World War I Trench Newspapers

Trench newspapers are publications produced, published, and circulated by soldiers on the Western and Eastern fronts during the First World War. In the standoffs that persisted from 1914 to 1918 on the Western and Eastern fronts, trench warfare transformed the reality of warfare in Europe. In the wake of the tragedy and suffering that trench warfare created, Trench Newspapers arose as a source of news, entertainment, and distraction for soldiers in the British, French, German, and Canadian militaries, with limited publications among other national militaries. Trench newspapers were most often produced as satirical journals, by hand, on a limited basis by officers at war. They took advantage of a wide array of hand publishing techniques and provide insight into the attitudes and emotions of soldiers on the front lines of the First World War. A large collection of French trench newspapers are currently housed at the University of Pennsylvania's Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts.

Production, Circulation, and Provenance

Trench newspapers, including those produced by the British and French militaries, were most often drafted and produced by “middle-class, low ranking officer[s]” with backgrounds that would lend themselves to writing and publishing. They frequently consisted of older men with teaching or printing backgrounds, with many working as lawyers, artists, teachers, and journalists [1] before being conscripted into their respective militaries. While a significant portion of newspapers were produced by soldiers in the lower ranks, the majority were produced and circulated by officers and junior officers [1]. Most trench newspapers were produced behind fixed front lines, most often in lulls in combat, separated from enemy lines. In the case of French newspapers, most newspapers were printed in Paris before being distributed among the ranks of soldiers, but few used large-scale printing technologies on account of their relatively short-runs and limited financial backing. Most Trench newspapers were purchased by soldiers before being printed as a part of a pseudo “subscription service” [1], mostly to cover the costs of production. Once produced, most trench newspapers were distributed via military post [1]. To accommodate their short print runs, newspapers were rarely printed en masse: most copies were printed on an extremely limited basis, and then passed from hand to hand among soldiers [1]. In many cases, Trench Newspapers would have been tacked onto bulletin boards or in plain view for soldiers to see [1].

Provenance

The Trench newspapers collected and maintained as a part of their World War I Print and Media collection are mostly French newspapers, likely collected and donated by a single party. Of the newspapers examined, a few samples showed penciled price tags in the upper-righthand corner, indicating that some Trench newspapers were sold and collected after the conclusion of the First World War.

Reproduction Techniques

Based on an analysis of entries into the World War One print and media collection at the Kislak Center at the University of Pennsylvania, most printed trench newspapers were published sporadically and on a limited basis, in many cases with only one edition. When they were printed, however, it was often with cheap, accessible techniques such as mimeography or hectography. In rare instances, trench newspapers were printed professionally.

Substrates

Substrates used in printing varied based upon the army and printing technique used. Professionally-printed trench newspapers likely used high-acid, machined paper, much like the paper used in civilian newspapers in the early 20th century.

Mimeography

Mimeography stands out as one of the most cost-effective, accessible, and widespread copying and publication methods of the early 20th century. Originally patented by Thomas Jefferson and produced as the “Gestetner” machine in Europe by the AB Dick Company [2] , mimeography reliably produced copies of a masterwork via stencil. The low cost and simplicity of mimeography made it an ideal technique for soldiers of the First World War. The mimeographs used to produce trench newspapers during the First World War created stencils by using a stylus or typewriter to remove the wax from a wax-covered sheet, after which ink could be “forced” through a rotary or flat press onto a clean paper sheet [2] .

Hectography

In addition to mimeographic techniques, hectography was frequently employed to produce trench newspapers and journals. In its simplest form, hectography of the 20th century employs gelatin and ink to reproduce copies of a master copy. A metal tray is filled with gelatin paste to create a flat sheet, after which the master copy is carbon-copied and pressed into the gelatin. Clean sheets of paper were then lain onto the gelatin and pressed, transferring the ink from the gelatin onto the sheet. (Van Dijck) Trench newspaper publishers frequently employed hectography because it was cost-effective and, unlike mimeography, required very little investment into specialty materials and equipment. Nevertheless, hectography used for trench newspapers was a laborious process that yielded comparatively fewer copies of the master copy (Van Dijck, Yunus). Hectographically-reproduced materials frequently employed purple ink, which makes trench newspapers in purple ink easily identifiable (Van Dijck) (see La Premiere Ligne).

Lithography

Trench newspapers were rarely produced using lithography, but for those newspapers printed professionally in Paris [1], it’s highly plausible that trench newspapers were produced using lithographic techniques. Early on in the material analysis of the French trench newspapers discussed in this article, it was speculated that lithography was used to produce copies of a master newspaper. Although none of the three samples examined from the Kislak Center were definitely produced using lithography, the lithographic technique used by 20th-century publishers was simple and accessible to many publishers. A design would be drawn onto a smooth surface (such as a stone plate) using a hydrophobic solvent. Ink would then be applied to the surface, attracted to the solvent. The remaining ink was then wiped away, leaving the inked design ready to be transferred onto a clean sheet by pressing it onto the stone (Rhodes). According to Hornstein, early on in the 19th century, lithography in France quickly became associated with the war effort and the representation of military subjects to the public. Hornstein describes lithography as a “social medium” that was popularized outside of academic contexts, making it an ideal process for popular, inexpensive publications. In terms of French newspapers, lithography was key to the historical context in which trench newspapers were produced, shaping the type and layout of material that would be included in newspapers.

Material Analysis of French Trench Newspapers

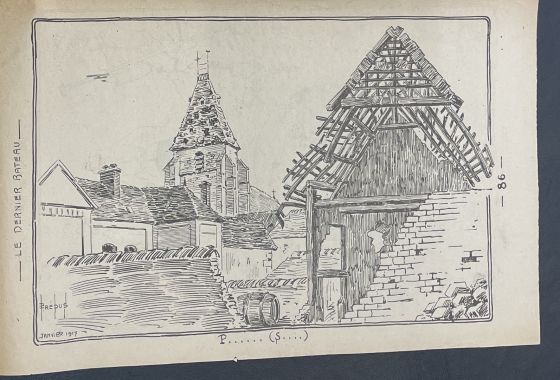

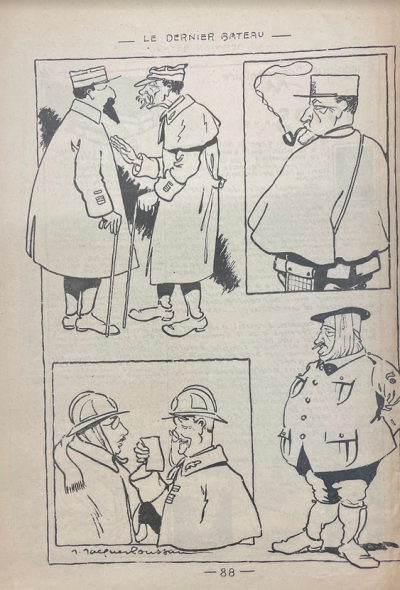

Le Dernier Bateau

Le Dernier Bateau stands out as one of the higher-quality trench newspapers collected by the Kislak Center at the University of Pennsylvania. The newspaper appears to have used much more refined techniques to produce a periodical print newspaper at scale: more than 11 separate editions have been preserved, with editions published from 1915 to 1917 monthly or bi-monthly. The greater investment in this trench newspaper is reflected in the quality: with clear, black, high-quality handwritten text and illustrations on each page of the single-sheet folio. While this newspaper could have been theoretically produced using a mimeograph of a hectograph, it is more likely that this newspaper was printed professionally at a large scale, using lithographic or similar techniques. The lack of marginalia in the newspaper, the crisp, black ink lines, and the length and content of the newspaper give credence to Le Dernier Bateau being printed on a more professional level in Paris. Concerning the substrate itself, this newspaper was printed on think high-acid, machined paper, similar to newspapers being produced in Paris at the time. The newspaper is printed onto a single, uncut sheet and folded twice to create an 8-page, quarto-style print about the size of a sheet of modern printer paper. Each page is labelled with a page number starting with 81, confirming that this edition is part of a greater series. The paper itself has worn significantly over the past century: the creases were extremely fragile and difficult to handle without tearing, and small tears around the bottom edges of the sheet were common. The high acid content of the substrate has left the newspaper extremely volatile. Based on some of the passages that I was able to decipher, this newspaper seems to fall into the historical trend of satire in trench newspapers, used as a means to cope among soldiers while disseminating information. The frequent incorporation of satire into trench newspapers is further discussed later in this article.

La Premiere Ligne

This second sample from the Kislak Center is remarkably for its simplicity, illustrating lower-cost techniques to produce short-run trench newspapers. Only two editions of La Premiere Ligne are housed by the Kislak Center at the University of Pennsylvania. The December 1916 edition is printed on the recto and verso of a single, thick, woven, 8.5 by 11-inch sheet of paper, the stencil for which appears to be made entirely with a typewriter. The newspaper is pure text of a uniform font and size, confirming it to be a reproduction of carbon-copied typed master. The newspaper is printed in faded, purple ink, suggesting strongly that hectography was used for its production (Van Dijck). The limited print run of La Premiere Ligne corroborates the use of hectography, which is limited to optimistically producing just a few dozen copies of a master document (Van Dijck). The edition is remarkable intact, with little wear or alterations on the paper besides a pencil marking used to correct the year in the top right corner of the recto. The substrate is not folded but appears to have experienced significant discoloration. There is clear yellowing in a uniform pattern along the edges of the newspaper, suggesting that this newspaper was previously stored in a stack and exposed to the sun. This newspaper is much more purely informational than other trench newspapers printed by the French army.

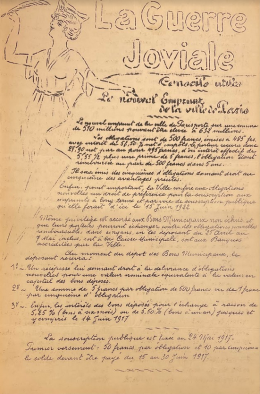

La Guerre Joviale

La Guerre Joviale is a standalone French trench newspaper housed by the Kislak Center. Like Le Dernier Bateau, the text and illustrations of the newspaper appear to be done by hand and copied onto machined paper, but the substrate itself is of higher quality. The paper is very smooth and thick, showing few signs of wear, aside from natural yellowing and small tears near the corners of the page. Examining the layout, this newspaper consists of a single bifolio and a nested folio inside the fold, for a total of 6 pages. The back page of the nested folio is blank. The newspaper shows some signs of being creased to form a small square, suggesting that it was folded several times for increased portability in transit or readership. The inkwork suggests that La Guerre Joviale was reproduced using a stencil and a mimeograph. The darkness and fullness of the text vary across the newspaper, with some sections of text appearing faint and pebbly and others appearing “blobby.” These features are characteristic of a mimeograph to which uneven pressure was applied, or for which the stencil was not perforated enough to allow an even flow of ink. This newspaper may have been produced using a hectograph, although highly unlikely given the variant ink patterns and the ink’s black color.

Historical Significance

Trench Newspapers as a News Source

Due to widespread censorship by the national governments of many Allied powers during the First World War [1], trench newspapers became an outlet for honest reports of the occurrences of war. While many trench newspapers were produced by conscripted soldiers for a soldier readership base, many trench newspapers served as a news source for the broader national community, including civilians (Van Dijck). At the same time, trench newspapers transmitted information to soldiers news from their hometowns. For this reason, trench newspapers stand uniquely at the intersection of civilian and military life and provide a unique window into the historical events of the period.

Unique Wartime Perspectives, Coping Mechanism

Trench newspapers frequently incorporated satirical multi-panel cartoons and passages humorously depicting interactions between soldiers across and behind enemy lines. Academics like Chapman suggest that satirical cartoons from World War I trench newspapers can be used to extrapolate the “bottom-up” perspectives of British and Canadian troops in the trenches. Indeed, the same applications are readily applicable to newspapers produced by the French army. Trench newspapers, including those produced by the French, encouraged collective identity and allowed soldiers to “survive the war” with humor (Chapman). Given the harsh reality of trench warfare, soldiers frequently turned to distractions like satirical journals to ease the tension and forget about the tragedy that surrounded them. In many ways, trench newspapers for soldiers were as much a means of coping with war as a new source.

Across Enemy Lines

Although this article focused primarily on French trench newspapers, the greatest volume of trench newspapers sources from the German Army [1]. German soldiers published millions of newspapers, distributed on the Eastern and Western fronts. German newspapers were frequently published more professionally on account of ease of access to printing technologies in Germany but historically approached content differently than Allied armies. According to some scholarship, German trench newspapers were “obsessed with justification” [1], providing explanations to the ranks of why the war was being fought. This is just one example of the collective national psyche that trench newspapers incidentally captured.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 Nelson, Robert L. “Soldier Newspapers: A Useful Source in the Social and Cultural History of the First World War and Beyond.” War in History 17, no. 2 (2010): 167–91. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26069867.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Hawley, Haven. 2014. "Revaluing Mimeographs as Historical Sources." RBM : A Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, and Cultural Heritage 15 (1): 40-55.