This has now become standard convention not only in printed music, but also in handwritten music. [4]

Historical Significance

A Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practicall Musicke is most noted in other literature as being the first widespread collection of music theory concepts and examples, in a sense what we might consider the first music theory textbook. [5] Anyone who has taken a music theory class will recognize the format almost exactly: a book full of detailed writing explaining music theory concepts, sheet music to show those concepts in action, and even diagrams that we might consider “cheat sheets” to summarize the teachings at the end of a chapter.

Another notable aspect to this book in its historical context is the fact that musical moving-type printing did not last very long. As can be seen in the sheet music printed here, it is definitely not the ideal form of music printing—the staff lines are not straight or fluid, they are readable but unaligned. This type of printing also worked for multi-part vocal harmonies, but once music started to be composed more so for the piano or orchestras, oftentimes with many more notes, one on top of the other, and in more rapid succession, this method became untenable. In the mid 1600s music engraving became ubiquitous. This method wherein metal plates would be hand-engraved with the more complex sheet music then used to print whole pages obviated the need for movable music type, so not only is this book significant for its early-music textbook qualities, but also because it is a remnant of a very specific time and music culture.[4]

Implications for Modern Times

When viewed alongside current music theory textbooks, a lot can be revealed about the subject as a whole. In recent times, music theory education has become more and more critiqued due to its perceived racist tendencies. For what Western schools and institutions claim to be comprehensive music theory, is only the theory of dead, European, (usually) white, (usually) male composers from the 17th and 18th centuries. Not only is this theory in many ways irrelevant to music made today, but this viewpoint completely erases other types of music i.e South Asian music or African music, which have entirely different, but equally valid theories behind them. By not incorporating these alternate theories into the Western view of music theory, we are severely limiting our understanding of the field.

This book backs up this concept, because there is an almost entire overlap between what is written in it and what is taught in the first four music theory classes one takes at any Western university today. This is not to say it is necessarily a bad thing to teach these concepts, but music has changed significantly in the past 400 years and to not update the curriculum is a disservice. The fact that there is so much overlap is like if one went to college to study astrophysics and the first 4 classes they took only taught up to Copernicus. Sure, there is some relevant information and basis of understanding to be found from back then, but we’ve moved a long way past. Morley writes about concepts such as not using the three chord of a scale, or the need to avoid parallel fifths, both of which are still taught today, and yet both of which are staples of modern pop and rock music. This book and its overlap to modern music theory teaching creates a very eye-opening view into the flaws of modern theory education.

References

- ↑ Morley, Thomas. A Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practicall Musicke. Humfrey Lownes, 1608.

- ↑ Brink, Jean R. Publishing Spenser's View of the Present State of Ireland: From Matthew Lownes and Thomas Man (1598) to James Ware (1633). Spenser Studies 29 (2014): 295-311. ProQuest. Web.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Bernstein, Jane A. Music Printing In Renaissance Venice : the Scotto Press, 1539-1572. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Kelly, Thomas Forrest. Capturing Music : the Story of Notation. First edition.

- ↑ Mann, Joseph Arthur. “‘Both Schollers and Practicioners’: The Pedagogy of Ethical Scholarship and Music in Thomas Morley’s ‘Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practicall Musicke.’” Musica Disciplina, vol. 59, 2014, pp. 53–92, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24893218.