John B. Thayer Titanic Memorial Collection

The John B. Thayer memorial collection of the Sinking of the Titanic is an archive of first-hand accounts, family material, and memorialization efforts kept by the prominent, Philadelphia-based Thayer family from 1912 to 2012. The collection was started in memory of John Borland Thayer II (Sr.) who died during the sinking of the ocean liner’s maiden voyage.

Thayer’s wife, Marian Longstreth Morris Thayer, and son, John “Jack” Borland Thayer III (Jr.), survived the tragedy and created the collection. In 2014, the collection was gifted to the University of Pennsylvania's Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts by Jack Thayer's daughter, Pauline Thayer Maguire, and her husband, Robert Maguire.

History

The Thayers were a prominent and wealthy family in the Philadelphia area at the turn of the 19th century. John Borland Thayer Sr. (1862-1912) was born in Philadelphia and attended the University of Pennsylvania. He was the Second Vice President of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company at the time of his death. He lived in Haverford, Pennsylvania with his wife, Marian Thayer, (1872-1944) and their four children: John “Jack” Borland Thayer Jr. (1894-1945), Frederick Morris Thayer (1896-1956), Margaret Thayer (1898-1960), and Pauline Thayer (1901-1981). In 1912, John, Marion, and Jack traveled to Europe and boarded the RMS Titanic for their return to the United States.

On the night of April 14, 1912, the Titanic disaster began. Separated from her husband and son by a large crowd, Marian boarded lifeboat 4. As the ship began to sink, 17-year-old Jack stood by the rail with passenger Milton Long, who he’d just met, said goodbye, and jumped feet first just before it split in half. He was pulled underwater by the suction of the sinking vessel, but found refuge on an overturned lifeboat and was eventually rescued by lifeboat 12. He was reunited with his mother on the RMS Carpathia. His father's body was never recovered. [1]

Four years later, Jack graduated from the University of Pennsylvania, served as a captain in the United States Army in World War I, and began his career in banking. He married Lois Buchanan Cassatt in 1917 and had six children: Edward and John (who both enlisted in the armed forces during World War II), Lois, Julie, Pauline, and Alexander, who died a few days after his birth. Jack served as treasurer and, later, financial vice-president for the University of Pennsylvania from 1939 until his death by suicide in 1945 at the age of 50. Contributions to the depression Jack suffered from later in life were the deaths of his son, Edward, and mother, Marian. A bomber pilot during the war, Edward’s plane was shot down in 1943 and his body was never found. Marion died at her home in Haverford on April 14, 1944, the 32nd anniversary of the Titanic disaster, at the age of 72.

As a reader and researcher of the Thayer family’s history and memorial collection, I have adopted Astrid Rasch’s proposed strategy of anxious reading that subjects texts, specifically memoirs, to “critical scrutiny despite, and alongside, the empathy that we feel for our subjects…This entails acknowledging both the pain that the author has gone through and the traumatic experience of those represented, and at the same time examining the way in which that trauma is described and how it functions in the moral and political economy of the text in its context [2](Rasch 5). This subscription to anxious reading has allowed me to sympathetically engage with this memorial collection and the Thayer family who, as victims of a random and cruel trauma, have continued to bear witness to extreme suffering, grief, and loss since 1912. As Jack recalls in an article for the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin in 1932, "the spectacle of nearly 1,500 people struggling in the ice-cold waters of the Atlantic, and the steady roar of their voices, which kept up for 15 or 20 minutes, is a memory that does not become dim, even after 20 years" [3] Alongside this sympathetic reading is a critical examination of the Thayer family’s socioeconomic positions at the time of the sinking and beyond. As white Americans, aristocrats, and first-class survivors with ties to powerful institutions in the Philadelphia area, the Thayers had access to the technology, capital, and publishing resources that allowed for the creation, protection, and century-long maintenance of this extensive and historically valuable collection. Instead of ignoring the traumatic impact of the violence of the Titanic disaster on the Thayer family, I aim to follow Rasch and use this impact as a “point of departure that allows us to study not violence itself, but our own empathetic response to the traumatized victim, and to ask how such a response focuses our attention on some victims over others." Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag

-

Columbus Dispatch - April 21, 1912

-

New York City World - April 21, 1912

-

Baltimore Sun - April 21, 1912

-

Davenport Democrat & Sioux City Journal - April 21-24, 1912

-

Titusville Herald - April 24, 1912

-

Memphis Commercial Appeal & Nashville Tennessean - April 21, 1912

-

Washington Post - April 21, 1912

-

New York City Tribune - April 21, 1912

-

Newark Sunday Call - April 21, 1912

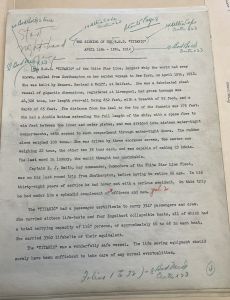

The Sinking of the S.S. Titanic, April 14-15, 1912

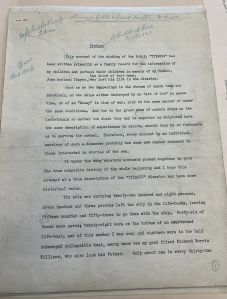

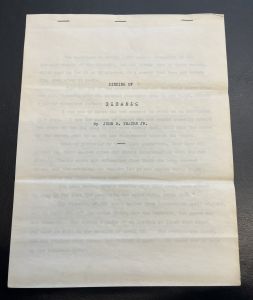

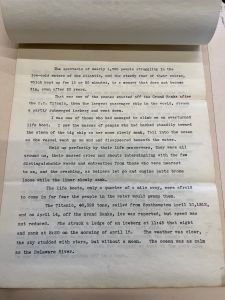

In Folders 6-9 are the various versions of Jack Thayer’s memoir, Sinking of the S.S. Titanic, including the original carbon typescript, original ribbon typescript, and galley proofs [1 clean and 1 corrected copy] that paved the way for its private publishing in 1940. Also in the folder is a Library of Congress certificate of copyright registration. In contrast to the wide reach achieved by Jack’s testimony to the press in 1912 (as seen in Folder 3), his revisitation of the tragedy 28 years later in the form of a memoir was "written primarily as a family record for the information of [his] children and perhaps their children in memory of [his] father, John Borland Thayer, the third of that name, who lost his life in the disaster," (The Sinking of the S.S. Titanic, box 1, folder 6).

The multiple preliminary versions and drafts of the memoir featured in these folders, as well as the significant amount of corrective marginalia, indicate that they were read, proofread, agonized over, and finally perfected to produce a thoughtful and literary organization of Jack’s intimate thoughts, feelings, and memories of the disaster and its aftermath. In one of the more gripping sections of the memoir, Jack “merges self and world in a metaphorical manner” and characterizes the Titanic disaster as the “20th century’s wake-up call”, ‘It seems to me that the disaster about to occur was the event, which not only made the world rub its eyes and awake, but woke it with a start, keeping it moving at a rapidly accelerating pace ever since, with less and less peace, satisfaction, and happiness.’ (518-19) As Peter Middleton and Tim Woods describe, “Disaster made him aware that the self is a ‘Being-towards-the end’...a self whose awareness of its own inevitable mortal ending helps constitute its sense of the world. (518-19)

In this instance of persistence and remembrance, we see a victim of tragedy become an agent and authority of his own history. The creation, organization, and perfection of Jack’s memoir was certainly a labor of love meant to inform his immediate family of his own experiences and perspective and honor his late father’s legacy. The memoir’s private publishing and copyright registration are suggestive of Jack's protective authorship and ownership of ideas and a desire for officiality and federal recognition. A closing sentence. Something about the capital needed, Penn publishing, etc.

-

Original ribbon typescript with proofreader's corrections

-

Preface with proofreader's corrections

-

Title page

-

First page

Letter regarding James Cameron's Titanic

In Folder 26 are two letters from Merie Weismiller Wallace, a Los Angeles-based unit still photographer, to Pauline Thayer Maguire and her husband, Robert regarding the production of James Cameron’s 1997 film Titanic. The first letter, dated August 5, 1996, is a printed word document from Wallace requesting access to a “steerage class servant account which was never published” and which the Maguires had a copy of. There are several instances of handwriting and annotation including Wallace’s signature at the end of the letter, a series of numbers, the phrase “James Cameron Titanic”, and the highlighting of Cameron’s name and a sentence establishing a response deadline from the Maguires which suggests that the letter was used as a reminder to respond. The second letter, dated September 17, is a note of appreciation, handwritten on a monogrammed card, from Wallace to Robert Maguire thanking him for providing access to the servant account, “Jim was pleased to read it, as it contained details which he perceived as speculation previously – such as the sound and water in steerage class.” Wallace also writes about how amazing the project is, “...to see ½ of the Titanic being built in an outdoor water tank is incredible. The interior sets are so opulent – as is the wardrobe.”

These letters are instances of remembrance and semi-historical accounts of the Titanic disaster that were made by people—in this case, filmmakers like Cameron and Wallace—who did not experience it. Middleton and Woods make a compelling argument for the renewed interest in the Titanic and its victims that spiked in the late 20th century and resulted in an expensive, widely popular, and romanticized retelling of the ship’s history, like Cameron’s 1997 major motion picture. They argue that footage of the recent 1985 discovery of the shipwreck (acquired by oceanographers Robert Ballard and Louis-Michel) coupled with cultural practices of memory, “especially oral recall, keepsakes, and photographs” [2] function in the Titanic film to “make the lost world of the ship’s history perceptible again.” [2] “The collaboration of the search technology and the survivor’s memory, focused on this site of memory, at last makes it possible to travel back in time with the camera and witness the whole of the final voyage and its immediate aftermath.” [2] We see this sentiment at work in Wallace’s letters to the Maguires. They exhibit Cameron’s desire to re-create a relatively authentic and accurate re-telling of the tragedy by drawing on and incorporating a servant’s first-hand account of the sinking and utilizing industry, technology, and artistry—better known as movie magic—in his remembrance project. [4]

Legacy

The John B. Thayer memorial collection of the Sinking of the Titanic is a moving tribute to those who lost their lives in the 1912 disaster, including John Thayer Sr. It is an intimate look into the Thayer family's selective acts of remembrance of the tragedy, their survival, and the many lives they led until 2012. It is also a fascinating and useful century-old historical body that documents the progression and evolution of social and cultural memory of trauma as it relates to the Titanic tragedy. Beginning with a newspaper scrapbook of Jack Thayer's 1912 survivor's testimony, the collection grows, as time passes, and manifests more official and authoritative efforts to memorialize the tragedy, including Jack’s privately published 1940 memoir and documentation of James Cameron’s efforts to authenticate his 1997 film by consulting Thayer family records. The study of the collection as a whole, but especially of these notable items, showcases how the Thayer family’s efforts to memorialize their patriarch, recount their trauma, and keep the Thayer legacy alive have evolved over time.

References

- ↑ John B. Thayer memorial collection of the Sinking of the Titanic, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania, box 1, folder 3.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Rasch, Astrid. "Anxious Reading: Interrogating Selective Empathy in Trauma Memoirs." Auto/biography Studies, 2021, p.5 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "multiple" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ John B. Thayer memorial collection of the Sinking of the Titanic, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania, box 1, folder 4

- ↑ Peter Middleton & Tim Woods. “Textual memory: The making of the Titanic's literary archive.” Textual Practice, 15:3, 2001, 507-526. DOI: 10.1080/09502360110070420