How to Know the Wild Flowers

Introduction

How to Know the Wild Flowers: a Guide to the Names, Haunts, and Habits of our Common Wild Flowers by Mrs. William Starr Dana (illustrated by Marion Satterlee and Elsie Louise Shaw) (1893) was published by Charles Scribner's Sons in New York, NY. The Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts at the University of Pennsylvania obtained a copy of the 1903 reprint edition as part of the Fritz Blank Culinary Archive and Library in 2008. Widely considered the first field guide to flowers issued in America, its publication marked an important moment in the establishment of the genre and the study of natural history in the United States more broadly.[1]

Historical Context

Frances Theodora Parsons

After the death of her husband, William Starr Dana, Frances Theodora Parsons embraced Victorian customs for widows, including the adoption of his name.[2] She also assumed an essentially solitary lifestyle, until her friend Marion Satterlee persuaded her to resume taking walks in the countryside. [2] She then rediscovered the love for botany that she developed while spending her childhood summers away from New York City in Newburgh, New York.[2] Together, the women collected the material for this hugely successful book.[2] Parsons went on to write a column about nature for the New York Tribune (compiled in her 1894 publication According to Season), as well as the successive guide How to Know the Ferns (1899), and a children’s handbook called Plants and Their Children (1896). She gave up naturalist writing when she became very active in the suffrage movement, though she also published a memoir entitled Perchance Some Day (1951) just before her death. [2]

19th-Century Women's Botanical Writings

How to Know the Wild Flowers played a significant role in the American “back-to-nature” movement, led by those concerned about the loss of wilderness with the rise of industrialization and urbanization between 1890 and the early 1920s.[3] Increasing participation in this movement around the country contributed to a more positive attitude towards nature than that which prevailed through much of the 19th century. [3] This led to a rise in “popular botany,” or the study of plants by nonspecialists. [3] Collecting and writing about plants became an especially prominent leisure activity for upper-class women primarily confined to the domestic sphere. [3] Though this began with the rise of the personal “nature essay,” by the turn of the century, field guides by women (especially in the Northeast) were becoming popular too.[3]

As opposed to earlier reference books that described species in technical, scientific language (most notably Asa Gray’s Manual of Botany, which Parsons herself referenced as an alternative model), How to Know the Wild Flowers allowed users with no outside knowledge to identify plants based only on their observations in the field. She cites the following quote, which she came across in a magazine article by celebrated naturalist John Burroughs, as her primary source of inspiration for the work:

- “One of these days someone will give us a hand-book of our flowers, by the aid of which we shall all be able to name those we gather on our walks without the trouble of analyzing them. In this book we shall have a list of all our flowers arranged accordingto color, as white flowers, blue flowers, yellow flowers, red flowers, etc. with the place of growth and the time of blooming.”

These words were so influential to her development of the book’s form that the entire page following the table of contents is allocated to them. With this dedication, she indirectly presents authorship as a collaborative process in which writers build upon the ideas of those before them. Burrough and Parsons must not have been alone in this interest, as the 1893 printing of the book sold out in five days.[4] It went on to receive great praise from figures as prominent as President Theodore Roosevelt and knowledgeable as botanist Frederick H. Knowlton, who wrote in an 1899 review that it had already “undoubtedly done more than any recent book to popularize this delightful branch of natural history."[3]

Textual Analysis

Paratexts

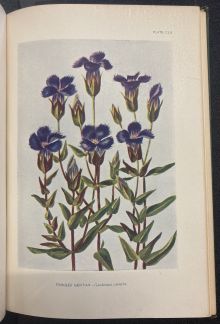

This edition of the book includes two prefaces: “Preface to the New Edition” and “Preface to the Old Edition.” The original section explores Parson’s interest in amateur botany and the development of an accessible guide that differentiates itself from those “keys which positively brushes with technical terms and outlandish titles.”[5] The second focuses entirely on revisions made to the text, including the selection of images and addition of species she since found to fit the criteria outlined in the following section, “How to Use This Book.” These include, most importantly, that flowers are neither unreasonably common nor impractically rare. The extent to which readers are likely to find them beautiful or interesting does not only determine whether they will be included but also how much space and attention they will be given. Justifying her decision regarding the book's length in this section, Parsons explains that it was designed to be “easily carried in the woods and the field.”[5] On the subject of its organizational structure (as proposed by Burroughs), she describes imagining her readers returning from nature walks with flowers to be sorted by color and then identified within each successive section. Finally, she lists the physical materials a reader will find useful throughout this process (a magnifying glass for viewing, a sharp pen knife and needles for dissecting, and a journal for notes) and recommends those expecting a more technical guide turn to Gray’s work instead.

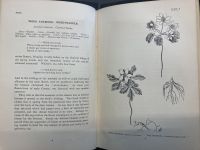

A numbered list of plates identified by the English and the scientific names of their corresponding species follows before the introductory chapter begins. This introduction provides a very brief history of botanical knowledge, including the findings of Carl Linnaeus and Charles Darwin. Parsons then gives a brief lesson on plant biology, outlining a flower’s parts and reproductive systems. A basic glossary of key vocabulary follows in the “Explanation of Terms” section. The list of “Notable Plant Families” and their visible identifiers is the last user feature preceding the body text.

More thorough reference features come after the “Flower Description” chapters, including three separate indexes. The “Index to Latin Names,” “Index to English Names,” and “Index to Technical Terms” each serve as extensions of front paratexts, especially the “List of Plates” and “Glossary.” They also serve as further evidence that Parsons intended the book to be used by a broad audience, including those with and without knowledge of scientific terminology. The book's final section exhibits six full-page publishers’ advertisements for books produced by Charles Scribner’s Sons. The company must have chosen these titles on account of a naturalist audience’s likely interest in them, which is why it is curious that one of these advertisements is for this same edition of How to Know the Wild Flowers. Others are for Parson’s own How to Know the Ferns and According to Season, as well as three books by American author and wildlife artist Ernest Thompson Seton, each featuring excerpted text and quotes from positive reviews.

Body Text

Imagery

Material Analysis

Substrate

Marginalia

Insertions

Readership

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 “How to Know the Wild Flowers: A Guide to the Names, Haunts and Habits of Our Common Wild Flowers.” Drawings and Prints, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/405911.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Anderson, Lorraine. Sisters of the Earth: Women's Prose and Poetry about Nature. Vintage Books, 2003.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Fitzpatrick, John Thomas. “Cultivating and Preserving American Wild Flowers, 1890–1965.” Cornell University, 2006.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Raymo, Chet. The Path: A One-Mile Walk through the Universe. Walker & Company, 2003.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Parsons, Frances Theodora. How to Know the Wild Flowers: A Guide to the Name, Haunts, and Habits of Our Common Wild Flowers. Charles Scribner's Sons, 1903.

- ↑ Stauffer, Andrew. Book Traces: Nineteenth-Century Readers and the Future of the Library. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021.

- ↑ Report of the Proceedings of the Twenty-Sixth Meeting of the Convention of American Instructors of the Deaf. United States Government Printing Office, 1929.