Alchemical Miscellany

Alchemical Miscellany is a medieval manuscript believed to have been published in the early 15th century in England. It is housed in the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts at the University of Pennsylvania, where it was acquired in 1922. The manuscript is a collection of earlier texts on alchemy that were combined and written in Latin.

Historical Context

Medieval Manuscripts

Medieval manuscripts such as this one were handwritten by scribes, usually monks in monasteries. This highly demanding labor required the scribe to copy texts onto a new substrate using narrow ruling lines to ensure the greatest quality. Most manuscripts were produced in monasteries because monks committed much of their life to this monotonous, yet difficult task. Because of this, Alchemical Miscellany is believed to have been made in this way, compiled by an unknown scribe.

Manuscripts in the medieval period were seen as something beyond the material content they contained, but rather as vehicles for ideas and thought.[1] Reading during this time period was very intensive: texts were studied with immense detail so every piece of knowledge was extracted from them.

Authorship

Because manuscripts during this time period were seen as platforms for the knowledge they contained, authorship did not exist in the way it does today. The title of this manuscript, Alchemical Miscellany, has significant meaning. ‘Miscellany’ refers to a specific category of medieval manuscript: a multi-textual manuscript - that is to say a collection of several works by various authors compiled by a single scribe.[2]

Alchemical Miscellany is one of these. It is a collection of four works on alchemy written by Roger Bacon, an experimental scientist who lived in the 13th century; Morienus, a 12th century alchemist; Geber, an unknown alchemist and scientist who lived in the 14th century; and Avicenna, an 11th century polymath who was regarded to be one of the smartest men of his time. The writers of the many sections of this miscellany span centuries and continents, and yet a scribe in England took their separate works and combined them to form a sort of journal that could be used to help advance scholarship in the field of alchemy, which was advancing rapidly during this time. [3]

The knowledge contained within these various component texts was seen as something worth compiling, yet seemingly no note was made on the authors in the original text. This speaks to how manuscripts were defined by their content, not their context or authors during this time period. To the scribe combining these texts, it was not relevant who wrote them, or when they were written, what mattered was the information they contained.[1]

Material Analysis

Organization

While some standard features of page organization from this time period are present, such as catch phrases to make sure pages are ordered correctly, this manuscript also contains some interesting organizational and navigational features.

Page Numbering

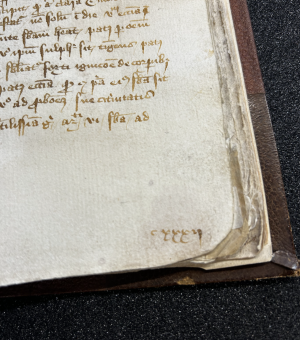

One unique feature of this manuscript is the presence of page numbers. In the bottom right corner of the recto on most pages is a series of roman numerals. Across pages, they increase in a steady manner. These numbers align with the actual number of pages in the text as assigned by later edits in the text as well.

The presence of pagination in such an early manuscript is very unique. A fascinating component of this is that this page numbering does not seem to be only for the scribe, but rather the reader. Because the pages are numbered on all the leaves, not just half as would be needed to help the scribe organize the writing, the numbers are most likely for a reader to use.

The handwriting, organization and placement of these page numbers also are very consistent, and analyzing them seems to imply they were placed after the text was written, at least some of them.

Index

The final section of this manuscript is an index to the texts. This is a very early example of an index: while they did exist prior to this manuscript, they were very rare. The index is on a page that is badly damaged, so it is impossible to see the entire content of the page, however it is definitely possible that the index contains references to the page numbers that are distributed throughout the text.

This index was most likely added by the scribe that produced the miscellany. It was added as a way to understand the structure of the manuscript and the contents within. This illustrates how the content of this manuscript was highly important over the substrate: the index does not seem to refer to the different authors or sections within the text, but rather highlights the content itself and the various topics covered within.

Substrate

Paper

Alchemical Miscellany is written on paper. This can be identified by the chain lines on the pages. Additionally, watermarks are present in the pages, but are hidden due to the binding. It is bound as a folio to a modern binding, with some sheets of more recent paper on the ends. This is an early example of a paper manuscript in Europe, but there are many examples of earlier paper texts.

Page Repair

An interesting feature of the paper in this manuscript is how it was treated. There are several examples of areas where the paper was damaged and then repaired by patching in new pieces. This was most likely done several centuries after the manuscript was originally produced.

Additionally, many of the corners are cut to rounds. The exact reason for this is unknown. It could have been done due to damage to the corners of the pages, to stop the spread of damage on the pages, or simply for aesthetic reasons.

Book Use

Marginalia and Asemic Marks

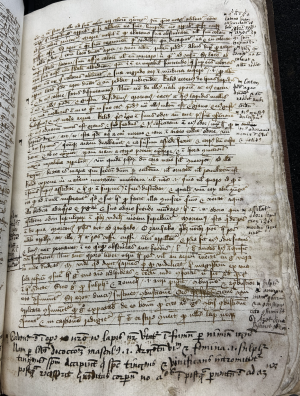

One of the most fascinating features of this manuscript is the incredible amounts of markings made in the text by readers. The medieval period was a time of intensive reading, not extensive reading like today.[1] This meant books were treasured for their content: instead of being read once and then moving on to another, books and manuscripts were gone over countless times and the information they contained was understood completely and exhaustively.

Some pages in this manuscript are covered in various marginalia - notes in the margins - as well as asemic markings - flags, underlinings, manicules - that serve to identify important parts of the text. These markings seem to be ‘clustered’ around certain areas of the text. Due to the scientific nature of this text, that might be because those areas are the most confusing and important to understand. This speaks to the use of this book as a scholarly resource.[4]

Medieval Scholarship

Scholarship was expanding dramatically during the medieval period. During this time, earlier works on science, such as alchemy, were copied and reworked. This allowed for research done over the course of the previous centuries to be distributed broadly, helping catalyze an acceleration in the development of science.[3]

That is the context in which Alchemical Miscellany fits: a collection of previous texts intended to be used by scholars. The high density of marginalia and various asemic marks speak to this use as an academic research: annotating difficult parts of text is a cornerstone of learning, especially in the sciences. This also is critical to understanding why many of these markings and notes are concentrated in specific areas of the text: the academics using this text found a few choice sections to have the most important knowledge. [4] This makes a lot of sense as well: often only some aspects of previous research have the most essential information from the entire text.

This manuscript was likely used to help scholars learn about the history of alchemy and to help guide their own studies in the topic. Because this text contained a summary of some of the most important research done by many of the most well known scholars of the previous centuries, it was a powerful resource for this new generation of scholars that were emerging in medieval Europe.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Michael Johnston, Daniel Wakelin. Immaterial Texts in Late Medieval England: Making English Literary Manuscripts, 1400–1500, The Review of English Studies, 2023.

- ↑ Corbellini, Sabrina, Giovanna Murano, and Giacomo Signore. Collecting, Organizing and Transmitting Knowledge : Miscellanies In Late Medieval Europe. Turnhout: Brepols, 2018.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Rampling, Jennifer M. The Experimental Fire : Inventing English Alchemy, 1300-1700. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2020.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Elizabeth Yale. Marginalia, commonplaces, and correspondence: Scribal exchange in early modern science, Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences, Volume 42, Issue 2, 2011, Pages 193-202.