Every Man His Own Physician

Overview

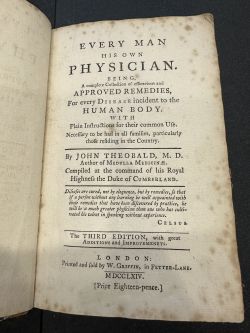

Written by English physician John Theobald, M.D. and published in 1764, Every Man His Own Physician is a popular 18th-Century medical recipe book. It’s subtitle is: Being, A Complete Collection of Efficacious and Approved Remedies, for Every Disease Incident to the Human Body. With Plain Instructions for their Common Use. Necessary to Be Had in All Families, Particularly Those Residing in the Country. It was likely used as a substitute for the opinion of a physician, surgeon, or apothecary in England, and it contains an exhaustive list of remedies for various ailments. This is its third edition so it was likely very popular and well-respected. This specific copy of Every Man His Own Physician is notable for its unique binding, pins, and extensive annotations from various hands. It is housed in the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts at the University of Pennsylvania. The book has presumably been owned by at least four different people as there are many notes and additional pages of notes inserted that have different handwriting styles. It is unknown who owned it. There is no clear evidence as to when the University of Pennsylvania acquired this book.

Historical Context

Medicine in 18th-Century England

In the mid-18th Century, England was developing its medical prowess, awareness, and education. Generational knowledge of disease outbreaks, infections, and treatment was critical in these advancements. Past epidemics like the Black Death and the Great Plague of London had decimated a significant portion of the English population in the 14th and 17th Centuries, respectively. [1] While these events were detrimental to the lives of millions of Europeans, they also taught the surviving populations important information regarding the spread of infectious disease and its treatment.[1] Contagion theory, the belief that some diseases could be transmitted from person to person by contact, was gaining in popularity and acceptance in the early 18th Century, yet physicians could not reach a consensus.[1] Germ theory would not be widely accepted until the 19th Century. [2]

Additionally, organized medicine was still in development. Hospitals existed throughout England but small towns often had less access to them. [3] Instead, many small English towns and cities were serviced by privately practicing, often uncertified surgeons. [3] Medical schools provided a rich liberal arts education and a wealth of medical knowledge to physicians but they were expensive. [3] Uncertified surgery was a profession that was often passed through a family, and the entirety of a surgeon’s education often came from their parent’s instruction.[3] These surgeons’ services were less expensive than trained physicians’ but their education and services were not as exceptional; many small towns still did not have access to many surgeons. [3] Thus, small towns in 18th-century England had relatively poor medical treatment and relied on familial practices and remedies.[4] People in large cities like London enjoyed increased access to hospitals, physicians, and surgeons. [3]

History of Medical Recipe Books

Recipe books were heavily influenced by women and their role in domesticity.[4] From a traditional and Western perspective, for a large part of history, women acted as housekeepers and thus made great strides to organize culinary, cleaning, and medical household information.[4] Specifically, women often created “recipe” books for common ailments, wounds, or pains that outlined various remedies and steps to cure one of their afflictions.[4] These household medical recipe books could then be passed down through generations and edited to create a more complete compilation of remedies.[4]

Published medical recipe books capitalized on the general public’s contemporary inclination to self-diagnose, the rise of consumerism, and the convenience of having a wealth of knowledge in one’s own home library.[5] These books contained recipes for many different types of ailments, from simple colds to more obscure afflictions like a dog bite.[5] They also present immense variety in the different ingredients necessary to complete the recipe, namely natural remedies that are not commonplace in medicine today.[5] It is highly likely that mass-produced medical recipe books were marketed toward the rural and small-town populations who relied on natural remedies and did not have immediate access to medical care.

Understanding Every Man His Own Physician

Publishing Information

Examining the title page, one can discern several important pieces of information about Every Man His Own Physician. Firstly, this book was published in 1764. At the bottom of the page, the Roman numerals “MDCCLXIV” are listed; this translates to 1764. The book also seems to have been published in London, England, as denoted by “L O N D O N” running across the bottom of the page. The book was published by W. Griffin. It is said to have been printed in "Fetter-Lane,” which is a street in London. There isn’t any clear evidence that this book is copyrighted. However, under the author’s name on the title page, the following statement is printed: “Compiled at the command of his Royal Highness the Duke of CUMBERLAND.” It is likely that the Duke of Cumberland commissioned the printing of this book and thus it is “licensed” by him.

Substrate, Format, and Platform

This book resembles a modern codex. Its bibliographic format is quarto style. The signatures “B” and “B2” are followed by two blank pages and are then followed up by “C” and “C2.” Since the groupings are organized into four sheets and the book is relatively small, it must be a quarto. The pages are about six inches by nine inches and there are multiple groupings that make up the entire book.

The book seems to be made of paper. The paper has a rough, uneven surface, the pages are somewhat thick, there are many stains along the perimeter of the pages (likely due to water), many pages have small holes, and the pages are tan.

Binding

The object is bound with a wooden headpiece and it is likely the original binding from 1764. Both the front and back covers have a greenish-blue, wavy design on the outside of the wood that could have been painted on. The spine is brown and has five hubs running down the side.

The front cover is completely separated from the spine. Both the front and back covers have some of the original design of the wood chipped away and the actual wood fibers have been revealed at the corners of the covers. It is notable that a blank page was interleaved in between each printed page, meaning that page 1 appears on the recto side of a page, 2 on verso, and then the following recto page is an unprinted page. Also, the index comes before the first page of content even though its page numbers are listed as 50 and 51. This may have been a mistake in the binding. The interleaved unprinted pages and the misplaced index may serve as evidence that an owner of the book purchased it unbound, collected blank pages to interleave in between the intended sequence of pages, and put the index before page 1.

The book’s index, which comes right before the content of the book begins, as well as page numbers, which run along the upper right-hand corner of recto pages and the upper left-hand corner of the verso pages, contribute to the book’s navigation system. The numbers run from 2 to 48. It is also of note that the second and third pages of the index have the numbers 50 and 51 respectively. The page number of the first page of the appendix, 41, is printed in the middle of the page and is listed as “(41).” This system of page numbers along with an index that identifies the diseases mentioned on each page creates an accessible method for finding the remedy to an ailment quickly. The reader of this book is likely looking for an immediate solution to a potentially urgent, even life-threatening problem. The index and page number system anticipates this type of reader and thus allows easy navigation through the book’s contents.

Paratexts

After the title page, the book has two prefaces. The first is the preface to the original book and the second is the preface to the second edition. This is the third edition of the book. The prefaces essentially describe the purpose of the books, which is to provide medical remedies for ailments when one is unable to see a physician, and they also inform the reader that these are not actual cures to their diseases; they are not going to extinguish a disease but will reduce its effects. The first preface has the text “J. THEOBALD” at the end of the passage, indicating that J. Theobald, the author of the book, wrote it. Then, the second preface has the text “THE EDITOR” at the end of the passage, indicating that the editor of the second edition wrote it.

The index also provides a table of contents for each of the diseases and ailments mentioned in the book. There is no indication as to who wrote the index so I am led to believe J. Theobald, the author, wrote it. Finally, there is an appendix at the end of the book that explains how to make some of the medicines and remedies mentioned in the book. There is no indication as to who wrote the index so I am led to believe J. Theobald, the author, wrote it.

Physical Manipulation, Annotations, and Book Use

There are countless annotations throughout the entire book. The front and back pastedowns and blank flyleaves are completely written over. It seems that there has been a blank page inserted in between every printed page and each of those pages has more writing/annotations. There are also additional pages and small notes pinned into the pages. Intimate interaction with a book in such a manner is often reflective of typical 18th Century practices in the wake of the mass production of books.[6] In an era where people had unprecedented access to new books and information, people often felt more drawn to writing and physically modifying books to slowly process the information.[6]

The annotations generally seem to be additional medical recipes that aren’t already found in the book. It is unclear who wrote these annotations; but since they are all medical recipes, it is possible that a physician is writing their own cures into the book. It could also be possible that this was a book passed down through families and different people recorded their own remedies in the book. Based on the different types of handwriting, it is likely that multiple people have written in this book. If physicians owned this, they may have used the book as a guide and added their own recipes so that they had a complete guide to their medicine. If a family owned this, they may have kept their recipes in the book so that they can be easily accessed if someone is sick.

The following is a transcription of the text of one of the annotations. It is written on an unprinted page between pages “2” and “3.” It reads:

Ague Take 2 ounces of best Jesuits Bark Cream of Tartar as much as will lay on a Shilling mix them in two bottles of red Wine let the patient take one wine Glass tasting in the morning one at noon and one the last thing before going to Bed mix the Powders in one Bottle & then pour off when fine and fill the same bottle up again with the other Quart

This annotation directly relates to the book’s section on “Ague,” which is an archaic term for a fever or general sickness. While the book informs the reader to cause the afflicted person to vomit, use powdered Peruvian bark and several other ingredients, and take it with red wine, the annotation makes slight adjustments to the recipe. Above and below this annotation are other recipes that are apparently meant to subdue ague.

It is notable that there are no edits or markings on the book’s entries for ague. Throughout the book, there is not much evidence of direct interaction with the text. Essentially all of the annotations and marks were additional remedies written on adjacent, blank pages; never on the printed page. However, occasionally, there is a small “X” drawn next to some recipes. This may have served to inform readers or the annotator themselves that the marked recipe is not to be used. The annotator may have also potentially written their own recipe for the ailment that they want to use instead. Other than this, there really aren’t any other marks. The reader may have really respected the authority of the author and didn’t want to edit or write over the remedies.

This information, combined with the fact that the book was likely assembled so that the owner could take notes on blank pages interleaved throughout the printed pages, studies of the pinned pages and physical modifications to the book, the many annotations, the many handwritings, and the content of the transcribed annotation support the notion that this book was passed through the hands of several physicians. The first owner was likely a physician who wanted a copy of the book to study and add to in order to create a compilation of all their knowledge of medical remedies. The book may have been specifically bound with blank pages so that the owner could write their own cures. When more space was needed for more remedies, the owner likely wrote new remedies on a loose piece of paper and then either pinned it or placed it in the book. The owner would likely read the entries in the book and then write their own recipes for the ailment next to or as close to the entry as possible. Then, based on the fact that there are multiple sets of handwriting, the original owner may have passed the book down to another physician who then also made edits. It is also possible that the book was a project between multiple physicians at the same time who wanted to create a compilation of all their combined medical knowledge.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Zuckerman, Arnold. “Plague and Contagionism in Eighteenth-Century England: The Role of Richard Mead.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine, Vol. 78, no. 2, 2004, pp. 273-308, https://www.jstor.org/stable/44448005. Accessed 22 April 2023.

- ↑ Britannica.com. Verification of the germ theory. [online] Available at: <https://www.britannica.com/science/history-of-medicine/Verification-of-the-germ-theory> [Accessed 22 April 2023].

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Brown, Michael. “The Doctors Club: politeness, sociability and the culture of medico-gentility.” Performing Medicine. Manchester University Press, 2011, pp. 13-47, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt21216ph.7. Accessed 22 April 2023.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Matei, Oana. “Recipes and thrift in early modern and modern knowledge.” Centaurus, 2021, pp. 416-420, https://doi.org/10.1111/1600-0498.12331. Accessed 22 April 2023.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Osborn, Sally A. “The Role of Domestic Knowledge in an Era of Professionalisation: Eighteenth-Century Manuscript Medical Recipe Collections.” University of Roehampton, 2015, https://pure.roehampton.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/422029/Sally_Osborn_thesis.pdf. Accessed 22 Apri 2023.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Rosenberg, Daniel. “Early Modern Information Overload.” Journal of the History of Ideas, vol. 64, no. 1, 2003, pp. 1-9, doi:10.1353/jhi.2003.0017.